|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 3 mins

February 14, 2024

This article was first published on February 14, 1996, in recognition of Valentine’s Day.

He achieved fame as a philosopher, historian, novelist, literary and cultural critic, Marxist, politician, and lecturer. But to consider CLR James today, Valentine’s Day, is to recall that the region’s most brilliant intellectual was also very much a ladies’ man.

He achieved fame as a philosopher, historian, novelist, literary and cultural critic, Marxist, politician, and lecturer. But to consider CLR James today, Valentine’s Day, is to recall that the region’s most brilliant intellectual was also very much a ladies’ man.

Fredric Warburg, James’s publisher when he was in England in the Thirties, described him as “one of the most delightful and easy-going personalities.”

“Noticeably good-looking,” James was, “Immensely amiable, he loved the fleshpots of capitalism, fine cooking, fine clothes, fine furniture, and beautiful women, without a trace of the guilty remorse to be expected from a seasoned warrior of the class war.”

Years later, when he had moved to the US, one of James’s friends told him, “You are a man who exercises a considerable fascination over women and along with politics and what you represent there is also mixed up sexual desire and jealousy of which the women themselves are not aware.”

And yet, despite possessing this powerful sexual magnetism, he didn’t know what to do with it. His first wife, Juanita, was a beautiful Trinidadian Chinese complained to him a year after they got married, “the only time you have any pleasure with me is when you are on top of me.”

Some time around 1947, a decade and a half after Juanita lodged her complaint, his second beautiful wife Constance Webb demanded of James, “Look here, tell me what you want from me, what can I give to you.”

He didn’t know how to answer, wasn’t even sure what she meant, he later recalled, “I did not want anything in particular from her, due to my ignorance and stupidity”.

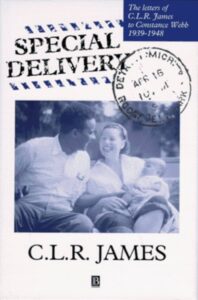

But CLR James was neither ignorant nor stupid. His was clearly more a case of say so eh do so, for as early as 1944, when he was still courting Constance with a barriage of letters, James chided her: “You are obsessed with the idea that if nothing comes of it in the end I will feel cheated, disappointed. Which proves how little you know of love. For you it is

something that you get. It isn’t. It is something that you give and gladly, that you fight to give… Accept, it is much harder than to give. If after the past year you cannot accept from me, then that is ungenerous.”

That was precisely how he didn’t treat Constance, for he didn’t know how to accept, how to let himself be loved. And yet, the strangest part of it was that, like many Trinidadian men, he never held any prejudice against women.

James’s novel Minty Alley, written before he left Trinidad in 1930, sympathised profoundly with its female protagonists. And when, much later, he became a world-renown figure, his most important intellectual collaborators were women: Grace Lee Boggs and Raya Dunayevskaya.

That was in the late Forties, he was in Reno, Nevada—a period when his love for Constance, who was in New York, burnt most brightly. Of course, ever self-conscious, he discovered all sorts of failings, including non-appreciation of her beauty:

“Sweetheart, how I have wronged you and hurt myself. Your youth and beauty, your charm and style, darling I revel in them. You are a work of art, to make me warm in my blood and delight in you aesthetically. Instead I fought you—fought your loveliness, all you had to give me as a woman. As if anything could be wrong in that. Now I have not only love and a burning glow inside of me for you but pride.”

By the time he had finished working on Notes on Dialectics with Boggs and Dunayevskaya, he felt at the peak of his intellectual powers and his passions.

“This is the man who loves you,” he promised Constance. “I took up dialectic five years ago. I knew a lot of things before I was able to master it. I knew a lot of things about loving you. I am only just beginning to apply them. I can master that with the greatest rapidity—just give me a hand. I feel all sorts of new powers, freedoms, etc., surging in me. You release

so many of my constrictions. What are you going to do? I am bursting all over with love for you.”

so many of my constrictions. What are you going to do? I am bursting all over with love for you.”

In that decade of the Forties James wrote thousands of pages of love letters to Constance, a considerable physical achievement because his collapse in 1942 from a perforated stomach had left him with shaky hands.

But by 1952, things were coming apart, and James was desperately clutching at a retreating Constance. “I see Constance often. We talk. For hours and hours at a time,” he admitted to Freddie Paine. “You thought it would be easy to get her back. Freddie, that will be the most difficult thing in the world. But that is what I want.”

The following year he was deported from the US and CLR James and Constance Webb were divorced.