|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 11 mins

July 9, 2024

Happy Birthday, Slinger Francisco, aka Mighty Sparrow! Today, his 89th birthday, Big Drum Nation is proud to republish a slightly edited 2020 article by founding editor Caldwell Taylor–A Birthday Tribute in recognition of the bard’s 66th year on the stage.

– BDN Editors

“Calypso is a product of Caribbean people’s struggle to articulate an identity in response to numerous attempts at fragmentation.” – Carole Boyce-Davis

Long after most of us are forgotten, certain calypsoes will survive as the only reminders to some later generation of how we lived, loved, laboured and sinned. – Albert “Bertie” Gomes

“Would you like to know what is calypso?

It was sung by the Creoles years ago

It was danced by the African drums in a bamboo tent

And sung in patois for amusement

Now it is played in tone

On a gramophone” – Lord Executor

[Calypso] is a feeling which comes from deep within

A tale of joy or one of suffering

It is an editorial in song

Of the life that we undergo

That and only that, I know

Is true calypso – Mighty Duke (Kelvin Pope)

Sixty-six years ago the “Sparrow Revolution” was brilliantly sung into existence when “the Mighty Sparrow”, then rated a “B” calypsonian–seized the calypso crown and with it the commanding heights of calypsodom.

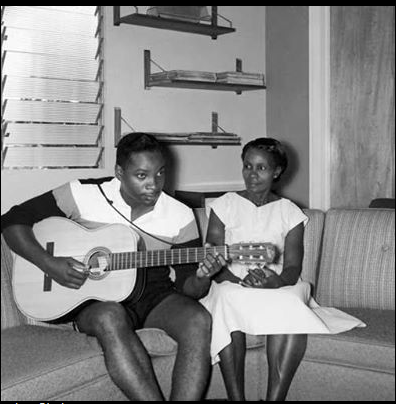

Sparrow and his mother, Clarissa Francisco

The “Laddie” was merely 20 years old and his “B” rating had to do with the fact that his calypso singing consisted mostly in “hustling tourists” in the “Gaza Strip” area of Port of Spain. But B rating or not, the Sparrow “takeover” of February 12, 1956, was no fluke, for fifty years later he remains the dominant figure in calypso-a truly astounding achievement in the quirky world of a “manifesto” named “Yankee Gone” ( renamed Jean and Dinah“), an infectious mix of sex, social commentary, Sparrowesque braggadocio, and creole nationalism: It retooled the calypso art form, giving it a new sound, a new style, a new sensibility, new stagecraft; it also introduced the human voice as a key aspect of calypso instrumentation.

The Sparrow Revolution also gave us the “new calypsonian”- Sparrow being the prototype- and it changed calypso’s two crucial constituencies, young people and women, and shortened the distance between “singer” and “audience”. The Revolution prefigured the coming of a new breed of politicians, “the so-called Black intellectuals” of the People’s National Movement (PNM), whose September 1956 victory put an end to the political careers of “Old Guardists” like Tubal Uriah “Buzz” Butler (1897-1977), Roy Joseph, and Albert “Bertie” Gomes. And Sparrow could claim to have had a hand in the PNM takeover, for in 1955 he became a member of “Gayap“, a group that worked for Eric Williams before the People’s Educational Movement (PEM) became the People’s National Movement in January 1956.

Eric Williams and Sparrow, the scholar and the songster, were quite fond of each other and there were in the early days many public displays of their mutual affection. Sparrow, at least until the mid-sixties, tolerated no opposition to Williams’s PNM he sang songs like ‘Leave The Dam Doctor’ and ‘William the Conqueror’:

Praise little Eric, rejoice and be glad

We had a better future here in Trinidad PNM

It ent got nobody like them

For they have a champion leader

William the Conqueror

‘Leave the Damn Doctor’ was Sparrow’s hard-hitting

response to Growling Tiger’s satirical stabs at Williams’s

moral armor; the “Tiger” chastized “the Doc” for deserting

his wife just hours following a secret wedding on Caledonia

island in 1957.

Tiger sang:

No, no, not the Doc

No, no, not the beloved Doctor

I can afford to gamble my life

He’ll never marry and next day desert his wife

Sparrow retorted:

Leave the damn Doctor

He ent trouble allyuh

Leave the Damn Doctor

What he do he well do

Leave the damn Doctor

And doh get me mad

Leave the damn doctor

Or is murder in Trinidad

SPARROW, WILLIAMS, AND THE FEDERATION

Sparrow was again on Williams’s side in the region-wide donnybrook that attended the mash-up of the West Indies Federation in 1962. Williams was of course at the center of this affair, for he was not only a ” key player” but also the principal spokesman for a highly centralized form of federation. The federation that Dr Williams envisaged is illustrated in a September 1959 document titled “ The Economics of Nationhood”; it was Trinidad and Tobago’s reply to the Jamaican Government’s Paper No. 18. In The Economics of Nationhood Dr. Williams and the PNM Government called for the creation of a Federation that was “adequately empowered at the center to shape and direct the future of the [West Indian] Nation!”

Williams’s vision of Federation was one that was ‘too centrally directed’ for the Jamaicans’ taste; they wanted an arrangement that gave the respective territorial units lots of room to maneuver, particularly in the area of economic development. After Bustamente (1884-1977), Edward Seaga and others in the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), Norman Manley (1893-1969), the Jamaican premier, made the decision to turn the matter over to the Jamaican voters in a referendum. The vote was held on 19 September 1961 – the 23rd anniversary of the launching of the Manley’s People’s National Party (PNP) in 1938. At the end of the day, the “No” side won, taking some 54 percent of the vote: a total of 38,942 votes separated the winners, Bustamante’s JLP, from Norman Manley’s PNP, the losers.

Jamaica’s decision to quit spelled the end of the West Indies Federation. Sensing that the moment was ripe for a West Indian-style speech performance, Williams summed up the situation in a manner that could make a battle-hardened “Midnight Robber” blush: “One from ten leaves naught“, he quipped. Sparrow soon followed with his own take on the break-up.

In a song called ‘Federation’, he sang:

Federation came down to simply this

is dog eat dog and the survival of the fittest

Everybody fighting for independence, singularly;

Trinidad for instance

But we go get too don’t bother

But ah find we should all be together

Not separated as we are

Because of Jamaica

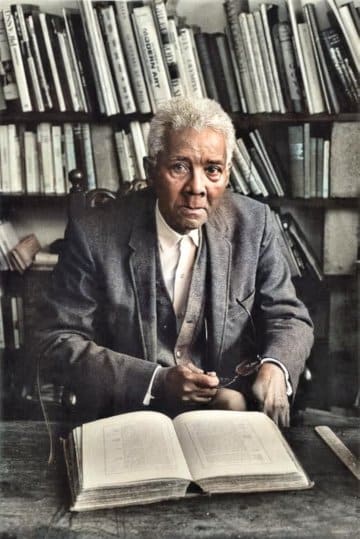

CLR James (1901-1989), the world-renowned Marxist theoretician (and a big Sparrow fan) was in the calypso tent that night when Sparrow sang ‘Federation’ for the very first time.

James commented:

I was in the tent the night he returned and first sang it. When it became clear what he was saying, the audience froze. Trinidad had broken with the Federation. Nobody was saying anything and the people did not know what to think, far less what to say. At the end of the last verse o that first night Sparrow say that something was wrong and he added loudly: “I agree with the Doctor” (James: Party Politics in the West Indies,p. 162).

And of course, the Doc agreed with the Sparrow. Being an astute politician Williams understood the value of Sparrow’s popular appeal and immense pedagogical powers. Indeed, he acknowledges this in his autobiography “Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (1969), where he writes that Sparrow was often the person

who “summed up public feeling”. Williams would return to Sparrow’s public leadership in a 1980 letter sent to the calypsonian on the happy occasion of his 25th anniversary in the calypso business.

In that same note, carried in the Trinidad Express newspaper on January 6, 1980, Williams allowed that Sparrow had come to his assistance with the song ‘Leave the Dam Doctor’.

But it must also be said that Williams’s grasp of the significance of the calypso predated the Sparrow phenomenon by many years. This fact can be gleaned from the comments made in “The Negro in The Caribbean“, a book that was published in 1942 when Williams was still an assistant professor of social and political science at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Dr. Williams wrote:

The major accomplishment in the field of native culture in the British islands is the calypso of Trinidad. The calypso is a popular song, spontaneously composed, with a refrain sung at the annual carnival. These songs, some vulgar and banal in the extreme, have become a vehicle for social philosophies, satirical quips on men, and matters of local and world importance. (p.80)

THE BIRTH OF THE SPARROW

Sparrow’s rise was not driven by good luck, nor by bard’s good looks and rare magnetism. Furthermore, his ascent to calypso fame and fortune did not begin in 1954, when he made his tent debut ( the Old Brigade) with a song called “The Parrot and the Monkey” and was “introduced” by master-of-ceremonies, “Viking“- in the following manner:

“Ladies and Gentleman

It have a lil feller here who say he could sing.

So I will bring him on stage to you.

If you think ‘e good, clap.

And you know what to do if ‘e ent good”

The ‘lil feller’ went right ahead and brought the tent down. According to calypso legend, the name “Sparrow” was conferred by a veteran calypsonian just after the lil feller exited the stage on that night back in 1954. But why “Sparrow”? Was it because the young bard’s stage mannerisms reminded the veteran of the nervous pecking of a bird? Or was it the exceptional quality of the young bard’s singing voice? The latter seemed the more probable and of course a lot more flattering. In any case, the story of the rise of the Sparrow begins in 1948, not 1954. That story bears telling. But first a brief detour.

TRINIDAD IN THE FORTIES

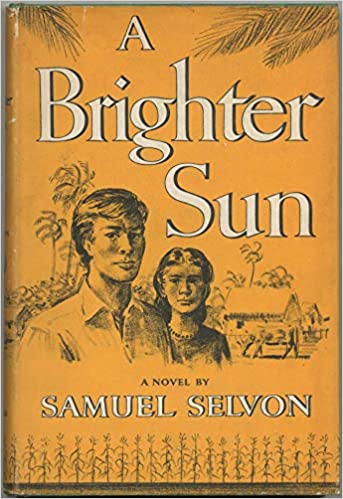

The 1940s saw the coming of the American naval-military bases. Trinidadians were deeply conflicted over the American presence which, on the one hand, was tearing apart the moral and social dollars in the local economy. Samuel Selvon (1924-1994 ) treats this matter in his first novel “A Brighter Sun” (1952) where he introduces us to “Joe” and “Tiger”, two men who benefited enormously from the American presence. The American “social invasion” drew comments (in song) from the redoubtable Attila the Hun (1892-1962).

Attila sang:

The Yankees launched a real social invasion

Thay did as they pleased in my native land

Thay had a lot of money and spent lavishly

And they broke down the pillars of our aristocracy

I must confess they help us financially

But played hell with our morality

They took all our girls and had a glorious time

And left us blue-eyed babies to mind.

“Lord Invader” (1914-1961) also commented on the moral erosion wrought by the American presence in a song called ‘Rum and Coca-Cola’ .A 1944 cover version of this song, done by an American girl group, the Andrews sisters, brought calypso into the American mainstream. The song sold 7 million copies even though it was banned by network radio because it mentioned an alcoholic beverage (rum): The U.S. Alcohol Prohibition law was repealed in 1933, but many Americans kept up a puritanical distaste for booze.

With the U.S. Bases came American-style racism, prostitution, the zoot-suited saga boy, and the razor-wielding badjohn who mimicked the gangsters in the American movies. These phenomena provoked cultural and political responses which helped to galvanize the campaigns for political and constitutional reform, leading to the introduction of universal adult suffrage in 1946; the Legislature got its first woman member, Audrey Jeffers (1898-1968), that very year. Ms. Jeffers was “the only women” to be seen in the calypso tent back in the 1950s, according to calypsonian “Lord Superior”.

The 1940s also saw the coming of the steelband and other expressions of a nascent cultural nationalism: the calypsonian was in the vanguard of these struggles to forge a Trinidadian consciousness. Truth be told, the calypsonian’s vanguard role goes as far back as 1805, when an anonymous bard composed lyrics to put spirit into the revolutionaries who planned to overthrow the Trinidadian slaveocracy a la Haiti.

“Cloaked in a blasphemous parody of the Catholic mass,” the song said”:

Pain nous ca mange

C’est viande beke

Di vin nous ca boue

C’est sang beke

He! St Domingo,

songe St Domingo

The bread we eat

Is the white man’s flesh

The wine we drink

is the white man’s blood

Hey! St Domingo,

Remember St. Domingo

In 1946, calypsonian Raymond Quevado (“Attila the Hun”) won a seat on the Port of Spain City Council. The bard was a leading member of the Trinidad Labour party, where he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Captain A.A. Cipriani, a hero of the Trinbago working class, Albert Gomes, Aubrey James, and the Grenadian-born McClean Pope. Attila fought relentlessly against the Theatres and Dance Hall Ordinance, a 1934 law that provided for police censorship and regulation of calypso and calypsonians. This repressive law was used in an attempt to silence the Growling Tiger in 1950 when the calypsonian sang “Daniel Must Go”, demanding the dismissal and deportation of Captain W.E. Daniel, the British Director of Education of Trinidad and Tobago. Attila, Manager of Tiger’s Victory Calypso Tent, was charged by the police pursuant to the provisions of the Theatres and Dance Hall law. Defended by ace lawyer Hugh Wooding, Attila got away on a legal technicality.

In 1946 ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax produced his “Calypso at Midnight” show at the Town Hall in New York, featuring “Macbeth the Great”, “Invader” and the “Duke of Iron” with musical accompaniment by Gerald Clark and his Serenaders.

And calypso went on the Broadway stage in 1947, in a show named “Caribbean Carnival” which was produced by Sam Manning and Adolph Thenstead.

In June 1948 Lord Kitchener (1922-2000) and his friend and fellow calypsonian Lord Beginner (1904 – 1980) were among the six hundred West Indians who rode the SS Empire Windrush to England. Significantly, Harold Phillips (1928-2000), the future Lord Woodbine, was also on the Windrush. The fare to the Mother Country was a mere #28 and it is said that

“Kitch” set foot on British soil while leading a chorus in the singing of ‘London is the Place for Me.’ In 1948 all of Trinidad sang Lord Melody’s “Canaan Barrow”; The ’48 Calypso King competition was won by “ Mighty Killer”, whose winning rendition was titled ‘East Indians With Christian Names’.

In the early 1940s Trinidad, with a population of just over 500,000, was largely a rural society, and its meager intellectual and cultural life was confined to the Port-of Spain area which had a population of just over one hundred thousand; Port-of Spain’s population actually grew by one half between 1931and 1942. In the early 1940s, the Trinidad Guardian was the country’s largest newspaper with a weekend-end circulation of just over 40,000, the overwhelming majority of subscribers. In 1948, Slinger Francisco (“Sparrow”) was a 13-year-old student at the Newtown Roman Catholic Boys School on Maraval Road.

Slinger was a member of the school’s choir, which promoted a modicum of musical literacy and vocal skills. In 1948, singing was the only mode of musical performance in the nearly 300 primary schools in Trinidad; it was a group activity and was based on the British 19th-century choral tradition.

Slinger loved to sing, something he took from his mother, Clarissa- and so he was a fixture in the school’s weekly concerts. Week after week the young man sang but it was always the same song:

“Red River Valley“. Though he was quite a popular kid, ‘One Song Slinger’ was getting on everybody’s nerves. Slinger soon realised this and so he decided to change his tune. It was a “regular” Friday, Concert Day, when Slinger walked up to “Teacher Carl” (Jagnauth) could answer, Slinger was on the stage singing a song by one of his early idols, Lord Invader (1914-1961). Slinger sang:

Before the landing of the Yankees

Everything I give me wife

She never displeased

A deafening hush fell upon the assembled teachers and students. Everyone was afraid to talk, for Newtown was a Catholic school and, therefore, a calypso-free zone.

Slinger’s performance upended the moral order, throwing dramatic and incidental light on the options open to a colonized people: resignation or rebellion.

Tags: #caribbean #soca #carnival #trinidad #caribbeanlife #trinidadandtobago #westindies #calypso #westindianculture #trinidadcarnival #caribbeanculture #grenada #culture #calypsoasteachingtool #carnival history #caribbeanhistory #calypsohistory

Caldwell Taylor, founder, and editor of Big Drum Nation was Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister during the People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada from 1982 to October 1983, Mr. Taylor was a former teacher, carnival bandleader, and journalist. He was Grenada’s Ambassador to the United Nations from September 1980 to October 1983. Mr. Taylor lives in Toronto with his wife and family.