|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 5 mins

January 31, 2023

“[A] conversation with him… was a learning experience… on which he would bring to bear his perceptive literary skills [and] his vast range of interests in many things: cricket, calypso, politics, carnival, art, and international affairs would somehow become interrelated in a conversation that might have begun with a question or comment about the merits of crab and callaloo as a symbol of [our region]”.

There will be many tributes to Gordon Rohlehr, from those far more competent than I, those who knew him in his professional life and/or personal life and are far more qualified to offer the words appropriately suited to celebrate a man whose career and published work earned him iconic status in the interrelated worlds of literature, culture and social discourse. I can only offer a personal salute to someone with whom I was singularly fortunate to have shared space in one way or another over the course of 45-plus years and whose influence on the way I have approached my own life has been persistent and profound.

I arrived at UWI St Augustine in 1968 straight out of St Mary’s College, the metaphorical blank page on which so much remained to be written. In that first year, Gordon Rohlehr, who had come to the campus the year before, was our lecturer for several books on the course then titled Introduction to English Literature. And, in the confines of the Arcon Lecture rooms north of the campus, my fellow students and I listened in rapt attention as we were introduced to textual and stylistic subtleties of which we had little or no previous inkling as we explored Conrad’s Nostromo, Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Mais’s The Hills Were Joyful Together and, most importantly for me at least, Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas. In between, he introduced elements of the Folk in West Indian Literature, of which calypso was a key part.

Quite apart from the tolerance he exhibited with what were the naïve assumptions and ways of interpreting literature with which so many of us had arrived, he brought as well a broad and equally deep range of insight and connections into and a

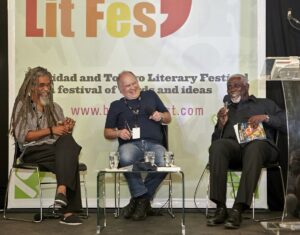

Literary scholar and cultural commentator Dr. Gordon Rohlehr at Trinidad and Tobago’s Bocas Literary Festival

cross a vast array of world literature, current events, and social and political affairs at home and internationally. It was a feature of his approach in my second year as well when he explained the intricacies of John Donne and the Metaphysical poets, the revolutionary tenor of Marlowe’s Faustus, the economic impulses behind love and marriage in Jane Austen’s novels, and the social dystopia that permeated the work of Charles Dickens.

That scope of scholarship was complemented by a constant readiness to engage in conversation beyond the classroom, whether on the corridors of the new JFK buildings on campus that opened in 1969, in the quadrangular expanse that interconnected them, or later over the telephone. A conversation with him, as so many others have noted, was a learning experience of its own, on which he would bring to bear not only his perceptive literary skills but his vast range of interests in many things: cricket, calypso, politics, carnival, art, and international affairs would somehow become interrelated in a conversation that might have begun with a question or comment about the merits of crab and callaloo as a symbol of the West Indian melting pot.

The early seventies were heady times on campus and in the wider society, and Rohlehr’s writings at the time often occupied several pages of Tapia or appeared in other publications dedicated to West Indian affairs. I remember, in particular, a critical dissection of Eric Williams’s From Columbus to Castro that caused raised eyebrows in many circles for daring to dispute the Great Man’s version of West Indian history and finding fault with its scholarship. These writings would form the basis of the collections he would put together some years later in life, a process in which I would be fortunate to play some small part.

Personal events in my own life led me to miss most of my third and final year on campus in 1970-71; I had also not signed on to his introductory course in West Indian Literature, opting for the Chaucer era instead, but like many others, whenever I had the opportunity, I would sneak into his lectures, especially in the early ones on calypso and the oral tradition in West Indian Literature. As luck would have it, however, when I returned to UWI some twenty years later to complete the formal requirements for the award of a degree (and was mandated to redo the entire programme), the West Indian Literature programme had become much more established, with a broader range of texts and authors, allowing me to compensate fully for the choice I had made twenty years previously.

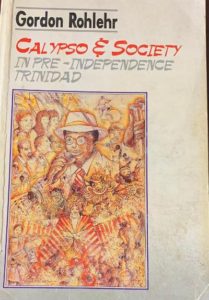

By this time, Rohlehr had already published his magisterial work, Calypso and Society in Pre-Independence Trinidad, and was beginning to put several of his essays

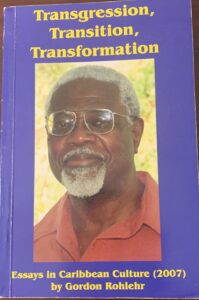

together in collections, several of which I published on his behalf over the years, beginning with My Strangled City in 1992, and ending ultimately with Transgression, Transition, Transformation in 2007. I also tried to get him to republish Calypso and Society in an updated version, larger format, with more pictures, and including analysis of calypsos of the 50s and 60s.

together in collections, several of which I published on his behalf over the years, beginning with My Strangled City in 1992, and ending ultimately with Transgression, Transition, Transformation in 2007. I also tried to get him to republish Calypso and Society in an updated version, larger format, with more pictures, and including analysis of calypsos of the 50s and 60s.

He wisely demurred; we did reprint the book, but only in its earlier version. I would also secure his involvement in what I think was the first compilation of oral and related poetry, Voiceprint, which was published by Longman UK in 1989 but has sadly gone out of print. He wrote and self-published Pathfinder in 1981, which is still the definitive guide to Edward Braithwaite’s trilogy, The Arrivants, and published subsequent essays on Braithwaite’s later work.

He was an ardent cricket fan; we would have long conversations over the telephone discussing the performances of the West Indian team as its fortunes declined, and he would often have his own unique way of placing those performances in a wider social, political, and economic context, even as he discussed bowling and batting technique. He played a bit himself, although I only saw him bowl leg spin in the nets; I believe he may have once been a medium-pace bowler earlier in life.

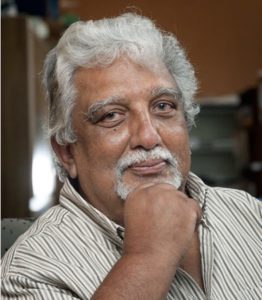

In the 45 and more years I knew Gordon Rohlehr, I never saw him angry. There was always a smile that greeted you whenever he saw you and a chuckle that rumbled intermittently from deep within as conversations progressed. Despite his impressive credentials and resume, he never seemed to lose the common touch; he would chat easily with friends in my company whenever we met, despite never having met them. He became a favourite of my employees at Lexicon Trinidad whenever he visited, who admired his simple, straightforward manner and his unfailing courtesy to them.

On a Sunday on which I was also to learn of the tragic death of a distant relative, I felt the world stop still for a moment when I learned of Gordon Rohlehr’s passing. Perhaps it really did; Shakespeare has told us that the heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes. I can only imagine Gordon chuckling and shaking that massive frame of his were he to read such a massive impertinence on my part.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Mark of Cane, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Mark of Cane, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

What an elegantly written piece. It brings the authenticity of the man to one’s navel.