|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 9 mins

February 21, 2023

Should members of a privileged enslaving family assume the moral authority to arbitrate restorative justice and the reparations cost remitted to the sons and daughters of enslaved Grenadians?

The African American scholar John Henrik Clarke warned that one should be careful of the practice of begging at the doors of the very people who made you beggars in the first place. The logical extension is that one should be aware of one’s worth and accept nothing less. I reflected on this maxim as the news emerged recently that the aristocratic British Trevelyan family acknowledged their roles in enslaving upwards of 1,000 African men, women, and children on the island of Grenada. The family, who held six plantations over the course of six generations, plans to give a public apology to Grenadians on February 27, 2023, and hand over the sum of £100,000. This amounts to less than 1 pound per living Grenadian on the island.

acknowledged their roles in enslaving upwards of 1,000 African men, women, and children on the island of Grenada. The family, who held six plantations over the course of six generations, plans to give a public apology to Grenadians on February 27, 2023, and hand over the sum of £100,000. This amounts to less than 1 pound per living Grenadian on the island.

Upon the abolition of African enslavement 1834-38 after more than a century of British and French colonialism on Grenada, the Trevelyans were among the scores of British families heavily compensated by their government. They received £34,000, $3 million in present-day currency. The newly freed ex-slaves received nothing.

The Trevelyans are today an incredibly rich aristocratic British family that amassed their wealth from the enslavement of Africans human trafficked to Grenada, where they endured deplorable and inhumane conditions of forced labor.

The narrative of the enslavement of Ottobah Cugoano, in his book Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787), provides graphic details of the gross exploitation of enslaved workers on Grenada’s plantations. And because of its horror, Cugoano’s account became a major influence in encouraging the ending of the British slave trade.

In rationalizing their unilateral and self-determined gesture of reparations, the family’s assumed spokesperson on the issue, Laura Trevelyan (head of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s New York office), admitted that “Slavery was and is unacceptable and repugnant. Its damaging effects continue to the present day. We repudiate our ancestors’ involvement in it.” At least forty-two members of the Trevelyan family have reportedly signed the apology.

But should members of a privileged enslaving family assume the moral authority to arbitrate restorative justice and the reparations cost remitted to the sons and daughters of the enslaved Grenadians? There are also broader moral questions: should the ones found guilty of a crime be allowed to fashion their own sentence, determine the penalty, and restitution cost to aggrieved victims still suffering from these well-documented crimes against humanity? Of course, other important questions can be proffered regarding the quality and quantity of restorative justice, forms of payments, etc. Are monetary reparation and a pledge of atonement even measurable compensation for the crucible of slavery and lives lost due to the enslavement enterprise?

The rationalization for reparations for over a century of enslavement in Grenada is rooted in the belief that chattel slavery was a terrible crime against humanity. And that those enslaved and their descendants today are entitled to compensation for the harm done to them. And this is recognized by international law.

This compensation could take many forms, including financial payments, educational opportunities, institution-building, individual and social therapy, a combination of these, and other forms of support.

This compensation could take many forms, including financial payments, educational opportunities, institution-building, individual and social therapy, a combination of these, and other forms of support.

Although monetary compensation is often mistakenly regarded as the sole form of reparation, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, offers a much more substantive and respectful portrait.

“Measures taken to address the past should seek to transform the future. Structures and systems… designed and shaped by enslavement, colonialism, and successive racially discriminatory policies and systems must be transformed. Accordingly, reparations should not only be equated with financial compensation. They also comprise measures aimed at restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition, including, for example, formal acknowledgment and apologies, memorialization, and institutional and educational reforms.”

While many Grenadians seem to be satisfied and even happy with the news of the Trevelyans’ hollow gesture of supposed reparation, there are others, this writer included, not pleased with the principle and sum attendant with the “apology.” Nevertheless, the tepid acknowledgment by the heirs of a former slave-owning aristocratic family is their concession to unrelenting and growing global movements for reparations and the exposure of previously hidden enslavement ties. We must continue the struggle to shape Grenada’s reparations agenda and not allow anyone, especially those who benefited from our fore-parents suffering, to set it for us.

Credit must be given to relentless struggles by generations of reparations activists within the African Diaspora, Rastafarian communities, and the Caricom Reparations Commission, whose 10-point agenda has provided research resources, a united approach, and continues to impact the debate.

The Black Lives Matter Movement significantly boosted the reparations momentum (BLM) sparked by the tragic racially motivated killing of George Floyd. This led to international outcry and actions seeking to address visible institutional vestiges of racialism, colonialism, and other pillars of white supremacy globally.

This medal has traditionally been bestowed and worn by Governors-General across the Commonwealth, who the British Monarchy has knighted.

The results of BLM’s anti-racist activism and consciousness-raising can also be seen in public exhibitions and the ‘coming out of the closet’ of many institutions. This was also attendant by deepening debates about the legacies of enslavement and open challenges to the prevailing presence of white supremacist icons in the public sphere. BLM activism also sparked challenges to colonial relics, such as the lapel worn by the Governor General in many former colonies, including Grenada, with a racist depiction of a black man being trampled by a white archangel.

Public education initiatives, such as the exhibition “Slavery & the Bank” at the Bank of England Museum in London, revealed some of the deepest, darkest secrets of the enslavement period. Such events placed the spotlight on the inter-relationship between the Royal Family, generations of British aristocrats (such as the Trevelyans), the international banking system, and state institutions (including the Royal family) during the enslavement enterprise.

The Bank of England, Britain’s largest and most influential institution, itself was exposed. The bank owned 599 enslaved people on two plantations in Grenada, Chemin (in the Hopevale area of St Georges) and Bacolette (in the parish of St Davids). Individual Bank of England governors owned a further 722 enslaved sufferers in Grenada. Not surprisingly, the British monarchy itself, beginning early in the 18 century, was involved in Grenadian slavery, having shipped the most enslaved Africans to Grenada.

Ironically, Grenadians and their descendants (and others from the Caribbean) were shocked to find out in an official Tweet that, while paying their taxes up to 2015, they were helping to pay off compensation to the slave-owning families who owned their ancestors. This continued the British state’s payment of the £20 million (17 billion today) debt to their Caribbean enslavers, the virtual British state ‘reparations’ to the Caribbean enslavers.

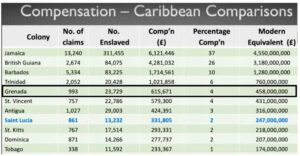

Of this £20 million, the British treasury issued 993 claims for British enslavers with holdings in Grenada alone, amounting to £615,671, the modern equivalent of US$551 million. In a recent interview, Laura Trevelyan revealed that in 1835, the Trevelyans received about £34,000 for losing their “property” to ‘freedom’ in Grenada (equivalent to about £3m).

Of this £20 million, the British treasury issued 993 claims for British enslavers with holdings in Grenada alone, amounting to £615,671, the modern equivalent of US$551 million. In a recent interview, Laura Trevelyan revealed that in 1835, the Trevelyans received about £34,000 for losing their “property” to ‘freedom’ in Grenada (equivalent to about £3m).

As the BLM and global activism coalesced, institutions such as the Church of England and the Archbishop of Canterbury have apologized for their historical links to the slave trade and the “great dismay” and “shameful and horrific sins” these institutions have committed “during the horrific trade in people in Grenada and the rest of the Caribbean.” And most recently, though absent of any concrete promise of reparations, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologized on behalf of his government for the Netherlands’ historic participation in slavery and the slave trade in the Caribbean and further afield.

In his book, “How Britain Under-developed the Caribbean,” Hilary Beckles, Chairman of the Caricom Reparations Commission, reminds us that “Royalty, aristocracy, and government were aligned in the strategy of African enslavement. … The plantation system was more than an economic institution. It was also a social culture with a distinct race-based ideology that gave white colonial elites power over all others, with no accountability.”

The primary source documents make clear the value of a relatively small territory like Grenada to the enrichment of the British ruling classes, the colonial state, and the British empire. And how Britain, to borrow a title from Walter Rodney and later Hilary Beckles, under-developed Grenada. For example, it was revealed that throughout the 1780s, the Bank of England received a regular income from the Grenada plantations and gradually bought up the shares of the other creditors leading to full possession from the late 1780s until the early 1790s. This, in turn, helped the Bank to eventually maximize its profits, selling the Chemin and Bacolette plantations and its enslaved persons at a premium in the late 18 century.

