|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 13 mins

April 7, 2024

First published in BDN, March 4, 2012

“The Caribbean links the destinies of the Americas” – Dom Basil Matthews Dom1 Basil Matthews, the erudite Trinidadian-born Benedictine monk (191 1-1999), ought to be a fixture in the popular mind of Trinidad and Tobago and the Americas. But unfortunately, he isn’t; indeed, his memory tends to be invoked only in the context of what seemed a cameo appearance in the story of the meteoric rise of Dr. Eric E. Wlliams in the 1950s: “TheDom” at the behest of Count Finbar Ryan, the then Archbishop of Trinidad and Tobago, debated Williams on matters concerning Church and State, education and the central meaning of Aristotle’s corpus; concerning Church and State, education and the central meaning of Aristotle’s corpus; concerned over Williams’s phenomenal rise, Archbishop Ryan wanted to clip the wings of the former Howard University professor of social and political science.

“The Caribbean links the destinies of the Americas” – Dom Basil Matthews Dom1 Basil Matthews, the erudite Trinidadian-born Benedictine monk (191 1-1999), ought to be a fixture in the popular mind of Trinidad and Tobago and the Americas. But unfortunately, he isn’t; indeed, his memory tends to be invoked only in the context of what seemed a cameo appearance in the story of the meteoric rise of Dr. Eric E. Wlliams in the 1950s: “TheDom” at the behest of Count Finbar Ryan, the then Archbishop of Trinidad and Tobago, debated Williams on matters concerning Church and State, education and the central meaning of Aristotle’s corpus; concerning Church and State, education and the central meaning of Aristotle’s corpus; concerned over Williams’s phenomenal rise, Archbishop Ryan wanted to clip the wings of the former Howard University professor of social and political science.

The so-called ‘Aristotle debates’- the Doc versus the Dom or in the irreverence of the Trinidadian streets – “the Deaf versus the Dum”- enlarged Wlliams’s stature in the eyes of the masses of Trinidadians. Viewed as the clear winner over the towering Dom, “Little Eric’ became the people’s champion, for here was an Oxford-educated scholar with the cutting wit of the Midnight Robber: The Robber is a masquerade character that intimidates “pretenders” with his spellbinding oratory and erudition; he is “family” to the Grenada ” History Mas” and the “Carriacou Shakespeare Mas.”

The popular view held that the Dom lost the debates on two counts. First, he did not seem to have Williams’ grasp of the relevant facts. Secondly, his language seemed” too much in the clouds”, perhaps betraying the effects of his cloistered intellectual upbringing.

Be that as it may, it is really a great pity that the Aristotle debates – a wee bit of intellectual theatre – seemed to have provided the definitive statement on Dom Basil Matthews, a pioneering sociologist of the Caribbean family, a pan-Caribbeanist and a pan-Americanist who viewed the insular Caribbean as both a “laboratory’ in which federative principles could be distilled and a “bridge” to the realisation of a federation of the Americas.

These yearnings for regional cooperation and integration put Dom Basil in an intellectual lineage that could be traced all the way back to the nineteenth century and giants like Ramon Betances, Eugenio Maria de Hostos, Gregorio Luperon, and Jose Marti; Joseph Antenor Firmin, the Haitian anthropologist (1850-1911) and author of De D’Egalite des Races Humaine (The Equality of the Human Races), also belongs in this temple of illustrious ancestors.

Dom Basil Matthews died ten years ago this month in Aberdeen, Mississippi, but his pan-Americanist thought is well worth revisiting on the eve of the Fifth Summit of the Americas, which will be held in Trinidad and Tobago from April 17 to 19. It is the first Americas summit to take place in the Caribbean. This is enough of a backdrop, and it is time we met the Dom.

And who was Dom Basil Matthews?

DOM BASIL MATTHEWS – PRIEST AND PASSIONATE PAN-AMERICANIST

THE MAN

“The Caribbean offers an ideal laboratory for the cultivation of inter-American understanding, respect, friendship, and brotherhood”—Dom Basil Matthews (1911-1999), The Commonwealth, Feb. 1943.

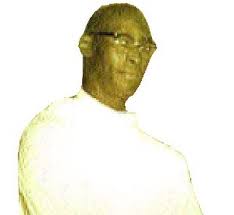

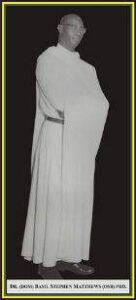

The first installment of this essay ended with the question: And who was Dom Basil Matthews? We shall now try to provide some answers; we will work carefully down from the lofty heights of De Wilton Rogers’s graphic description of Dom Basil, contained in a book entitled The Rise of the People’s National Movement.

Rogers wrote: “[Dom Basil is] a Catholic divine standing over six feet in his socks, finely chiseled and considered the most learned man of his time”2.

The Dom was metallic black, and in his lily white sacerdotal gown, he cut a quite dramatic figure – black skin, white robe.

Basil Matthews was a bright lad from a humble family born in the San Juan (Sa Wah) area in 1911. He attended the College of the Immaculate Conception (St Mary’s College), an all-boys secondary school founded by the Roman Catholic Holy Ghost Fathers in 1863: the school’s roll of notable alumni includes Malcolm Nurse (1902-1959), who changed his name to ‘George Padmore” when he converted to communism while studying in the United States in the mid- 1920s. Raymond Quevado (1892-1962), a calypsonian and one-time legislator far better known as” Attila the Hun’, was also a St Mary’s old boy.

Attila was singing calypsoes when young Basil Matthews left St Mary’s in 1928 and went up – literally and figuratively – to the Mount St Benedict’s Seminary to commence his studies for the priesthood. Matthews took his priestly vows in 1935 and then went on to the Benedictine College of Theology in Louvain, Belgium; from Louvain, it was on to Fordham University, New York, where he earned a Master’s degree in sociology: He also took a Ph.D. at Fordham.

In the United States, Dom Basil taught at Fordham University, the Graduate School for Social Work, Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart (New York), Howard University, and Talladega College, Alabama’s oldest historically black college.

The Dom was in the U.S. in 1943 when he became one of two New York-based Trinidadians recruited by Eric Williams to assist with the planning for a conference on the theme “The Economic Future of the Caribbean.” Eric Williams hosted the conference at Howard University in Washington, DC., in June 1943.

The conference featured learned presentations by several experts, in addition to a lively “Public Discussion,” during which time Dom Basil seized the opportunity to warn the British and American officials to present that the writers of their “development plans” needed to be equipped with a genuine understanding of the cultural attitudes and behaviors of the people who were to be “developed” by those plans.

By the way, the 1940s saw the birth of ‘development planning” in the Caribbean. The British Colonial Development and Welfare Office was feverishly writing plans in the wake of the passage by the British Parliament in 1940 of the Colonial Welfare and Development Act, and the Americans, too, were scribbling up plans for the development of their portion of the Caribbean world. With all this new planning on his mind, Dom Basil told the Conference:

By the way, the 1940s saw the birth of ‘development planning” in the Caribbean. The British Colonial Development and Welfare Office was feverishly writing plans in the wake of the passage by the British Parliament in 1940 of the Colonial Welfare and Development Act, and the Americans, too, were scribbling up plans for the development of their portion of the Caribbean world. With all this new planning on his mind, Dom Basil told the Conference:

“Socio-economic reform has never taken place within a vacuum. lt takes place within the framework of a definite people with a definite set of institutions, traditions, manners and customs, mores and values about men and life and things, and special machinery for realizing its values and achieving its ideals.

“Failure to gear socio-economic reform to the cultural setting was one of those ‘haphazard cultural attacks ” which made it possible for Puerto Rico to “seethe with misery” despite 44 years of American Rule and three hundred million dollars spent for socio-economic reconstruction. The recent economic disturbances in the British West lndies [1937-1938] point to a similar cause. Likewise, the gaucherie with which Government and foreign missionaries so often approach the family problem, the crucial social problem of the West Indies, emphasizes the immediate objective of an enlightened program of social and economic reform. A scientific sociology of the West lndies must light the path of socio-economic reform in the Caribbean”((Frazier and Williams, Eds. The Economic Future of the Caribbean, p.36))

Ever the sociologist, Dom Basil wanted to ensure that the planners understood that the cultural particularities of the region needed to be uppermost in their minds: he wanted development planning to be isolated from the travelogues of the ‘visiting experts’.

It bears pointing out that Williams brought to his Howard University conference a provocative mix of establishment figures and established Caribbean radicals: Trinidadian Charles Augustin Petioni (1883-1951), a Harlem-based medical doctor, belonged in the latter category. An incorrigible Black nationalist, Petioni was up to his old mischief (Williams saw to that) when he bowled to conference presenter, member of the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission (AACC) and Governor of Jamaica, Sir John Huggins, this googly:

Petioni: I am pleased to learn of the large array of experts with degrees serving on the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission and under its auspices, as developed by Captain Huggins. However, I reject the thought that no West Indian, white or black, can be found either in England or America who possesses degrees. It is clear, therefore, that the Commission is not serious about its statements. It cannot benefit the West ladies so long as it excludes men of the Caribbean who know the conditions of the Caribbean and who have the benefit of European or American education. Therefore, I would like to ask Captain Huggins why West Indians have not been included in Sir Frank Stockdale’s Organization [the British Office of Development and Welfare in the West Indies or on the Commission]3

The question caught poor Captain Huggins off guard. He responded, “I am afraid I cannot answer that question.” Williams, Dom Basil, and Petioni were clearly a single team at the conference. Note: Dom Basil’s comments about the importance of culture and the cultural setting was a back-handed call for the involvement of indigenous minds, the point Dr. Petioni made in a more explicit manner.

And let us be clear: Dr Petoni had two black men in mind as he directed his question to Captain Huggins; the two who were actually in the room were Eric Williams and Basil Matthews.

Dom Basil and Mlliams were of one mind at the 1943 Howard University Conference: Would that have been the case in September 1956, when Dom Basil was taking up the principalship of a St Benedict’s College and Williams was embarking on his first Administration?

Did the two men become enemies on account of the bitterness of the political campaigns of 1956, when the Catholic hierarchy assailed Williams’s pro-abortion views, and members of the Church hurled imprecations at PNM supporters, saying that the letters PNM stood for Pre-Natal Murderers?

Williams went about governing the country, and Dom Basil went about growing a new school, a comprehensive secondary offering academic, commercial, and industrial courses; it was the first of its kind in Trinidad and Tobago.

The Dom explained that he created St Benedict’s “to cater for the children from the countryside who could not make it to town and did not have a chance at even passing the Common Entrance Examinations’. The new school reified in bricks and stones Dom’s desire to upset the prevailing social order, for the social scientist was well aware of the fact that for the poor, education was the sole means of social mobility.

St Benedict’s College was also an expression of Dom’s theory of education, a theory that was in keeping, he believed, with the developmental agenda of the country. There could be no development in the absence of certain basic skills. Of course real development had to be under local direction and control.

Music, soccer and competitive sports were important activities in Dom Basil’s St Benedict’s: He brought in music teachers from England until he was able to procure the services of a local, Major Rupert Dennison, a onetime director of the Police band.

But Soccer was the Dom’s great passion; it was what animated him most: he was a soccer fanatic and he passed this love of the beautiful game to the boys of St Benedict’s. The Dom brought in soccer coaches from Europe and South America and in a short while St Benedict’s became the dominant team in the inter-collegiate league, producing players like Warren Archibald, Bobby Sookram, Jan Steadman, Leroy Deleon and Allan Cupid, Dick Furlonge, Wilfried Cave and Kenny Joseph.

St Benedict’s and the Dom took soccer to new heights and this explains why there are many who insist that Trinidad and Tobago’s trip to the World Cup left the country in the debt of Dom Basil Matthews, a soccer pioneer.

Alas, the Dom was drummed out of St Benedict’s in 1968 amidst allegations of financial misconduct; though never substantiated these charges will shadow him to the grave.

The Pan-Americanism of Dom Basil Matthews

“The rhythm of the Calypso is heavily Latin American. The basic rhythmic pattern is what is known as the Habanera. This rhythmic form is a Spanish modification of unmistakably African rhythm, and it has come to be regarded as the characteristic of Spanish music…We therefore have, in a way, the union of Spanish spirit and African technique” – Dom Basil Mathews (1911-1999)

ldeas do not fall from the skies like rain; no, we make them in historical space and time, in the foundries of our lives. We distill ideas from our individual and collective experience; we borrow them from friends and enemies, from neighbours and strangers; we find them in stories told by our parents and grandparents; we discover them in books, newspapers, songs and so on.

All of this suggests that Max, an insightful historical sociologist, made a brilliant synopsis of the dialectics of change when he wrote that “men [and women] make their history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past”. [Marx, the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte]

Dom Basil Matthews would have drawn his ideas from all of the sources given above and from his Roman Catholic faith.

The Dom was familiar with the history of Trinidad and how it was once viewed by the British as the gateway to doing business with South America’s fledgling republics.

The Dom would have read many Latin American scholars and thinkers; he would most certainly have read Simon Bolivar’s Letter from Jamaica (1815) and his message to the Congress of Angostura (1819). In the latter missive, the Liberator wrote:

“Let us bear in mind that our people is neither European nor North American, but a composite of Africa and America rather than an emanation of Europe”.

The Dom would also have read Jose Marti (1853-1895), the Cuban man of letters who talked and wrote about our “mestizo America”: Marti envisioned the coming of a federation based on our mingled bloods (mestizaje). The Mexican Jose Vasconcelos echoed Marti and Bolivar, he saw an America made up of what he called the” final race, the cosmic race”. ( La raza cosmica, 1925)

But race would not be the organizing principle in Dom Basil Matthews’s conception of a federation of Latin American/Caribbean states: for him that federation will be predicated on Roman Catholicism, a matter that would, in addition to geography and culture, make the West Indies ” eminently fitted to bridge the gap between North and South America” (Commonweal magazine, November, 1942)

The idea of an American federation predicated on Roman Catholicism seemed clearly out of step with the Latin American world of the 1 940s: In the 1940s urbanization and industrialization were fast dissolving the power of the Church; additionally in response to the Great Depression the region had been experimenting with new and supremely secular solutions that contradicted the Church and religion.

This was a time that fired the imaginations of Latin American scholars, including economist Raul Prebisch (1901-1986), whose dependency theory helped to revolutionize the thinking on imperialism and the problems of making economic development happen in the ‘periphery’.

Prebisch wanted to turn the Americas into a trade union of the marginalized poor and oppressed and the way to do this involved “structural” and institutional changes in the world of trade and economics; these conclusions brought on a raft of import substitution policies on the part of Latin American States, as well as calls for solidarity around economic issues. It was this mood that brought the formation of the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA) in Santiago, Chile in 1948.

Dom Basil took a different approach. He viewed “hemisphere solidarity between the Americas as a matter of inter-cultural understanding, and respect, of penetration and appreciation” (See Commonweal Feb., 26, 1943). He saw the British West lndies as being a Latin culture under a veneer of Englishness; in making his case for the Latiness of the British West lndies, he said:

“It was the French and Spanish settlers who as peoples, exercised a determining European influence in the influence in the evolution of the British West Indian people. From the very start they settled on the soil, as did the Africans. This is of no little significance. It is a finding of modern sociology that common existence and common experience upon a common soil through a prolonged period of time is one of the essential elements in the making of a new people. The British West lndies, then, represent an organic mixture of Spanish, French, African, Anglo-Saxon manners and customs-an ideal meeting ground between the more purely Latin peoples further south and the purely English peoples further North” (Commonweal, February, 26. 1943)

The South was of course wholly Catholic and in the North, the United States, there were twenty million Catholics – a sufficient number of these U.S. Catholics , said Dom Basil, could be ” lifted out of the cramping conventions of their surroundings to associate freely with coloured people in the Caribbean and elsewhere”.

Dom Basil’s Catholic vanguard will be joined by ‘the American who figured in the Rockefeller lnternational Houses’. The Rockefeller man “was temperamentally cut out to be builder of a true lnter-American spirit. And the number of these Americans is not as small as might be imagined”. (Commweal Feb. 1943)

It bears pointing out that the calypso figures in the Dom’s theory of federation; indeed, in an article titled “Calypso and Pan America” (Commonweal, November, 1942), he suggested that the calypso was the most expressive symbol of our heterogeneous cultural heritage in the West lndies. He wrote: “Calypso, in its present form, is one of the several types of music evolved by the African Negro in Trinidad. lt is what its name says it is, a gay or festive song” …But calypso ls not only a song, it is action sung. ( Commonweal November 13, 1942)

And he pays a wonderful tribute to the song form when he says: ‘And the songs themselves, the Calypsoes, are to a far greater extent the story of the people. Historians show us the face of the people; these ballads take us into their heart and soul”. (Commonweal, November 13, 1942)

After explaining his theory of the origin of the word “‘calypso”- he thinks it is derived from the French carousseau – a quite tenable position, especially in light of the fact that the calypso was decanted in French/ French Patois until the 1880s – Dom Basil goes on to this non sequitur:

“The calypso lyrics give the strongest informal evidence of the all-pervading Catholic tradition of the Latinized British people of the West lndies. Death, judgment, Hell, Heaven are often referred to’. (Commonweal, November 13, 1942)

Was the calypso preoccupied with the all-pervading Catholic tradition”?

Much of Dom’s data were correct but the same is probably not true of many of his conclusions: wrong conclusions are inevitable whenever a belief system — communism or Catholicism, it does not matter – is made into a procrustean bed.

But of course nothing traduces the sincerity of Dom Basil’s lofty Pan-Americanism: indeed, the white-robed honesty of his pan-American ambition will glow in the discussion halls of the Fifth Summit of the Americas.

Caldwell Taylor was Grenada’s Ambassador to the United Nations (September 1980 to October 1983), and Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs (1982 to October 1983). Mr. Taylor is founder and editor of Big Drum Nation.

Caldwell Taylor was Grenada’s Ambassador to the United Nations (September 1980 to October 1983), and Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs (1982 to October 1983). Mr. Taylor is founder and editor of Big Drum Nation.