|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 6 mins

March 7, 2022

Potier… did for the Caribbean and me more than a posthumous eulogy could narrate.

If you never believed in the miracle of self-reconstruction, you should check out Sidney Poitier’s life. It will alter your belief. Nothing in the stars destined him for stardom, certainly not in the pure white enclave of a racist Hollywood in mid-20th century America. But he did become a Hollywood superstar, paving the way for Denzel Washington and others like Guyanese-born actress Letitia Wright of Black Panther fame and Dominique Thorne, a New Yorker of Caribbean parentage, who will debut in Black Panther 2. Indeed, Poitier foreshadowed and opened a path for many Black thespians to achieve success in the unlikely nook of white American conservatism. But he did a great deal more for countless others, who at some stage had lost faith in their ability to be somebody. As a Bahamian, he did for the Caribbean and me more than a posthumous eulogy could narrate.

If you never believed in the miracle of self-reconstruction, you should check out Sidney Poitier’s life. It will alter your belief. Nothing in the stars destined him for stardom, certainly not in the pure white enclave of a racist Hollywood in mid-20th century America. But he did become a Hollywood superstar, paving the way for Denzel Washington and others like Guyanese-born actress Letitia Wright of Black Panther fame and Dominique Thorne, a New Yorker of Caribbean parentage, who will debut in Black Panther 2. Indeed, Poitier foreshadowed and opened a path for many Black thespians to achieve success in the unlikely nook of white American conservatism. But he did a great deal more for countless others, who at some stage had lost faith in their ability to be somebody. As a Bahamian, he did for the Caribbean and me more than a posthumous eulogy could narrate.

Sidney Poitier was born in Miami, Florida, on February 20, 1927. When he died at 94 on January 6, 2022, he was a long way from the difficult economic circumstances of family life in the Bahamas, where he lived until age 15. Then, his parents sent him to live with an older brother in Miami. They figured he would have better opportunities.

As a Caribbean man, I identify with Poitier’s experiences because, like some Caribbean parents, my father had deposited me in London to live with Leon Zoe, an older brother. The latter had no interest in guiding a fifteen-year-old young man through the rigors of life. I was bewildered. Leon was busy pursuing a medical career and could find little time to chaperon me through dangerous days in the summer of 1967. Then London was no less racist than liberal New York and required a rugged approach to surviving the biases of second-class citizenship, the kind of prejudice that haunted Poitier in his early career. So off I went to a theater in Brixton to see “To Sir, With Love,” a transformative British drama about an idealistic teacher played by Sidney Poitier who must win over rebellious teenagers in a tough East London school.

By that summer, Poitier had already overcome his impoverished background in the Bahamas and adjusted to American culture to rise to the top of his profession at a time when prominent roles for Black actors were rare. He had won the Oscar in 1963 with “Lilies of the Field,” playing an itinerant laborer who helped a group of White nuns to build a chapel. In my early Caribbean days, a few friends and I had become truants and ‘break biche’ to see this movie. Before leaving the Caribbean in 1967, I had already seen “No Way Out,” “Cry, the Beloved Country,” a troubled student in “Blackboard Jungle” and an escaped prisoner in “The Defiant Ones,” in which he and Tony Curtis were shackled together and forced to get along to survive. With “Defiant Ones,” Poitier became the first Black man to be nominated for an Oscar. He appeared in the first Broadway production of “A Raisin in the Sun” in 1959 and starred in the movie version two years later. Then came “Lilies of the Field,” biblical epic “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” and the drama “A Patch of Blue,” in which his character had a chaste romance with a blind white woman. I was unaware at the time, but in retrospect, Poitier was fortifying me to be defiant and resolute in my struggles. These struggles resembled countless Caribbean people in London, New York, and elsewhere.

While many of his best-known films explored racial tensions as Americans grappled with social changes wrought by the Civil Rights Movement, Caribbean islands watched and reflected on their own situation. In 1967 alone, he appeared as a Philadelphia detective fighting bigotry in small-town Mississippi in “In the Heat of the Night” and a doctor who wins over his White fiancée’s skeptical parents in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” However, the 1967 film “In the Heat of the Night” gave Poitier his most enduring role. He played Virgil Tibbs, a homicide detective passing through Mississippi when a bigoted White police chief (Rod Steiger) detained Tibbs as a possible suspect in a slaying. After a belligerent encounter in which Tibbs slaps Steiger back (a slap heard around the world), Tibbs reluctantly agrees to stay and help solve the case. The two men eventually find grudging mutual respect. That slap got the Caribbean talking about how to escape the grip of racism. Through Poitier’s return slap, they could sense a new possibility of standing up for a new way of being in a world where they had become tired of the various forms of oppression in the region. Indeed, It was a slap heard around the Caribbean, which, perhaps like the United States of America, was readying itself for a more just society.

“I see each of us as authors and responsible persons for our interpretation and reaction to the circumstances of our lives.” – Sidney Poitier

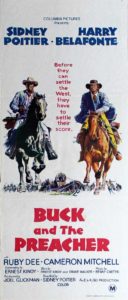

In the 1970s, Poitier scaled back on acting and turned to directing, which he felt gave him more control over his film projects. First, he teamed up with his pal Harry Belafonte for the Western “Buck and the Preacher,” his directorial debut. Next, he directed and co-starred with Bill Cosby in the comedy caper “Uptown Saturday Night,” which, along with its spiritual sequels “Let’s Do It Again” and “A Piece of the Action,” featured primarily Black casts.

Poitier’s dignified roles helped audiences of the 1950s and 1960s envision Black people not just as servants but as doctors, teachers, detectives, and lawyers. It helped me imagine myself as a poet. At the same time, as the lone Black leading man in 1960s Hollywood, he came under tremendous scrutiny. He was too often hailed as a noble symbol of his race and endured criticism from some Black people who said he had betrayed them by taking sanitized roles and pandering to Whites. “It’s been an enormous responsibility,” Poitier told Oprah Winfrey in 2000. But he accepted it and lived in a way that showed how he respected that responsibility. For others to come behind him, there were certain things he had to do.

By 2000, Poitier had retired from acting, choosing to play golf and pen a memoir, “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography.” He described his lifelong attempt to live according to principles instilled in him by his Bahamian father and others he admired. Unfortunately, I was not that lucky. I became a lower-level accountant in London, struggled writing meaningful poetry, and played amateur golf. But the image of Poitier’s success against great odds kept me going, eventually realizing that the enjoyment of life was another form of success.

In the early 1960s, Poitier joined the more outspoken Harry Belafonte and began embracing the Civil Rights Movement. Both men attended the 1963 March on Washington and in 1964 traveled to Mississippi to meet with activists in the days following the infamous slayings of three young civil rights workers.

As a Caribbean man, I learned from Sidney Poitier to nurture that state of being willing and ready to bring all of one’s available resources to confront the difficulties of living or operating successfully in challenging environments. I saw his approach as a model possessing an endless proliferation of freedom to act effectively in any circumstance, speak truth to power, and advocate social justice. This model challenged more traditional definitions of social membership. He was courageous, strong, hardy, rugged, and robust. As he aspired to bring personal mastery into his plan, he established his position clearly, so those around him could quickly take his lead. He knew that unless one was willing to step beyond ordinary actions, there would be the slight possibility for what looked like impossible outcomes to become a reality. A Bahamian Hollywood movie star? An unlikely possibility. It all seemed so magical.

But his commitments found potency when he responded readily to adversarial “forces” by choosing to hold obstacles and problems as opportunities to forward his work, so they did not seriously limit his effectiveness. Resistance to his progress by other individuals became a source of inspiration. Extrapolating this notion of responsibility to life, he used adversity to take responsibility for his actions in the world while helping, even subtly, transform society.

“I see each of us as authors and responsible persons for our interpretation and reaction to the circumstances of our lives,” he asserted. Who can argue with such a noble claim? He became a movie star when the circumstances dictated otherwise. In that sense, I always wanted to be like Sidney. He is the reason I believe in the miracle of self-reconstruction.

Sidney Zoe is a Caribbean accountant who writes poetry and plays golf. Sidney Poitier has been his idol and primary source of inspiration as he straddles those two incompatible domains.