|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 12 mins

PART I of II

November 24, 2024

In the night of the forest, under the pouring rain, Mama Agouti and her offspring huddle together in a hollow of the trunk of the pomerac tree as the light flashes and the angry sky bellows. Do not fret; she tells her shivering children; no harm can befall us as Papa Bois watches over us. He protects all creatures of the forests and swamp lands, and he will make the storm pass and the twinkles of the night blanket come out again like always. But the sky is so angry, say the children, can Papa Bois quell the fury of even the thunder? Yes, Doux Doux Darlings, says Mama. When he speaks, all natural things listen, and he can change the fate of any creature in an instant. The children settle close into her fur, and as the water falls heavy overhead, she weaves them a story to pass the time, as is their custom.

When the forest was younger than it is now, Doux Doux Darlings before Humans made the world hard and cold — when they still lived on the earth, and together with the trees and animals, there was a little girl born to a human mother, not too many trails from here, and her name was Imani. The little girl was like a doll to her family, with long curly hair often sapped with coconut oil, round, sweet cheeks, and bright, curious eyes too big for her head. Each year from her birth, she became more beloved to those around her, and the village elders thought perhaps she was the reincarnation of some mystical being, for in her saucer eyes, there was a sharpness of knowledge beyond her years. Her parents boasted of her to all who would listen, but although they were proud of how she was perceived, they were not always kind to who she was. Still, as they spread the word, the story of this strange and handsome child eventually fell upon the ears of an ancient and powerful LaJablesse who went by the name of Nibagua.

Nibagua was tall and lovely beyond belief, with piercing eyes like garnets, fluffy hair like the clouds, and one cloven hoof at the end of her sturdy left leg, always hidden away behind the folds of her skirts. Many a man had followed her into the trees at nightfall, never to return home to the warmth of their beds, and it was said that to gaze upon her face was to see the true meaning of beauty and despair. And yet, men in their folly sometimes sought her out to catch a glimpse, believing that they would be the ones who could resist her charms and find their way back to the safety of their village, with the memory of her visage stored deep in their heart as a keepsake to hold till their twilight years. But none did.

Little Imani was friend to the animals and brought paw paw and other treats for the birds and crawling things, and stooped in the grass watching the glimmering green iguanas run, the snouted manicou hop with babes on their backs, and the lines of bustling bachacs go to and fro from their nests with torn bits of leaf in their jaws. She found animals easier to be near than humans — including those of her family. Thus, she spent her time with the wild things until soon, even the animals began to speak of her gentle nature and thoughtful eyes. But Nibagua heard one too many forest dwellers tell tales of this child and grew irritated, for she had fallen prey to her mythology and felt that her stories should be the only stories whispered between the leaves and the bark. And out of that irritation grew a seed of jealousy, which budded and rooted deep in her soul until she could no longer bear it and decided to be rid of this human child.

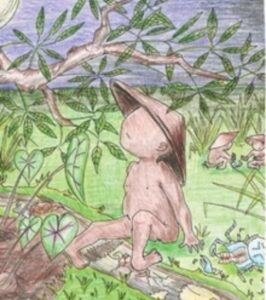

She summoned her dearest son, Atiba, who appeared before her with the delicate frame of a young boy, his face obscured by the shadows of a large straw hat and feet where the heel faced forward and the toes faced backward, for he was a Douen. And she spoke to him the name of the child that had been revealed to her, which is why you must never call out the name of your offspring after dark, Doux Doux Darlings, for a name is a potent thing — even more so in the hands of a spirit. The LaJablesse bade her son find the child and bring her into the depths of the forest, where she might be left to the devices of the malevolent beings that live there. Forever lost to the world, stories of her would trouble his mother no more. Atiba was an obedient son, so without question, he went off searching for the girl to lure her away from her home as Douen has done to many a human child and will do until the rivers dry up and the mountains fall into the ocean.

When the douen found her playing in the stony stream near her home, he called out to her in the voice of her mother, and she followed. Calling and running, running and calling, he drew her deep into the underbrush, through the animal paths that snaked across the forest floor. He was to take her to the dwelling of the great beast, the Lagahoo, a shape-shifter who could be heard dragging chains through the dirt with a form so long his toothed head would disappear above the trees, ravenously devouring any creatures that fell into his path.

But as the girl followed, she hummed a song below her breath, and Atiba found himself inching nearer and nearer to hear what she was singing. And her gentle voice gave him pause until he was so close to her that her dim human eyes could make out his figure in the darkness. She was afraid, but her voice did not waver. She sang to him, and as her music touched his ears, he became unsure of his mission. And in the center of his doubt, there bloomed a softness.

Atiba, like all douen, was forever a child. In his childlike way, he decided, instead of returning her to her people, he would take her to a clearing and construct for her a makeshift shelter to protect her himself from the wrath of his mother. And he would have a friend to play and pass the time, who could reignite for him that distant memory of a humanity he once had.

Children are made of sturdy stuff, Doux Doux Darlings, even in the rainy season when the ground shakes and the swollen clouds blot out the moon’s light as they do now. They bundle up the awareness of what harms and frightens them and continue with it, holding it in their minds like a careful package to be unwrapped and understood when they have grown older. And just so, little Imani grew accustomed to her new living alongside the beasts she had often observed from afar. She never went hungry — for her shadowy benefactor plied her with the fruit of the forest, brought her little gifts of colorful rocks and blossoms and deep crimson roucou for painting, and sometimes played diverting games with her to pass the time. But he never allowed her to look upon his face.

Over time, her diet of mangoes and soursop became inadequate, so Atiba stole from his mother one day the Red Flower, which Imani might learn to roast her food over hot stones, and perhaps then her stomach would settle. At night, the Red Flower kept away the larger creatures so that when Atiba was called away to acts of service for his mother, his little companion would be safe in her shelter. But some nights, he was not needed; he stayed nearby, watched over her, and slept under the stars.

Imani found that the further away she was from her former life at home, the more the animals around her were willing to speak plainly with her. She became acquainted with the frogs, birds, capybaras, and so on, often sharing her meals with them or helping them along on whatever minute daily task they were pursuing. She was an inquisitive child, eager to inhale the world around her. Over time, her interest turned to the nature of her benefactor, and she asked him questions about where he went when he was not here and who his family was, and he tried to answer truthfully as best he could without getting them both into trouble. He told her of his mother and how she cared for him but was very stern and that her name was Nibagua. In turn, she told him what she remembered from home: the smells of the kitchen, the sound of her mother weaving fabric, the cool, flat touch of her father’s cutlass. And they each became fascinated with the life of the other. But the more Imani learned about the boy, the more the thought nestled in her head that she did not know what he looked like.

One night, Imani pretended to doze off, pinched her eyes shut, and counted until Atiba fell asleep on his perch nearby. Carefully, she crept from her cradle of soft grass with a stick brushed with the Red Flower and approached her friend as quietly as she could muster. She reached up, stretching the stick out as far as it could go, and the light illuminated his ghostly face, casting harsh shadows from the brim of his hat. To her surprise, he was just a boy — with smooth, dark skin, gently fluttering eyelids, and a peaceful expression on his face. She drew up onto her tiptoes and inspected him curiously. But as she raised, her grip on the stick loosened, and it dipped down.

The douen yelped and sprang up as the Red Flower grazed his stomach, and for a moment in the brightness, she saw his facial features melt away as if into a fog, leaving only a blankness behind. The noise and movement caused her to start, and she jumped back, exclaiming in surprise. She flung the stick back into the red coals near her camp, and when she turned, Atiba had vanished — but echoing through the woods, she heard a child bitterly crying, and the noise faded softer and softer. Then, it was no more, and she was alone.

For two days, she waited, ate the remnants of the last meal he had brought her, and stacked and unstacked her collection of stones. But then her belly began to complain, and she thought he might not return. She asked Frog if he knew the way home, but he did not. She asked Keskidee if she knew where Atiba had gone, but she did not. Then she asked one of our own ancestors, Doux Doux Darlings, and Agouti said that he knew where the boy would be — in the house of his mother.

Agouti sprang off with a quickness, and Imani followed as best she could, sometimes losing sight of him and then spotting a flash of his red fur in the distant tree line. He would race ahead, sit quite suddenly on his hind legs, and sniff the air as he waited for her to catch up. They crossed the river and went up into the mountainside until he turned and said to her that he would go no further into the territory of the LaJablesse. Still, if she continued along the trail, she would soon arrive at the home of Nibagua and find her son. So onward she went.

The path grew steeper and steeper until Imani crawled up the side of the incline on her hands and knees. Then, a little way ahead, she saw a glittering waterfall that streamed down into the rivers below, and at the bank of the river, there was the structure of a rectangular thatched house, and atop its roof stood the hulking black body of a giant Corbeau. Goodnight, said Imani. I am searching for the home of Nibagua. She stood and waited, but King Corbeau only turned his head and opened one obsidian eye. So she bowed to him and made her way into the house, and he did her no harm. This was indeed the dwelling of the great and beautiful Nibagua. As Imani entered, she saw the LaJablesse lounging in a hammock, fed the flesh of guava by a boy in a wide-brimmed hat. But it was not her Atiba.

What an ugly, grubby little girl, said Nibagua. Why have you come to my home in the dead of night?

Imani drew a deep breath to fill herself with bravery, then spoke. She was looking for the boy Atiba because he was her friend, but she had accidentally hurt him and was unable to tell him sorry, and she was very sad. Nibagua’s lips curled into what might have looked like a smile but was not. She stood up to her full height and walked to the girl, her one hoof clopping against the earthen ground. She said, what would my son want with a grubby little human like you?

“Please,” said Imani, tears welling up in her eyes. And Nibagua faltered, for even she was not made of stone. She thought to herself for a moment and then said to the child, I will let you see my son, but first, you must work hard for the honor, for my sons are most precious to me. The LaJablesse gestured out of the window and told the girl that she would find a crocus bag filled with pigeon peas outside. She must shell the peas and sort them into colors, green, red, and white speckled, and so on, and do so before the first light of morning crested over the hillside. She would be granted an audience with the boy if she were successful. If she were to fail, the LaJablesse would claim her hair as a reward.

The little girl bowed low and left the house, searching for the crocus bag. But she burst into tears again when she saw the bag size she was meant to sort. It was a hulking thing, more significant than her height, filled to the brim with pea pods. She sat down on a tree root in the grass and wrung her hands, for she knew then that this undertaking was impossible for a child of her stature, especially as she was exhausted from walking through the night.

As she cried, her voice was heard by a line of bachacs, foraging for leaves to bring to their colony deep underground. The tiny insects took pity on her, for there was many a time that she had helped their kind before, and so they diverted from their track and climbed the crocus bag, biting through the pea pods and carefully carrying each pea down to the ground, where they sorted them into piles. For hours, the row of bachacs climbed and sorted until the bag was folded in on itself, and the piles of color rose high. And just as the final pea was placed on the top of the final pile, the deep dark blue of the sky began to turn pastel, and the dawn had come.

With the first light, Nibagua emerged from the house. Her eyes widened as she saw the heaps of pigeon peas neatly across the ground. Then she called up to King Corbeau, she do all this? King Corbeau opened one eye. She had help, he said. Nibagua gnashed her teeth, stamped her cloven hoof, and cried out dishonesty! And at my own home too! Like you feel I was born yesterday! Her ire filled the air, but then she calmed herself and settled back into that smile-not-a-smile. Very well, she said. You shall have another chance to redeem yourself, you must be the one to accomplish the task. Or, this time, I claim your teeth.

She detailed the nature of her next errand for the girl, which was more elaborate than the last. Below the waterfall, across the river, a herd of golden quenks roamed for grubs and roots along the bank. You will hear Quenks, Doux Doux Darlings before you see, for the chattering of their tusks echoes far through the wilderness, and you must hide in the underbrush and wait for them to pass by not to provoke them into a rage. And Imani also knew this and trembled as the LaJablesse told her what was required of her — to retrieve a single gilded tusk and bring it before her.

The river was a challenge in itself. With her short legs, Imani waded through as best she could, keeping her weight against the rocks as the water pushed at her. She hummed a little song to the water, asking it to bring her across safely, and so it did. Once she had pulled herself onto the other bank, she spotted a glint of gold not far away. She caught her breath, for there was a troupe of almost thirty pig-like creatures, noses snuffling in the dirt. Their powerful canines were hidden behind their snouts. She had not thought of how she would pry one of those teeth from a mouth without getting gored in the process, but she was young and had not known true pain and so felt perhaps she would be able to take it.

But she was carrying so much tiredness in her body, and she felt it in her limbs. She sat for a moment at the edge of the river. The water babbled as it rushed past, and its cheerful noise began to sound almost like a voice coming into focus until Imani was sure she could hear it say, “Be patient and rest here a while, little one. The answer shall reveal itself with time.” So she closed her eyes and drifted off.

END OF PART I