|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 6 mins

January 23, 2023

“Our culture needs both preservation and resurgence; our cries need an epiphany, a spiritual definition, and an art can emerge from our poverty, creating its own elation.”

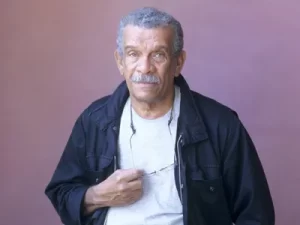

As we celebrate Sir Derek Walcott’s birthdate, his play ‘Ti Jean and His Brothers‘ reminds us how Walcott’s work is revered and grounded in the Caribbean experience.

Little wonder he called this play one of his most Caribbean plays. It is representative of a theatre of the people; as he noted, they “present to others a deceptive simplicity that they may dismiss as provincial, primitive, childish, but which is in truth a radical innocence.”1 Similarly, Rawle Gibbons speaks of Caribbean theatre as “an authentic indigenous theatre… grounded in the Caribbean experience,” one fashioned as a form of resistance to slavery and colonialism imbuing themes central to shaping Caribbean society and integral to the relationship between cultural identity, artistic creation, and the struggle to create a transformative and activist theatre for the oppressed.(( (2017) ‘Rawle Gibbons and the Theory and Practice of the Third Theatre,’ Caribbean Quarterly, 63:2-3, 183-202))

Little wonder he called this play one of his most Caribbean plays. It is representative of a theatre of the people; as he noted, they “present to others a deceptive simplicity that they may dismiss as provincial, primitive, childish, but which is in truth a radical innocence.”1 Similarly, Rawle Gibbons speaks of Caribbean theatre as “an authentic indigenous theatre… grounded in the Caribbean experience,” one fashioned as a form of resistance to slavery and colonialism imbuing themes central to shaping Caribbean society and integral to the relationship between cultural identity, artistic creation, and the struggle to create a transformative and activist theatre for the oppressed.(( (2017) ‘Rawle Gibbons and the Theory and Practice of the Third Theatre,’ Caribbean Quarterly, 63:2-3, 183-202))

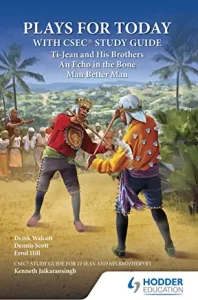

All three plays included in the collection, Plays For Today, edited by Kenneth Jaikaransingh, are classics of Caribbean theatre and center on themes of resistance, rebellion, Caribbean folklore, and mythmaking while using the idiom of the people–what Kamau Braithwaite refers to as “nation language.” They are grounded in the reality of the Caribbean experience and wrestle with the legacy of enslavement and colonialism, and being.

The first play in the collection is Walcott’s ‘Ti Jean and His Brothers,‘ wherein Walcott explores the Caribbean milieu. He draws on St. Lucian folklore to ponder the dilemma of a poor mother and her three sons who live in a mystical forest and are confronted by magical creatures and the devil/planter in many disguises. The play is set in an unspecified place in the Caribbean and tells the story of three brothers who are challenged by the devil, who is striving to grow human(e), so he can enjoy the evil he has wrought. The devil promises to grant wealth and property to whichever brother can make him angry. But the other side of the deal is that the devil will eat the brothers he can make angry.

Of the three brothers, Ti Jean, steeped in indigenous knowledge, prevails over the devil much as Black Stalin’s “One Slave” runs away from the plantation and spreads rebellion. On the other hand, his two brothers fall prey to the devil because they each exhibit insufficient qualities to defeat the devil/planter. Gros-Jean embodies the slave generation, which many perceive operating as if brute strength is the answer to all problems. Mi-Jean typifies the middle class with their snob ideals and reliance on presumed intellect; he is the impractical dreamer. Ti-Jean cleverly defeats the devil through cunning and trickery, burning down his plantation and refusing to complete the menial tasks the devil has assigned him. Through his defeat of the devil, Ti-Jean demonstrates resistance, faith, courage, the power of community, and respect for the past. As his mother says to him as he sets out to confront the devil, who takes on various disguises:

The first of my children

Never asked for my strength

The second of my children

Thought little of my knowledge,

The last of my sons, now

Kneels down on at my feet,

Instinct be your shield

It is wiser than reason

Conscience be your cause

And plain sense your sword. (emphasis added).

Just as Walcott in Ti Jean utilized the storytelling idiom “to encompass the expressive elements that typify life as he experienced it in the Caribbean,”((Jaikaransing, ibid, p.5)) similarly Dennis Scott, in the Echo in the Bones, taps into the Afro-Caribbean religious ritual of the Nine Night Ceremony. In ‘Echo in the Bone,’ Dennis Scott centers the action around the traditional Nine Night Ceremony held to honor the deceased’s spirit of Crew, who had killed a white estate owner and then committed suicide by drowning himself. Crew’s body was not found, but the family still held the traditional ritual nine nights after death to assure the deceased’s soul that all was well. The ceremony takes the participants on a journey where they re-enact elements of black history, including the harsh treatment of the Africans on the slave ship, followed by a distasteful auction and, subsequently, the horrific treatment by plantation owners of the enslaved.

The play’s underlying message seems to be that despite a horrendous history, one should take the rite of passage and embark on a journey of love and acceptance. In the play’s final scene, Rachel says: “No matter what is past, you can’t stop the blood from drumming, and you can’t stop the hearts from hoping. We have to hold on to one another. That is all we can do.” Scott’s aim in this play, as illustrated by these final lines, is that we must, as a people, reclaim the past, our voice–the echo in the bone–but not let it hold possession over our lives but act as a guide to uplift and a spur to freedom.

Finally, Errol Hill’s ‘Man Better Man‘ celebrates the artistry of stick-fighting, a folk experience which, like carnival and playing mas, was once denigrated under colonial rule. This dance-like spiritistic art form which features martial art moves, was brought to the Caribbean by African enslaved in the latter part of the 17th century. Back then, the enslaved from the Congo and Angola used the gayelle or stick fighting arena to rid themselves of the trauma of slavery. The play tells the story of a young man, Briscoe, who enters the ring of stick fighting against the fearsome local champion, Tiny Satan. To win the love of the proud and flirtatious Miss Lily, he seeks the help of the local Obeahman, Papa D, who offers to help him win. But Papa D schemes to outwit Tiny and the other villagers by betting on the ensuing stick-fighting battle between Tiny and Briscoe. Man Better Man memorializes aspects of Caribbean folk life–stick fighting–which is now celebrated as a source of cultural identity and pride and actively pursued as an art form-Kalinda-in villages like Moruga in Trinidad.

Jaikaransingh’s book is an excellent resource for teachers and anyone interested in Caribbean literature. As a study guide for Caribbean students getting ready to take the CSEC exams, there are some essential questions to ask: How does this book stand up to other similar study guides, and does it provide a clear and understandable way for students to prepare for the exam and an informed life? For example, in the section on Answering The Essay question, Jaikaransingh advises the reader that “Answering a literature question is like preparing a legal argument.” One must be succinct; less is more.

Even though the study guide is only for Walcott’s play, its format can easily be adapted to the other plays, given that all three focus on similar concerns and themes. In the section on Themes, the author succinctly sums up the central ideas, themes, and motifs, running through the play, from good and evil to resistance and rebellion. In the section Dramatic and literary Technique, the author mentions Aristotle’s seven elements of drama and then discusses the equivalent of Aristotle’s “spectacle” in modern drama.

This comprehensive, well-thought-out book introduces Caribbean theatre to all audiences interested in Caribbean history and literature. Its breakdowns of plot, character, setting, production details, information about the authors and the adaptation process, and discussions of themes and images are excellent. It is meant to challenge the reader and deepen their understanding and connection to the plays. Plays For Today comes complete with pre-reading activities (preliminary activities, questions and activities, close reading activities, and post-reading activities), giving the student/reader an in-depth theatrical learning experience that positions them to become literary change agents in their communities.

Plays For Today also has a brilliant essay/introduction by Errol Hill, one of the playwrights presented in the collection. It is a tour de force as it introduces us to the dynamics of each play and gives us an insight into each author as the author/editor suggests that students studying the Guide for CSEC exam must read Professor Hill’s essay after their second reading of the plays “to see how many of the observations [they] agree with or have picked up on [their] own.”

Jaikaransingh’s guide is an engaging introduction to the theatre of the Caribbean for specialists, students, and laypersons alike because it presents three representative and significant dramas of Caribbean literature and highlights how theatre is not only an antidote to the instant gratification of YouTube, TikTok, etc. but a medium of cultural renewal. As Walcott noted, “Our culture needs both preservation and resurgence; our cries need an epiphany, a spiritual definition, and an art can emerge from our poverty, creating its own elation.”2

Lennel George, a retired NYC High School Principal who teaches at C.W. Post, Long Island, is a Kittitian with a deep interest in Caribbean Literature and has traveled throughout the region, including Cuba.

Lennel George, a retired NYC High School Principal who teaches at C.W. Post, Long Island, is a Kittitian with a deep interest in Caribbean Literature and has traveled throughout the region, including Cuba.