|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 4 mins

“life hadn’t caught up with art, but play had to ceased to be play.” V.S. Naipaul.

By Winthrop R. Holder

LIFE may have caught up with art when armed rebels seized hostages while looters rampaged the city, sowing fields of fire in their wake.

Expressed love for country was the avowed reason behind the action, steeped in the conviction that even Allah – who knows all – and the oppressed populace were bound to support the overthrowing of the

government.

Everywhere, the events were being described as an attempted coup, but those familiar with their literature would have recognized the scenario being played out as coming straight from the pages of V. S. Naipaul:

In The Killings in Trinidad – based on the life and trials of Michael X – Naipaul had warned That “preaching oppression and easy redemption… [coupled with] the too easily awakened sense of oppression and the theory of the enemy point to the desert of Haiti.” The vicious car bombing of the police citadel and the resulting reign of terror suggests further development: Lebanon may be the next departure.

The scripts being delivered via the hostage media and elsewhere in the city streets could easily have flown off the tongues of the hysterical drug-hazy characters in Guerrillas, Naipaul’s 1975 novel: “No one here who is in charge seems to know how close this [place] is about to blow up,” says one of Naipaul’s character. Creative juices flowing and reality barely present, the character-leader of a Muslim commune – continued, “The destructive urge comes on me at times like this; I want to see fire everywhere…” Fire! Fire razed Port of Spain. Gunfire echoed all over the city. Explosions rocked the city’s heart, and buildings crumbled. Firetrucks were forced to remain motionless as the city burned. The fire was, indeed, everywhere!

But, where were the forces of security? Guerrillas provided a preview: “They say the police cracking up. Guys taking off their uniforms and running away.”

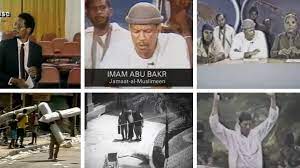

Listen to Imam Yasim Abu Bakr, leader of the band of Black Muslim fundamentalists: “That mosque is the trigger; if they pull it, Boom!” Explosions reverberated throughout the city. Guns of rage were trained on “uncaring, arrogant, and incompetent” politicians. In the streets, as security forces trained guns and eyes at the center of the city, center looters looted. Life was drained from bodies. The country was under siege.

Listen to Imam Yasim Abu Bakr, leader of the band of Black Muslim fundamentalists: “That mosque is the trigger; if they pull it, Boom!” Explosions reverberated throughout the city. Guns of rage were trained on “uncaring, arrogant, and incompetent” politicians. In the streets, as security forces trained guns and eyes at the center of the city, center looters looted. Life was drained from bodies. The country was under siege.

Another segment of the drama was played out in the backdrop of a smoldering police headquarters. As if to outdo the occupation of the Catholic Cathedral by the radicals of 1970, another section of Bakr’s band of “terrorists” stormed the immaculate Red House – a repository of the nation’s governance. Parliament was in session; civilians and ministers of Government were kidnapped. Since Trinidad has no dictatorial regime, government officials are not as well protected as in repressive societies. Suddenly, the government and nation were hostages to this shooting band of renegades.

The security forces regrouped. And the rebels who told their wives to prepare shrouds later discovered that despite their chiliastic ethos of salvation through martyrdom, they were too cowardly to die. As it were, the battle for Port of Spain raged, and a continuous trail of tears was set in motion.

In “The Killings in Trinidad,” a commune’s egocentric “leader” is described as “prime minister of himself and his little group.” Images of July’s terror flashed across the world’s screens as Bakr’s brash voice was heard around the globe. But was he ever a leader outside of his “little group” of rebels?

Guerrillas bespoke anarchy: “They don’t know who they are fighting or who they are fighting for. Everybody is a leader…there isn’t even a government.” Is the disillusionment Naipaul’s? Or was he unwittingly pointing to a stampede of the irrational? Further, should we focus on Naipaul’s condescension and overlook his contribution to understanding our conditions? Is now the time to wonder if history will absolve Naipaul?

As dusk descended on the awestruck nation, Abu Bakr, leader of “The band of terror,” ascended the dais of information dissemination and proclaimed: “The government has been overthrown… It is our good deeds which have given us victory!” Claiming support  within the military, he placed the Defense Force “under orders.” Still, where was the hoped-for support? Ponder: Is this renegade band, like Naipaul’s characters, playing out the “tragedy of simple people who think they can separate themselves from the crowd?”

within the military, he placed the Defense Force “under orders.” Still, where was the hoped-for support? Ponder: Is this renegade band, like Naipaul’s characters, playing out the “tragedy of simple people who think they can separate themselves from the crowd?”

In a New York radio interview, Raffique Shah, one of the major actors in the 1970 soldiers’ mutiny, noted that, unlike the 1970 attempt, the attack by the Muslimeen had “no organic connection with the mass movement.” If, however, the actions of Bakr and his group dramatized a popular cause, then calypsonian Black Stalin, himself a critic of the Government, may have vocalized the popular cry: “We are still depending on demonstrations, placards and the ballot box to get people out of office,” especially since “Robinson had not reached the stage of being called a Papa Doc or a Gairy.”

But now, will the government’s attempt to corral public opinion create conditions for renewed fanaticism, or worse? Or will it begin to implement humane policies to alleviate the systemic paralysis from which the horrors of July were born?

“I feel that to destroy the world is the only course of action that is now open to sane men,” says the rebel leader in the Guerrillas. As Port of Spain burned, Abu Bakr, leader of a real coup attempt, proclaimed in one of his many interviews: “This is my land, that’s why I am fighting for it,” describing the fight to save the country that almost destroyed Port of Spain.

It was easy for the leader of the Muslim commune in Naipaul’s book to be reduced to “a character,” a Carnival figure, a dummy Judas to be beaten through the streets.” But recent events were not “Carnival in July,” for “play had ceased to be play.” If art copies life in The Killings in Trinidad, then in Port of Spain today, life in its sum may well be mimicking art.

* This is a slightly modified version of an article written in early August 1990 and published in Trinidad & Tobago Review in September 1990.

W. R. (troppy) Holder, an emancipated NYC public educator and a founding member of the Caribbean Awareness Committee (N.Y.), is co-editor of BigDrumNation and the author of Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless.