|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 11 mins

February 26, 2023I. Prologue: ‘A Source of Authenticity’“I think every poet of any modesty hopes to make just a small contribution to the sound of the world’s hum.”–Derek Walcott“Ah fraid he jail me like he jail Rex Lassalle.”

–Chalkdust, “Ah ‘Fraid Karl“

“The Commonwealth Court Martial was my 3rd Court Martial… I never accepted the Colonial narrative that was its dominant feature and openly challenged it when… BS came up.” –Rex Lassalle, February 6, 2023

Who, then, is this man Rex Lassalle? And from which source springs his hope? Though he says that he only started writing poetry in the 1990s as “the passing of someone might stir [a poem]… or on some memorable occasion one may arise,” he may have been in the poetic realm his entire life. And this led to his second court marshal in late 68 early 69. In the very rigid and hierarchical setting in which soldiers are just cannon fodder for the dictates of their seniors, rather than carry out an outlandish and vindictive order, Lassalle recalls the incident as if it were yesterday:

Mr. Lassalle I am giving you a DIRECT ORDERto give them some instructions.Hugh…why all this drama with this,no need for it.Mr Lassalle…This is a DIRECT ORDER…Fock You, Hugh, You give them those orders!…

While Lassalle says that the encounter, which played out within earshot of soldiers, led to him “losing a few brownie points,” reimagining the event today aware of the “ripening that time brings to such experiences,” he writes, “As I reflect which I did not connect with before…is that [the senior officer] was pulling rank with soldiers whereas they knew I don’t do that with them… Hence problems with family, wife, children they would come and talk to me.” In centering the new vibes which were being fashioned among soldiers before the deaf military brass, Lassalle describes “a process where trust is built, the chemistry of that manifestation arises from being a source of authenticity. Your word means something and can be trusted.” In short, the base for a new and just army and, by extension, society was being fashioned, almost covertly, in opposition to the old imperial order, especially among “The colonial clones allergic to dreadlocks!“

Speaking against the backdrop of the unfilled hopes cultivated by the Williams’ government, Lassalle opines, “So though the society at large was in a neo-colonial lockdown with how it was operating, attempts were being made to create [a] military culture and this was CRUSHED, and all that [Raffique] Shah and myself put forward was thrown in the bin.”

II. Bridge/Movements (Of The “People’s” Army)

“Ringing the Bell for Freedom” while speaking to the milieu that shaped him, Lassalle continues, “I am from Belmont Valley Road; I was bringing that same vibe as an Army Officer. Sandhurst and its social elitism did not give me such a blood transfusion. The Valley Road and the Shango Yard drumming with the Tassa drumming on the hill and the Pan beating was what became present in those racist moments at Sandhurst. That was my back…I did not have to go looking for it. That was present.” Indeed, in a recent email chat with Roger Toussaint and me about his 1970s experience and discovery and fashioning of aspects of his past and present life through poetry, Lassalle noted, “Poetry as a vehicle of expression is obvious. Growing up in Belmont… rhythm was always around.” He cites the rich cultural streams that informed him, even recalling as a ten-year-old being mesmerized by Bertie Marshall tuning pans in his neighbor’s yard. He “just sat and watched, from his steps, as his friends drifted away… [and] was taken into another world of creation.” It was as if the ace tuner were “bringing a being into life.” Little wonder that in his book Grasshopping Through Time, he acknowledged “the music of the steel band and its endless styles of innovations with classical, pop, and calypso music.”

Casting a sharp eye back to the multiethnic, multicultural Belmont landscape, he continues:

when you add kaiso into that, it leaves me looking for a line that starts to embrace that rhythm–those sounds, those situations, and experiences. So I guess [poetry] is more an extension of my environment, where at some level I seek to dingolay with it.”

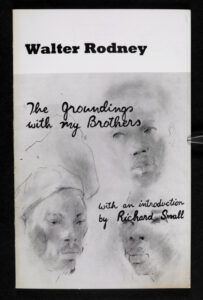

when you add kaiso into that, it leaves me looking for a line that starts to embrace that rhythm–those sounds, those situations, and experiences. So I guess [poetry] is more an extension of my environment, where at some level I seek to dingolay with it.”They project history and April 70 narrativesBased on dumb, idiotic soldiersJust there to be given ordersThey then follow.Never was in a barrack room.Never knew Teteron barrack rooms,Where Fanon & Debray were discussedGiap & Ho Chi Minh were heroes…Those dumb soldiers will just follow ordersFrom their officers In the Colonial narrative.Wishful thinkingOfficers & Senior NCOs would fall into such a horror movie.O, you exaggerator!Really?Dumb Teteron soldiers refused 1969 Christmas lunchA battalion of private soldiers said “No.”…Camp Ogden Barracks burnt down April 21, 70Officers with Colonial script will restore order on April 21, 70…They are not Teteron Barrack room ones.Rodney Groundings was read.Plus, Friday’s Vanguard paper* was in the barrack room,Not forgetting CLR’s Black Jacobins [Complete poem]

inspired by the tenor of the times; their commitment to social change and a just and moral society went way beyond the barracks, envisioning the upliftment and transformation of society.

inspired by the tenor of the times; their commitment to social change and a just and moral society went way beyond the barracks, envisioning the upliftment and transformation of society.Confirming this, Brizan, in a recent WhatsApp conversation, notes: “The young Sandhurst officers met weekly to reflect on the state of the military and ponder our role in the social chaos. One week before King’s assassination, we, Raffique Shah, Rex Lassalle, Michael Bazie, I, [and others,] were searching our consciences to determine whether we would bring our military training to defend the tyranny of the minority, the injustice of the times in Trinidad and Tobago.”

III: Rewind: ‘Just A Boy Scout’?

“Rapso man come to boom, boom up history, boom up history now.Man, tell me what we teaching the childrenTo follow the system

Underscoring his commitment to capturing the revolutionary scenes among the soldiers before the February Revolution, Lassalle employs poetry again to critique and dismiss those whom Sparrow says are “fighting for progress to stop.” In “Indigenous Uprising,” the patriot offers,

Am I not allowed to ask about my past?

Am I not allowed to embrace other possibilities

Than the one that my education gave me?That Columbus discovered Trinidad in 1498

Am I not allowed to ask what happened before?

Are you going to dismiss me and demonise me

Well aware my questions are awkward

As they could create other narratives

That shake the foundations of power?…Am I not allowed to own my authentic humanity?

Rather than the one created by Colonised lenses

Can I not share my personal experiences?

As awkward and different from the norm

From how your Colonised eyes see me…

“Mutiny had nothing to do with Black Power.”This is a falsehood that seeks to perpetuate the colonized mindsetThis is what I am now hearingIt was about a promotion grouse.That never came out of my mouthAt the Commonwealth Court Martial.

That disowning and dismissingOf the idealism of a generationIt has to be challenged…This is where the narrative changes for meMy light skin and middle-class ancestryAlthough viewed as part of the colonial hierarchySimply does not accept that dehumanizing role.. [Complete poem]

Trapped in a colonial mindset, he charts a course of liberation grounded in indigenous knowledge. Lassalle recalls that in the build-up to 70, his mother gave him an order when he was in his uniform one lunchtime. ‘Rex, come sit on the floor in the living room.’ He recalls, “She then plaited my hair in cane row. She never did this before.”

Never saw her with any such book.

What indigenous instinct was driving her conversation?

No need for her to read Mao…

Such aspirations were already streaming through her DNA.

From ancient times long before the Columbus distortion.

My mother’s sister in Harlem

Telling me when I visited

Just after Sandhurst, I came out of the car:

She was there with that

Indigenous finger shaking in my face

“Rex, always remember,

By Any Means Necessary!” [Complete poem]

Lassalle explains his Harlem Pilgrimage: “My mother… linked me with Aunty May when I was at Sandhurst after I told her about the racism at Sandhurst. [Aunt May] invited me to Harlem straight after military training… to lay it on me over two weeks.” Homegrown and indigenous knowledge at its best! Lassalle concludes/affirms: “Those ancestral dots are much clearer now.”

Yet, the first time his father visited him in prison during the State of Emergency, Lassalle recalls his father’s statement,

“Rex, the things I heard about this Army, why it took you so long to do this? You should have done this ages ago!” Reflecting deeply on these seemingly random incidents, Lassalle suggests, “My parents were ahead of me with their Revolutionary zeal. I was just a boy scout to where they were!”

Replaying that when he exited the prison, some of his mother’s ‘middle-class’ friends phoned her to ask, “How is Rex, and what is Rex doing?” His mother, attuned to the rhythm of the streets, would answer, “Rex selling guns; what you want to order? Machine guns, grenades, pistols!” The revered soldier continued, “she responded that way although she knew the phone was tapped.” His parent’s fearlessness in voicing truth to power is the kind that fashioned his informal education, inside and outside the barracks.

Lassalle notes the irony of never hearing overt political statements from his parents before at home. However, he notes, they were deadly serious about a fundamental change in the social structure. Yet he recalls they had great discussions with Lennox Pierre, a social activist and an early supporter of the Steelband, when ‘high society’ denigrated the new musical form. Lassalle adds, “Lennox was the first person my father took me to see within an hour of being released from prison.” In addition, Pierre and Alan Alexander, the lawyer who represented Lasalle, were great supporters of his parents during the ordeal of his incarceration.

IV. Coda: This Man Lassalle…

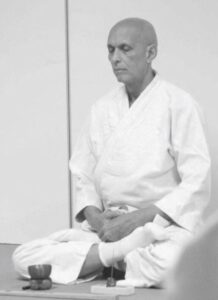

Rex Lassalle is a world-renowned Master in Shiatsu, a form of massage based on the Acupuncture System.

From early, he determined not “to follow some script of accomplishment laid out by others that you seek to emulate,” which has been a guiding principle throughout his life–following his authentic self. So, Lassalle wonders, “Who am I in this conversation of life?”

Circling back to what his father told him on leaving prison, “Rex, there’s no IRA [Irish Republican Army] here, so you gotta leave as you will sacrifice your life, maybe one other… Go away and start a new life.” So leaving Trinidad on January 27, 1973, six months after his release from prison, he returned in 1980 with the sounds of Andre Tanker’s “I went away and ah leave and ah come back home” in his ears as backbeat and started a health food store–” which went on till about September 83′–emphasizing the centrality of nutrition to a nation’s well-being.

Grasshopping through time on a journey of self-discovery and awareness while developing a deep interest in Eastern philosophy and becoming a Shiatsu teacher outlines in his work and writings how people can tap into their innate strength to “navigate harmoniously through life.”

This is the disposition that’s animated his vision of being an advocate of change in critical veins of life and society. Lassalle now lives in Finland, where he takes a deep interest in Eastern philosophy. Always staying connected to the music and culture of his homeland while casting a keen eye on Trinbago and the region, his “Self Care Manual For A Vibrant, Youthful Feeling & Appearance” is well suited in these stressed times. And he has a Lifestyle book in the making that is oriented to Caribbean wellness. In applauding his efforts, Rawle Gibbons, Caribbean playwright and director, remarked, “Thank you for your example of patriotism and continued commitment to the upliftment of Caribbean people!” NUFF RESPECT!

*Conversations between Rex Lassalle, Roger Toussaint, and Winthrop (troppy) Holder occurred online and on the phone between January 15 and February 26, 2023.

Notes:

1. Davis Brizan, Long Live The King! January 22, 2022. Big Drum Nation.

W.R. (troppy) Holder is co-editor of Big Drum Nation, and the author of Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless.

This was a good and interesting read. I like the sequence and how things methodically tied into each other, holding my interest.