|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 6 mins

Vaneisa Baksh, Son of Grace: Frank Worrell – A Biography. Fairfield Books, 348 pages. (Paper £22.00)

May 22, 2024

What set Worrell apart was his natural air of authority. He did not need to be in a leadership position to manifest it, and this characteristic defined his life… in the Sixties, until his death in 1967, he was more of an icon as a West Indian leader, whose qualities of grace and wisdom framed him as the ideal representative of a society still constructing its identity. (Son of Grace, p.13)

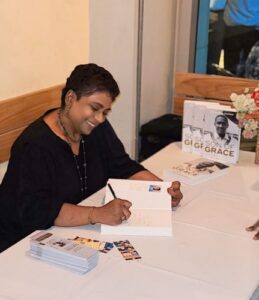

Vaneisa Baksh autographs copies of her book at the Book Launch held at the Dalai Lama, One Woodbrook Place, on April 23, 2024

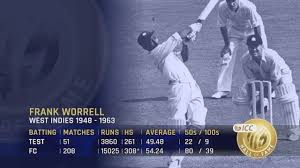

The name Sir Frank Worrell is revered regionally, as much for his cricketing exploits as well as for his singular achievement in harnessing the raw potential of Caribbean people to stamp their achievements and capabilities on the international stage. As player, captain, and ultimately manager of the West Indies cricket team from the 1940s to his untimely death in 1967, Frank Worrell graced the world with his talent, his leadership, his charm, and his ability to inspire West Indians to see themselves as more than mere inhabitants of the little rocks in the Atlantic on which so many of them had been left to founder.

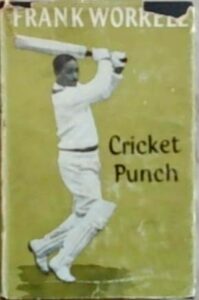

Yet, despite the many accolades that have been laid at his door, Frank Worrell remains an enigmatic figure in Caribbean history. Intensely private and reserved in his lifetime, it is doubly difficult nearly 60 years after his passing to interview his contemporaries, most of whom have passed on, or surviving family members who remain fairly tight-lipped about their illustrious relative. Many articles about him have appeared in cricket magazines or collections over the years, but to date, no major biography has been written, save one by Ivo Tennant. Worrell himself produced Cricket Punch in 1959, which focuses primarily on Test cricket in which he was involved from 1950–57, and offers precious little about his background, childhood and early career.

Vaneisa Baksh’s superb new biography, Son of Grace seems destined to become the definitive and most complete account of Frank Worrell, warts and all, for some time to come. Drawing extensively on personal interviews with people who were close to him, like his great contemporary, the late Sir Everton Weekes, a serendipitously discovered treasure trove of contemporary documents from the West Indies Cricket Board of Control (as it then was), and a variety of other primary and secondary sources, Baksh has created a new and mesmerising portrait of a supremely talented and inspirational figure who, like all of us, was subject to human weaknesses and foibles, which in no way diminish his status as a true West Indian icon.

Son of Grace fills in many of the blanks in what we know about Worrell, beginning with his childhood days in Bank Hall, Barbados; his family connections; his relationship with his mother; the events at Combermere High School, where his affectation for dressing well and spending freely earned him the reputation of being cocky. His experiences there would help precipitate his eventual departure from Barbados and what he considered its oppressive milieu of race and colour prejudice.

Son of Grace also manages to frame the evolution of Worrell’s life and career alongside that of West Indies cricket in the context of contemporary world events and developments. Worrell and the West Indies cricket team began their journey to world recognition in the post-World War II era, which may have coincided with the waning days of the British Empire but which had left its legacy of class and colour privilege and discrimination firmly embedded in island cultures, and continued to manifest itself in the attitude of the WICBC as a power unto itself in the hands of people like Sir Errol dos Santos and Captain Peter Short.

But the world of the Americas and the Caribbean would shortly be caught up in the struggle for political independence and the right of non-white peoples to be afforded their equal place in the sun. Regional euphoria attended the successes of the Brazilian football team, the continued emergence of black boxing heroes in the wake of Joe Louis, like Floyd Patterson and Mohammed Ali, and the political activism of Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

These would all pale in comparison, however, when the regional cricket team defeated the colonial lords and masters on their home grounds in England, then continued to match other cricketing nations as equals both at home and abroad. These would culminate in the famous Australian series of 1960–61, in which Frank Worrell and his Australian counterpart Richie Benaud conspired to rescue Test cricket and lift it from the doldrums. Ongoing successes in international series throughout the sixties would pave the way for the dominant performance of successive West Indies Test teams in the 1970s and 1980s.

Much has in fact been made of CLR James’s relentless campaign to have Worrell named as captain for that momentous tour of Australia, the former being given almost exclusive credit for the appointment of West Indies’ cricket first black captain, if one ignores George Headley’s single Test as captain in 1948. As Baksh’s book reveals, the WICBC had in fact invited Worrell to assume captaincy of the team against Pakistan in 1957–58, and the subsequent tours of India and Pakistan.

Worrell had declined the appointment, citing his academic studies at Manchester University, leading the Board to appoint Gerry Alexander as captain. To his eternal credit, when Worrell finally accepted the captaincy for the tour of Australia, Alexander not only happily stepped down but also served faithfully and productively as Worrell’s vice-captain on that historic tour.

Indeed, Alexander would say later, “I was tremendously delighted when (Worrell) was finally appointed captain. I thought the great injustice of my appointment against Pakistan in 1957–58 was not primarily to Frank Worrell but to Clyde Walcott and Everton Weekes.” (p 192).

Son of Grace also details a hitherto little-remembered event in Worrell’s career, when he agreed to lead an unofficial team of West Indian cricketers to tour racially segregated South Africa in late 1959. The WICBC, initially unaware of the private arrangements for this tour, was persuaded, inter alia, by a letter from Jackie Grant, former West Indies captain then working as a missionary in South Africa, and strong protestations from Sir Learie Constantine and Alan Paton, South African crusader against apartheid, to urge the hosts to have the invitation rescinded. Worrell’s motivation was, it seems, just as the later “Rebel Tour” was in 1989, the lure of better remuneration for his services and that of his colleagues. What, Baksh leaves us to ponder, would have been the repercussions if such a tour had indeed taken place?

Baksh’s book is, in fact, full of other details of Worrell’s life that, in different hands, might have seemed lurid or sensational. Worrell, it seems, apart from investing significantly in his personal appearance, had a notable penchant for strong drinks and was popular with women wherever he travelled. These may have contributed to the deterioration of his marriage. Despite his known leadership qualities and ability to mentor younger players, Worrell was inclined to seem at times remote and detached from fellow team members.

Baksh’s book is, in fact, full of other details of Worrell’s life that, in different hands, might have seemed lurid or sensational. Worrell, it seems, apart from investing significantly in his personal appearance, had a notable penchant for strong drinks and was popular with women wherever he travelled. These may have contributed to the deterioration of his marriage. Despite his known leadership qualities and ability to mentor younger players, Worrell was inclined to seem at times remote and detached from fellow team members.

Although remembered as one of the famous Three Ws of West Indian cricket during the 1940s and 1950s, theirs apparently was not always a harmonious relationship; Everton Weekes, his friend since boyhood, felt that they drifted apart in later years, and Clyde Walcott would wryly observe that he was not a pallbearer at Worrell’s funeral because he was not invited. Conrad Hunte would have been chagrined when Worrell chose to anoint Garfield Sobers, his successor, as captain over the more deserving Hunte, Worrell’s understudy on several tours.

“If we wait for the perfect time, the perfect person, the perfected self, we’ll stay frozen in an idea of love,” Elizabeth Lesser has written, “but if we fearlessly engage with the life spread out before us, we will be rewarded with a heart that can hold it all—happiness and messiness, clarity and confusion, love and loss.”

Son of Grace is the outcome of a ten-year odyssey for Vaneisa Baksh. In her fearless engagement with the life of Worrell, as presented in this biography, our esteem and admiration for Sir Frank should grow rather than be diminished in our eyes as we embrace his journey, even as she has.

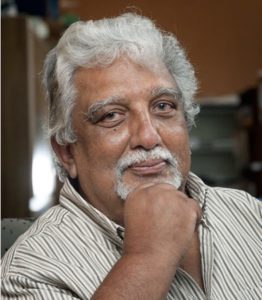

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide.