|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 11 mins

January 23, 2023 (Originally published on March 20, 20217)

In 1977, a calypsonian from Trinidad & Tobago named the Mighty Unknown caused patrons of the calypso tent to fall off their seats when he performed a calypso called “Ah Vex.” Unknown, in his cleverly constructed offering, threw four stanzas of piccong at the St Lucian poet whom the calypsonian alleged had had the temerity to be critical of the place which had been good enough to extend to him, its generosity;

“Derek you must be fou bé dangé or mad

Sit down on river stone and talk river bad

You wouldn’t talk about we pitch lake, oil and sugar

That you have enjoyed, through we ancestor;

What about we multi-racial society

Who are so friendly and full of courtesy,

Carnival is we festival and commerce

And sex is ah must; through the universe

You see why ah vex, ah more than vex

Derek Walcott say Trinidad is Carnival and SexAh vex! Ah s-s-s-stammering vex

Derek suffering from one big, big, big complex

Derek go back to St Lucia and you would see

All kinda vice and sexology

Man marrieding man and is tee-la-lee-lah

And Derek wouldn’t say ah thing about St Lucia.”

Unknown was selected for the National Calypso Semi-Finals that year, and his composition, beyond its triggering of the nerve of sensibility in a population fiercely protective of its new-found nationalism in that post-black power era, would have made the average Trini, sadly, just barely aware of the genius that literally walked and worked amongst them.

Walcott had lived and wed and wrote and worked in Trinidad & Tobago. The Mighty Unknown must have been on hand to over-hear one of the programs, like “Cultural Miscellany,” that was state-sponsored and frequently aired on one of the two radio stations that operated then. Walcott would, at the time, have been a regular contributor in the same way that he had regularly contributed to one of the daily newspapers with his regular features. There was, therefore, an awareness of his presence here, an awareness that prompted Unknown’s indignation at the poet’s need to bite the hands that were feeding him;

“Derek you must be fou bé dangé or mad

Sit down on river stone and talk river bad…”

Perhaps the 1977 episode, though, was an aberration in the defining of the relationship betwixt the Nobel Laureate and the Trinidadian, for everything that this writer grew to learn and to know about the man Derek Walcott during the next forty-odd years signaled attitudes and emotions that were extremely contrary to those provoked by Julian Pierre’s singing in the mid-nineteen seventies.

There was respect, admiration, love, and hero-worship, in some cases notwithstanding the brusqueness of attitude that Walcott displayed periodically when he felt that his colleagues fell short of his expectations. But, much of this came later.

Our first official “meeting” came when as a first-year, part-time student of West Indian Literature at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine, the vacation assignment was – over Christmas – writing a book report of the Walcott anthology, “In A Green Night” (1962).

The crispness in his presentation of successive lines of soul-touching poetry was fascinating. The subsequent satisfactory grade for the Yuletide exercise further encouraged and heightened the interest in the man and his work. By the culmination of the semester, there was another student admirer of the craftiness of the magnificence of the poet’s use of the idiom.

In my teenage years, I met VS Naipaul and enjoyed the images presented in the mirror. Titus Hoyt, Man Man, Hat, and Laura—characters from a collection set in wartime Trinidad–were real. I knew them. They lived in the yard in which I grew up in Boissierre Village No. 1. I had not, however, analyzed and joked at their frailties until the writings of Vidiadhar Surajprasad had skinned and presented them for further examination….. as the pathologist would do to a patient etherized upon a table. Within a few years, I was also to meet Ganesh Ramsay Muir and Mohun Biswas—the principal characters in two novels by VS Naipaul. Their narratives were engaging and enjoyable in the comic sense, and the tragedy was spiced with dashes of comedy.

Walcott, when I met him, triggered no laughter. The seizure was different. The language of the poetry was compelling. One marveled at the range and the depth of the imagery. And the messages resonated right off the galvanized fence in my backyard. They were localized, and they teased and awakened my curiosity. I did not need encouragement, therefore, nor prompting, nor another Home Work exercises to find the SPCK Bookshop on Abercromby Street, Port of Spain, and begin to peruse my next two anthologies; first “The Castaway” (1965) and then “The Gulf” (2004).

The growth of a quiet admiration was sustained, even as I read some more. Walcott seemed to understand – and if he did not understand, appeared to be giving voice to a common struggle.

Almost all of my colleagues in that primary year at St Augustine had given up. Walcott was too abstract; they said….inaccessible! I found their disenchantment and rejection of the poetry painfully disappointing, but I could not blame them entirely when they opted for Second Year Sociology or Second Year Government. I begged to differ and lost a few friends, for regular paths became separated by the dictates of the timetables. Their rejection of Literature was absolute….as absolute as my resolve to continue. Sure, not everything was grasped at the first or even the second reading sometimes; but in the lines and the language, there was so much joy – not laughter, nor ridicule; but joy in the pure aesthetics of what the lines contained. I have had no regrets…

“An old lady writes me in a spidery style

Each character trembling, and I see a veined hand

Pellucid as paper, travelling on a skein

Of such frail thoughts its thread is often broken;

Or else the filament from which a phrase is hung

Dims to my sense, but caught, it shines like steel,

As touch a line and the whole web will feel.”

(A Letter from Brooklyn, 1962)

Additionally, works like; “A Far Cry from Africa,” “The Hurricane,” “Hic Jacet,” “Codicil,” “The Castaway,” “Almond Trees,” and “The Gulf” addressed troubling, personal and universal issues – seemingly within a microcosmic universe that, for a young student of the language, was Trinidadian. Walcott appeared to be grounded within the country and to have a predilection for the things that concerned us here.

Black consciousness in the era immediately after 1970, negritude, colonialism, patriotism, the crisis of identity – his and ours, the brain-drain, the impact and the effects of/on the natural environment, the sea, the exodus to North America, theism, death, the weather……even my fear of flying! – All his themes seemed to reflect my concerns. Walcott became personal. I did not – could not perhaps, go as far, but many, many times, we journeyed along the road together. Line after line of his images was “home-grown”-

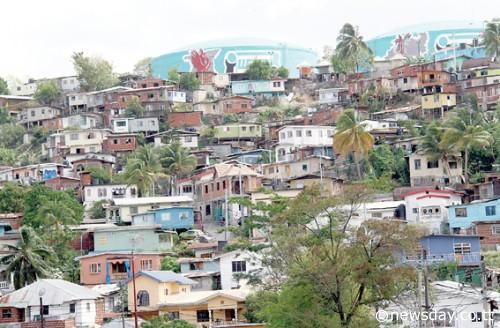

Laventille: “To go downhill from here was to ascend.”

“How can I turn from Africa and live?”(“A Far Cry from Africa”

“At Cedros, thudding the dead sand

in spasms…” (Tarpan”)“Bethel and Canaan’s heart

Lies open like a psalm…” (“Crusoe’s Island)“Above the beached, rotting pirouges,

They were venomous beaked clouds at Charlotteville.” (“Codicil”)“Dusk. The Flight, Passing Blanchisseuse.

Gulls wheel like from a gun again,” (“The Flight”)And, how could I not but personalize his (or is it my) “Laventille”?

Laventille: “To go downhill from here was to ascend.”“It huddled there

steel tinkling its blue painted metal air,

tempered in violence, like Rio’s favelas,

with snaking, perilous streets whose edges fell as

its Episcopal turkey-buzzards fall

from its miraculous hilltop

shrine,

down the impossible drop

to Belmont, Woodbrook, Maraval, St Clair

that shine

like peddlers’’ tin trinkets in the sun.”

Derek Walcott

The description is impeccable. The imagery is unique. The style is mind-boggling in its accuracy. Even the presentation of the lines on the page is reflective of the ‘unharmonious’ nature of the terrain.

Walcott continues;

“…where the inheritors of the middle passage stewed,

five to a room, still clamped below their hatch,

breeding like felonies,

whose lives revolve round prison, graveyard, church.

Below bent breadfruit trees

In the flat, coloured city, class

Escalated into structures still,

Merchant, middleman, magistrate, knight. To go downhill

From here was to ascend.

The middle passage never guessed its end.”He writes this for VS Naipaul, Trinidadian novelist. And for the university professor, another Trinidadian, Kenneth Ramchand, Walcott writes, “The Saddhu of Couva”–

“And to that gong

sometimes bald clouds in saffron robes assemble

sacred to the evening,

sacred even to Ramlochan

singing Indian hits from his jute hammock

while evening strokes the flanks

and silver horns of his maroon taxi,

as the mosquitoes whine their evening mantras,

my friend Anopheles, on the sitar,

and the fireflies making every dusk Divali.”

The imagery is precise, and like the painter with a skillful hand and accurate eye, the language captures and presents the detail of the scene with fantastic flawlessness.

The next magical piece selected to make the point evokes that Trinidadian calypsonian who, above all others, fascinated listeners with fantastic tales from his boundless imagination. The singer and his genre are both Trinidadian. As if to complete his trilogy of references and assist in emphasizing this writer’s argument, Walcott selects for its dedication, Earl Lovelace – the Trinidadian novelist…

“I have a room where I keep a crown,

And Satan send me to checkout this town.

…I beg him two weeks’ leave and he send me

back up, not as no bedbug or no flea,

but in this limeskin hat and floccy suit,

To sing what I did always sing: the truth.

Tell Desperadoes when you reach the hill,

I decompose, but I composing still:”

The style is rhythmic. The language is ‘calypsonic’ and almost pedantic. The message is savagely brutal, ay, akin to political rhetoric…..”lyrics to make a politician cringe” (“Calypso Music”, David Michael Rudder—1987).

“The time could come, it can’t be very long

when they will jail calypso for piccong,

for first comes television, then the press,

all in the name of Civic Righteousness;

it has been done before…”

“…rumour can twist

Into a style the local journalist –

As bland as a green coconut, his manner

Routinely tart, his sources the Savannah

And all pretensions to a native art

Reduced to giggles at a coconut cart,

Where heads with reputations, in one slice,

Are brought to earth, when they ain’t eating nice;

and as for local Art, so it does go

The audience have more talent than the show.”

“Is Carnival, straight Carnival that’s all

the beat is base, the melody bohbohl,

all Port of Spain is a twelve-thirty show,

some playing Kojak, some Fidel Castro,

some Rastamen, but, with or without locks,

to Spoiler is the same old khaki socks,

all Frederick street stinking like a closed drain,

Hell is a city much like Port of Spain…

and Lord, the sunlit streets break Spoiler’s heart,

to have natural gas and not to give a fart,

to see them lineup, pitch-oil tin in hand:

each independent, oil-forsaken island,

…but from Jamaica to poor Dominica

we make them know they begging, every loan

we send them is like blood squeezed out of stone,…

and, more we give, more we congratulate

we-self on our own self-sufficient state.

In all them project, all them Five-year Plan,

what happen to the Brotherhood of Man?”

(The Spoiler’s Return”, 1981)

The poetry was not all.

I met and read the plays and, in a sense, the poetry again. There were lines of drama that were poetic in their expressions!

“Well I was coming through the forest now

And I passed by the white spring, and I saw

Some poor souls going to work for the white planter.

He’ll work you like the devil, but that’s what you want,

You and your impatience and arm cast in iron,

So turn to the right, go through the bamboo forest,

Over the black rocks then the forest will open,

And you will see the sky, below that a valley,

And smoke, and a white house that is empty,

The old fellow is hiring harvesters today” (Ti Jean and his Brothers, 1985)

And all of this…all of my encounter with Walcott, so far, has been within the twin island republic of Trinidad & Tobago. Walcott stood, for me at least, like a Colossus;

“I’ll be what I am, so to hell with you. I’ll be what I am. I drink, and I drink and I feel nothing. Oh, I lack heart to enjoy the brevity of the world [The FIREFLY passes dancing] Get out of my way you burning backside. I’m the prince of obscurity and I won’t brook interruption! Trying to mislead me because been drinking. Behave, behave. That youngster is having a terrible effect on me. Since he came to the estate, I’ve felt like a fool. First time in me life too. Look just a while ago I nearly got angry at an insect that’s just a half-arsed imitation of a star. It’s wonderful! An insect brushes my dragonish hand, and my scales tighten with fear” (Ti Jean and his Brothers, 1985)

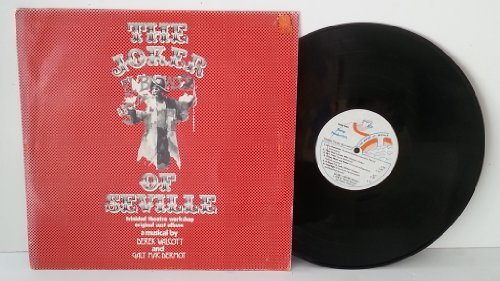

I was fortunate, as a young man, to see “Dream on Monkey Mountain,” “Ti Jean and His Brothers,” “Beef No Chicken,” and, of course, “The Joker of Seville.”

The latter drew me to Woodbrook; three or maybe four times, in 1974 when Walcott’s poetry and his prose, emerging from its Spanish antecedents and harmonizing itself with the music of Galt Mac Dermott was to fill the cramped interior of The Little Carib Theatre night, after night, after night as the patrons’ insatiable desire for the jousts of bodies and language awakened in Trinidad & Tobago a universal desire for the theatre.

The front sign of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop. May 7th, 2015.

Notwithstanding an understanding of the many components that must interface to have the drama going, one must acknowledge the genius of Walcott – conductor on the bandstand – in his ability to draw citizens from all parts of the country for the exhilarating performances. It was undoubtedly the single occasion when Walcott’s poetry, unlike the commentary I had heard so many times before, was accessible to all.

The drumming of Andrew Beddeau, Syd Skipper’s crooning, Mac Dermott’s harmonies, Hamilton Parris’s sobriety, and Nigel Scott’s chicanery; within their various roles have etched for all-time notes of pleasure that regularly surface on the landscape of memory.

Whilst it is true that Galt Mac Dermott and Syd Skipper and Helen Camps, and Wilbert Holder might not have been the Trinidadians in the team, Walcott’s direction then, like with other presentations before and after the Joker, brought to the fore some of the best that the country has had to offer in the realm of theatre performance.

One saw the magnificence of the troupe as a reflection, not only the writing, but the vision, direction, and passion of the father of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop….and, perhaps, in a real way – the Father of Trinidad & Tobago Theatre!

The front sign of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop. May 7th, 2015.

Walcott’s labour of love had culminated in the Joker of Seville into an amazing gestation, and the offsprings were; Hamilton Parris and Nigel Scott and Norline Metivier and Pat Flores and Errol Jones and June Nathaniel and Andrew Beddeau, and like the others before and after, they had morphed their craft and their talent – where it did exist – into perhaps the finest dramatic scenes that the country has known.

Walcott’s raison d’etre, is perhaps best explained in “Hic Jacet”;

They’ll keep on asking why did you remain?

Not for the applauding rain

of hoarse and hungry thousands at whose centre

the politician opens like a poisonous flower

not for the homecoming lecturer

gripping his lectern like a witness, ready to explain

the root’s fixation with earth

nor for that new race of dung beetles, frock-coated, iridescent

crawling over people.

Before the people became popular

he loved them” (“The Gulf and Other Poems”, 1969)

Derek Walcott founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and remained here, maybe because he loved us…or maybe, he felt that he was one of us.

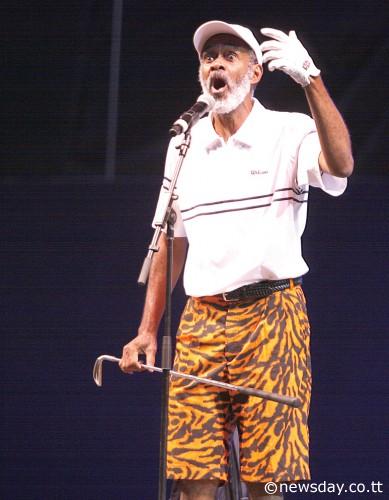

Llewellyn Mac Intosh, a free-lance radio broadcaster and a calypsonian (Short Pants) who practices his craft in Trinidad & Tobago, is a retired secondary school principal who currently spends his time supporting the provision of educational opportunities for socially disadvantaged young men in the twin-island republic.

Llewellyn Mac Intosh, a free-lance radio broadcaster and a calypsonian (Short Pants) who practices his craft in Trinidad & Tobago, is a retired secondary school principal who currently spends his time supporting the provision of educational opportunities for socially disadvantaged young men in the twin-island republic.