The aristocratic family’s reckoning with their past must have been prompted by the exposure of details of the history of slavery that have become more apparent by more in-depth research and the emergence of widely shared databases such as slave voyages.com, enslaved.org, that have emerged from major universities around the world, including the University of the West Indies, Oxford, Cambridge, etc. The latter two institutions themselves were held to account for their enslavement practices. There is some parallel between the recent exposure of these records of African enslavement through these databases and research and the impact that enslavement narratives such as Ottobah Cugoano’s had leading up to abolition.

And the Caricom 10-point agenda on reparations provides a concerted institutionalized approach to addressing the quest for reparations worldwide on behalf of the Caribbean. In coming to terms with her family’s atrocities in Grenada, Laura Trevelyan said she “…hope[s] that [they’re] setting an example by apologizing for what [their] ancestors did.”

As part of this agenda, Laura Trevelyan believes it is also essential that the voices of “those who have been affected by slavery are heard and that the legacy of slavery is acknowledged and addressed.” The apology and the £100,000 ‘reparations’ will be ‘formally’ conducted in a public event at the Grenada Trade Center in St Georges on February 27, 2023.

Laura Trevelyan claims that no living member of the family was aware that the source of the family’s wealth was derived from the enslavement of over a thousand Grenadians. This is an incredible admission considering that she is a skilled journalist and a reputable researcher who wrote the definitive history of her family in her 280-page book, “A Very British Family: The Trevelyans and Their World.” The family’s patriarch, Charles Edward Trevelyan, is despised by many Irish for his crimes against humanity there during the “Great Hunger” in 1847.

Grenada should accept the Trevelyan apology as a good faith and encouraging gesture. But it must be recognized as piecemeal. The £100,000 should be accepted as a critical juncture in our local reparations conversation.

We should be careful, however, to keep John Henric Clark’s caution in mind and not diminish our worth as human beings who are descendants of and current legacy victims of internationally-recognized centuries-long crimes against humanity. We must remind the Trevelyan aristocrats that we are as worthy as they are of dignity, equity, justice, and human rights.

The Grenadian people should be the ones with the ultimate determinants of any reparatory process. The February 27 meeting with Laura Trevelyan should begin a series of town hall meetings on the issue nationwide. At the end of this process, some form of agreement on a Grenadian procedure for reparatory justice would occur.

So what can real reparations look like?

One possibility of the Grenada reparations option is that the family, in conjunction with the Bank of England and other families who were enriched from Grenadian slavery, will establish a modern, well-equipped Grenada Heritage District. Like the Barbados plan, this site will be dedicated to the history of enslavement in Grenada and its enduring traumas. Attendant to this recommendation could be the legal stipulation that Britons with financial interests in slavery, the Bank of England, etc., would fund and maintain this institution for the next 200 years or commensurate with their involvement in Grenadian enslavement.

But there are other p ossibilities of reparative justice in this context, money being only one aspect of a multi-pronged agenda. Another option could have UK benefactors of Grenadian enslavement build a well-equipped, state-of-the-art, modern hospital in the country. This could be built in the Bacolette or Hope Vale area, the site of the erstwhile plantations owned by the Bank of England, and the location of much of our ancestors’ physical and psychological pain.

ossibilities of reparative justice in this context, money being only one aspect of a multi-pronged agenda. Another option could have UK benefactors of Grenadian enslavement build a well-equipped, state-of-the-art, modern hospital in the country. This could be built in the Bacolette or Hope Vale area, the site of the erstwhile plantations owned by the Bank of England, and the location of much of our ancestors’ physical and psychological pain.

Such measures are two possible ideas that can go a long way in beginning to repair the harm done to our people and as a means of adequate, effective, overdue restorative justice. The Trevelyan and other families should also see this as mutually beneficial. They can gain respect as the first family to have taken this brave step of making concrete amends for Caribbean plantation atrocities. And this won’t exact much of their current wealth, especially with the possibilities of tax write-offs.

Anything short of legal, substantive, institutional commitment from the Trevelyans in these conversations would be tantamount to accepting trinkets of beads for the hundreds of thousands of descendants of Africans who have suffered on Grenadian plantations.

The acceptance of less than 1 pound per Grenadian risks reducing our people to the caricatures the colonists depicted in Eurocentric accounts of the historic first encounter on our islands — begging at the doors of the very people who relegated us to mendicants in the first place.

Martin P. Felix is an educator, researcher, and writer. This article is extracted from a lecture delivered on February 17, 2023, on the Policy as Possibility Panel, 13th Annual African, African American, and Diaspora Studies (AAAD), Interdisciplinary Conference, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia.