|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 26 mins

January 7, 2023 (First published in Trinidad and Tobago Review, October 6, 2008).

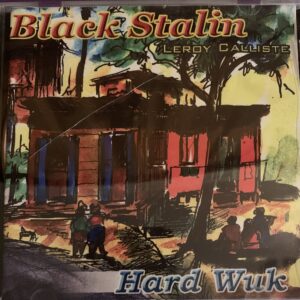

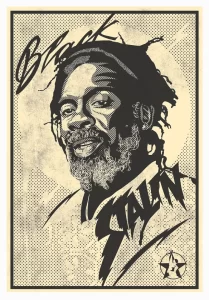

A Wide-Ranging Appreciation Of Black Stalin’s ‘Hard Wuk’ (PART TWO)

“It’s important to see us through our language…. When I say our language, I mean our Resistance English. [Our] music is for the world but, again, through our eyes.” – Black Stalin, 2001

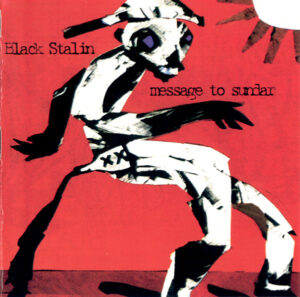

Commenting on Spice islander talkshop–which approximates a public university where everyone is both student and professor–Bigdrumnation asserts, “Stalin conferred on Brother Valentino the title of ‘People’s Calypsonian’ [and] Stalin lavished tributes (in song)… on panist Winston ‘Spree’ Simon, and chutney singer Sundar Popo.” Just as Stalin forged and valued lifelong friendships with the “Sufferers” for whom he spoke, he also treasured and nurtured artistic relationships. Indeed, his epic “Sundar” was a call to national unity and, more importantly, to the indomitable Sundar Popo. Writing Sundar into Kaiso lore and our cultural history Stalin sang:

Popo.” Just as Stalin forged and valued lifelong friendships with the “Sufferers” for whom he spoke, he also treasured and nurtured artistic relationships. Indeed, his epic “Sundar” was a call to national unity and, more importantly, to the indomitable Sundar Popo. Writing Sundar into Kaiso lore and our cultural history Stalin sang:

Since de days of Nani and Nana

He is de man who really start chutney

And clear de way for Rikki and Drupatee

So now I going and do for you ah chutney jam.

On Sundar’s passing, Hinduism Today reported that Stalin “delivered the eulogy at Sundar’s funeral, becoming the first Black artist to speak at the funeral of a Hindu/Indian…” The paper captured Black Stalin in full flight. It underscored Stalin’s humanity and commitment to crossing borders to ignite social cohesion among “sufferers.” The article noted, “[i]t was a touching ceremony to see a Black calypsonian among the many orthodox Maha Sabha pundits who performed the religious rites for Sundar Popo.” Highlighting the depth of the friendship, the publication historicized Stalin’s presence thus: “Stalin sang the 1995 song he and Sundar had sung together on the national calypso stage.”

Indeed, The Black Man, like David Rudder’s The Ganges and The Nile, commits to spreading the gospel of unity and oneness while documenting “The Autobiography of the Now.” Furthering his admiration and celebration of artists, Stalin collaborated with Roy Cape, the famed bandleader, to pay tribute on the playful “Leroy, Roy,” in which Stalin sings: “Since you is a kaisonian, take the mike and let we extempo.” But, instead of taking the mic Roy Cape takes his sax and obliges with a hauntingly magnetic impromptu solo; all the while, The Black Man ‘bigs up’ the legion of musicians who influenced Cape. “Leroy, Roy,” then, is a tightly constructed and arranged ode that only skilled musicians could conceive and execute flawlessly. Yet there’s tension in the piece as the chorus encourages the mock duel instructing the ace saxman to “Blow Roy Cape” as he continues to provide sweet music for Stalin and us all. The zenith of collaboration!

Similarly, highlighting deep and genuine camaraderie, Stalin reveals, “When [U.W.I. announced the degree,] one of the first calls I got was from Gypsy… but I wasn’t home. So he [left a voicemail]-two impromptu verses… expressing how beautiful he felt about the recognition.” And when I asked Short Pants, another master of the extempo, and host of Kaiso Kafe, for a reaction to the news, he obliged:

“It is fitting that we celebrate/ The Caribbean Man gets the Doctorate.

His Immortal Message still there to see/ The Black Man, Doh Get Nothing Easy –

But We Can Make It If We Try/ We can Bun Dem if we hold we head high.

Feel to Party; Better Days Coming/It’s the time to Play One for Black Stalin!”

Such quick recall and condensed presentation in verse of Black Stalin’s discography highlight the Black Man’s awe and confirm that many of his titles are catchphrases that capture our indignation and imagination as they register deeply in our consciousness. And, amplifying Short Pant’s verse, The Black Man continued his reflections: “And calypso people and associations from all over the Caribbean and as far as Britain, even ordinary people called to congratulate me.” Stalin’s music, sometimes received as therapy, has touched people from many walks of life.

Eddy Taylor, then, a NY-based, retired hospital administrator from San Fernando, reflected, “We began to recognize that intellectually, the Black Man had more to offer than purely the jump and wave party mentality.” He adds, “although the calypsonian was always the messenger, Stalin built on that tradition by fusing and channeling the bacchanal situation and the entertainment arena into a focus on social commentary and used our common, everyday language and behavior to raise our level of psychological and political consciousness.” The key to Stalin’s reach and his mode of instruction is an ability to cultivate the intellect of the downtrodden and the dispossessed by forcing us to revisit and re-engage deeply troubling and formerly suppressed issues. The Black Man pushed people to consider and talk about things they may not necessarily want to confront and talk about.

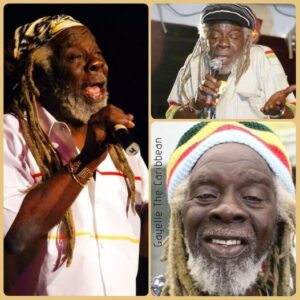

King Swallow, multiple Antiguan Calypso Crown and Road March Title winner who was honored at the October 25 (2008) Annual Sunshine Awards (N.Y.), testified to The Black Man’s appeal and influence in the international calypso community: “If you ask him about Rupert Philo he’ll tell you, ‘That’s my brother. I have a brother in Antigua.’ It’s always an encouraging feeling to go and watch him perform. Sometimes if I’m going on stage before him, he’d say, ‘I’m going to take you in.’ And, I make sure that I’m out of the dressing room to take him in when he’s on stage…. He’s always accepted in Antigua as one of the greatest performers…. He does it so well and so easily. You can even say he is flawless…. Over the years, his work has strongly influenced my work: In composing, the artistry, the presentation of the music, his stage personality in all these aspects, Stalin is super.”

As such, the calypso fraternity from far and wide welcomed this honoring of Black Stalin as only the second calypsonian to be recognized by the university with an honorary doctorate! Interestingly, at the July 2008 International Conference of the Association for Cultural Studies held at Mona, Jamaica, David Rudder was hailed as one of Six Scholars of Caribbean Cultural Studies, thereby underscoring what Brian Meeks, in Narratives of Resistance: Jamaica, Trinidad, The Caribbean, highlights as “the central importance of the popular arts in social analysis.” One wonders when consideration would be given to bestowing similar honors on a few more of our still unsung heroes, such as Shadow, King Short Shirt, Boogsie Sharpe, and Robbie Greenidge.1

Dancing Without Regret: ‘Black Man Feeling To Party!’

“If you can’t prove what you writing, Then don’t write what you writing.“- “Jail”

How have Stalin’s “emancipatory lyrics” channeled our sense of selfhood and independence? What about his hold, not only on the popular imagination but also on the ‘vision thing?’ What accounts for the continued relevance and prescience of The Black Man’s work and its penchant for recapturing sensibilities while refashioning futures?

Listen in as Ian Martin narrates the trajectory of Stalin’s pull: “I came [to the U.S.A.] in 1973…. And when I graduated, I went back to Trinidad and got married [and] was fortunate to see carnival in 1978 and 1979…. When I returned here, I got a comfortable position with one of the largest property casualty insurance companies. Hence, carnival was out of the question for me during the 1980s and 1990s because my busy months are January through March…. However, late one Saturday night in 1991, I turned on the radio and heard Black Stalin’s ‘Ah Feel to Party,’ I immediately said to myself, ‘Stalin is singing about me.’ I felt a personal connection with the song…. It was as if Stalin knew me and studied my situation and was singing directly to me.”

Listen in as Ian Martin narrates the trajectory of Stalin’s pull: “I came [to the U.S.A.] in 1973…. And when I graduated, I went back to Trinidad and got married [and] was fortunate to see carnival in 1978 and 1979…. When I returned here, I got a comfortable position with one of the largest property casualty insurance companies. Hence, carnival was out of the question for me during the 1980s and 1990s because my busy months are January through March…. However, late one Saturday night in 1991, I turned on the radio and heard Black Stalin’s ‘Ah Feel to Party,’ I immediately said to myself, ‘Stalin is singing about me.’ I felt a personal connection with the song…. It was as if Stalin knew me and studied my situation and was singing directly to me.”

Martin interjects the song’s opening lines, ‘Stop all housework you doing/ Tonight we going and have some fun/ Ah just feeling to party/ The way we used to when we was young.‘ Switching back to talk, he continues, “So I spoke with my wife, and the following day we booked tickets to carnival. And that was my first carnival in about 12 years because all my efforts in the 1980s were about seeing about the family and maintaining the job…. Carnival didn’t cross my mind in the 1980s… until that night when I heard ‘Black Man Come out to Party!'”

This classic number resonates and provides a space in which bonds are renewed, thus strengthening the foundation for family and community cohesion, even dancehall. And how have we partied while mindful of our social responsibility to keep family together?

Les Slater, chairman of the Trinidad and Tobago Folks Art Institute (N.Y.), observed: “I know of a few intellectuals who had a problem with ‘Black Man Come out to Party,‘ but I don’t have a problem with it…. Once on Trevor Wilkins Show (WNYE 91.5 FM), we did a program on the best party music that has come down the pike. And, as for my list, I wound up with ‘Black Man Come Out to Party‘ as the best party song ever! That is saying something for an artist whose focus is dealing with the more serious side of life…. He’s saying that after having done all the serious stuff through the years, [husband and wife] have earned the right to go out and party!”

“Ah Feel to Party” has become such a personal anthem that it moves people in many directions, even to reference it in multiple ways. Zennie De Silva, a Trinidadian poet/educator, offered: “Long after the carnival season is over, Stalin’s social/political songs linger on in our minds because we not only listened to the lyrics, but we also danced to them, and as we danced, we sang the words, and they became part of us. For all this, however, his greatest song for me is ‘Tonight the Black Man Feeling To Party.’ When the opening bars of that song start-up, everyone feels to party. It is powerful in its music as well as its lyrics.”

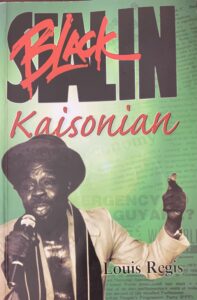

Indeed, “Black Man Feeling to Party” is among a pantheon of songs from Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Bob Marley’s “War,” Ella Andall’s “Black Woman,” and Stalin’s own “Bun Dem,” among others, which elicit instant dancing and singing in unison at the sound of the first bar! Then, as De Silva noted, Stalin never had to instruct his audience to “get something and wave.” Spontaneous waving, dancing, celebration, and even taking a plane to witness and be rejuvenated by a Stalin performance flow naturally from the power of his poignant lyrics and rootedness. His rejection of binary opposites by blending the party feeling with conscious lyrics was dramatized by Louis Regis in his must-read biography, Black Stalin: Kaisonian, noting that Stalin’s early dancing days and time spent playing pan may have shaped his “notion of calypso as dance music… thus escaping the sermon or lecture mode into which other message calypsonians have fallen.”

Regis helped us see more clearly a Stalin who is grounded in and integrates the best of our seemingly contradictory folk traditions by employing what Barry Chevannes, in Between and Betwixt, referred to as “[t]he power of ambiguity and paradox in Anansi.” This, then, is the great strength/paradox of the Black Man: a penchant for getting people to dance and be fun-filled even when confronted by a bleak, stark reality, all the while infusing subversive lyrics that serve as a reality/sound check and counterpoint to the (un)controlled frenzy of the moment.

Regis helped us see more clearly a Stalin who is grounded in and integrates the best of our seemingly contradictory folk traditions by employing what Barry Chevannes, in Between and Betwixt, referred to as “[t]he power of ambiguity and paradox in Anansi.” This, then, is the great strength/paradox of the Black Man: a penchant for getting people to dance and be fun-filled even when confronted by a bleak, stark reality, all the while infusing subversive lyrics that serve as a reality/sound check and counterpoint to the (un)controlled frenzy of the moment.

Indeed David Rudder’s “High Mas” challenged us further to ponder the tension between the sacred and the profane while VS Naipaul, like the calypsonian, realized that laughter cuts both ways. His attempt to battle with misperceptions of his work led him to wonder, in words that come close to shedding light on one of the paradoxes at the heart of “Bun Dem” and other haunting works in social realism: How can one laugh/dance to so much evil?

Hear Naipaul as he expressed it somewhat differently. In commenting on a reading of In A Free State, he wrote, “I had [the audience] rolling in the aisle …though later on, they were a little shocked to discover they were laughing at something people shouldn’t be laughing at. It was too late for them to regret their laughter.” As we know, laughter and dancing often serve as masks in our tradition. It’s a tribute, then, to Stalin’s unapologetic sense of self and unblemished embrace of our struggle, allowing him to have us dance and laugh without regret.

In ‘Bun Dem“, Stalin also settled the score, on the spiritual and humanistic level, concerning how we should relate to those found guilty, in the people’s tribunal, of crimes against good sense and world civilization. Looking squarely into the past in a 1988 T&T Review interview, he said, “In ‘Bun Dem,’ all are stripped of their titles… So I didn’t say queen victoria or queen mary… she became dat woman mary. This was done to express outrage against all perpetrators of injustice against Africans.”

Moreover, by employing eternal flames, he recasts the evil that flowed from the darkness of the colonial mindset. Stalin, like Earl Lovelace, contested the cant that anything bright could have flowed from minds so evil that unleashed such pain. More than that, those “vampires” turned light into darkness only to wallow in the lie of civilizing the ‘dark continent.’ Stalin was uncompromising in his quest to use his acute (in)sight, further brightened by ‘Burning Flames,’ to help us “overstand” the past and, more importantly, brace ourselves to be the future we seek as he compelled us to become subjects of our cognition and masters of our destinies.

This is a mode of resistance that other noble warriors embraced. Once on Charlie Rose’s show (July 2008) commemorating Nelson Mandela’s Long Road to Freedom and his ninetieth birthday, one of the interviewees related an exchange between Queen Elizabeth and Nelson Mandela. According to Rose’s guest, the Queen called Nelson Mandela on his birthday. When the phone was given to him, the queen said, “Happy birthday Nelson,” to which the former South African president and moral conscience of our world responded, “Thank you, Elizabeth.” According to the guest, Mandela’s staff scurried to remind him of the protocol concerning, as the Mighty Duke would say, “putting a title to she name“! Like The Black Man, Mandela was “overs that” long time!

“Stalin both exalts the pan and provides beautiful music for the pan to play… but in the past, people focused more on the message in the music, as opposed to the music in the message.”

The Problem of Voice & Language

“Every Constituency is my constituency.” Black Stalin

What about this man Stalin that allows his voice, message, and music to travel so far into the world and our consciousness? Why has Stalin’s voice and message reached so many worldwide? If Leroy Calliste, our warrior intellectual, forced us to engage the past and the future critically, he also pushed us to extend and appreciate a new range of musical possibilities. How can his singing draw so many into its range despite Keith Smith and Kim Johnson noting, correctly, that his voice is “raspy [and] incapable of great heights or lows, maybe incapable of even scanning an octave.” How, then, could Stalin transform a potential liability into strength?

Underscoring the problem of voice/diction in a stellar performance (at The Trinidad Hilton in the 1980s), the indomitable Lord Relator recreated the traditional tent setting to memorialize our penchant for appreciating calypsonians of various persuasions despite an absence of a “nice” voice and even presentation skills. Relator reminded the audience that “the beauty with Lord Fluke [is that] you hear every word that he is saying but, poor fella, never would sing in time.” And this may even have enhanced his popularity in many areas, even beyond Belmont, where he was the Unofficial Road March King.

Relator contrasts Fluke with “[The Mighty Jackson] who sings in time, but you don’t hear one word that he says.” And striking up a comical pose and making unintelligible sounds, Relator scats, much to the amusement of the enraptured audience. Although both acts may have had what some refer to as “major flaws” by conventional musical standards, yet to calypso and its demanding audiences, that didn’t minimize their popularity. Tellingly, Smith and Johnson concluded in their contemplative piece, “If [Stalin] can hold down a melody, good; his lyrics carry a rhythm that is naturally close to the spoken word as it is heard in the streets,” making Stalin a folk poet par excellence, and, not just for his lyrics.

Related to the problem of voice is understanding the calypsonian’s language. Stalin addressed this issue in (Small Axe, March 2001), “It’s important to see us through our language…. When I say our language, I mean our Resistance English that we use all the time…The… world had to learn what ‘Ire’ means. [Our] music is for the world but, again, through our eyes.” Joan Gordon, a Jamaican cultural activist out of Rochester, N.Y., asserted in a 2008 interview, “Stalin’s music transcends his Trinidadian roots…. progressive people can relate to his music, for it brings positive feelings and profoundly impacts us. Stalin is blessed with deep insight, which you can’t learn in a classroom. [This] contributes to his natural humanity…. Only after Bob Marley wasn’t with us did people appreciate his real genius…. It’s best to appreciate and honor our heroes now when they are with us.” That the calypso may well be giving new life to Jamaican and Caribbean icon Louise Bennet’s vision of “Colonization in Reverse” can be read into the dramatic and increasing interest in the calypso and the steelpan throughout the world.

That the calypso may well be giving new life to Jamaican and Caribbean icon Louise Bennet’s vision of “Colonization in Reverse” can be read into the dramatic and increasing interest in the calypso and the steelpan throughout the world.

Rita Keresztesi2, author of a forthcoming study, “Carnival and Calypso, or the Business of Resistance in the Texts of V. S. Naipaul, Earl Lovelace, and David Rudder”2, says, “As someone from the other side of that bizarrely named…’ Iron Curtain,’ I have always been intrigued by ‘Black Stalin.’ His name captures my Hungarian imagination.”

Indeed, Regis, in Black Stalin: Kaisonian, noted that though Stalin’s name may have held him back in competitions, he always took “unpopular decisions in stride and never [went] public with invective against administrators, judges, and fellow competitors.” Even when a newspaper columnist had the gall to write, as noted in Kaisonian, “Perhaps [Stalin] should consider changing his name. What will the tourists feel on hearing that the Calypso King of this country is none other tha[n] the dreaded figure Stalin?”, the Black Man remained quiet. Little wonder, then, that Black Stalin never viewed such newspaper columnists—”silly reporters”—and other purveyors of gloom and doom as having not even to use Lloyd Best’s term, “mosquito value.”

Exalting the Pan

“[P]an is opening up internationally, and we can’t stop that; we have to come up with new ideas to stay ahead.” Dr. Jit Samaroo

“Steelbands need more respect on carnival day

Steelbands need more respect coming from the D.J.

You have your big box of twenty thousand watts of power

When the steelband pass we cyar hear the bass nor tenor…

So for this festival hear what I want you to do

Turn down your box, look the steelband coming…

We want to hear what the steelband playing.”

Black Stalin, “More Respect,”

Stalin was always ready to celebrate the “hard wuk” that spawns achievements, as he did with “Dr. Jit,” in which he sang:

It was a long hard fight for the panman…

So when word came out that day from U.W.I.

Jit Samaroo would receive a degree

It brought great joy to pan people everywhere.

Here, The Black Man celebrated the famed pan arranger/composer—and nine-time panorama winner with Renegades!—on receiving an honorary degree from U.W.I. in 2003. This aspect of his work and appeal is not lost on the legion of fans, who respect The Black Man, not just for his music but for his enhanced humanity and humility. A disposition fused with an urgency to use the vehicle of the calypso to elevate the status of many of our unsung heroes and other voices from the margins even as he excavated and memorialized pan’s journey, “From playing a pan in Miramar Club to a degree.“

Stalin’s haunting lyrics tug at and serve as our conscience, as he is recognized and appreciated throughout the Caribbean and beyond. It’s interesting to note how many fans and critics instantly retrieve a particular song or catchphrase when looking at Stalin’s transcendental outpouring. St. Lucian Hoagy Stevens reflects: “Even in ‘Hey, Hey, Mr. Panmaker, ‘ we have seen Stalin warning governments to safeguard we art form.” To be sure, Stalin was very conscious of his mission of celebrating and protecting the interests of both the instrument and the player. He explains, “I try to deal with the pan and the man. Like in ‘Mr. Pan Maker‘ where we dealt more with the pan: its development and the need to nurture, safeguard, and refine it; and a song like ‘Pan Gone’ where I deal more with the man.” And he interjected a stanza,

Steelband now in society

But when they say society

Brother, try and understand

That really goes for the pan

They don’t mean the man.

Apart from Kitchener, the Grand Master, few calypsonians have celebrated and defended the pan—our patrimony—as tirelessly as Stalin. This inextricable link between artist and pan prompted Les Slater to observe: “Stalin is always exalting the pan; never seeing it lightly. The fact that Stalin could ask in ‘Mr. Panmaker‘ how many grams of steel to make a pan lets you see the seriousness he attaches to the pan.” Indeed, throughout Stalin’s illustrious career–which may have started in the pan yard–pan has always been dear to him for, as he said, “from small, there was always a tenor pan in the house.” Featuring his early connection to the pan, Regis, in his illuminating biography on Stalin, noted that “Dennis, Stalin’s older brother, of the southern-based Free French Steelband, and in whose care the young Leroy was entrusted, carried him to the pan yard from early” prompting the mature Black Stalin to reflect, poignantly, that “my first crib was a tenor pan”! And it is this deep affinity with the pan flowing with his social concern that is at the heart of The Black Man’s life work and art.

Dawad Phillip, poet/journalist and founder of the San Fernando Jazz Festival, recalls, “Of course, Stalin’s first success in terms of music for pan was, as early as 1967, with ‘Beat My Tune,'” with which, as Stalin recalled, he “went to the [Calypso] finals.” Referring to that period when Sparrow and Kitchener ruled the road, Stalin added, “I got beautiful feedback on ‘Beat My Tune’ as a couple of steelbands played it on the road carnival day… I remember Solo [Harmonites] doing it, and it was on a recording with a steelband coming out of Telco Recording.” Today his musical appeal to the pan is taking off. Stalin reported that “Jah Roots [a steelband] out of Point Fortin seem to take to Black Stalin’s music…. This year they played ‘We Can Make it if We Try,’ ‘Black Man Feel to Party,’ ‘Come With It’…. Roots play a lot of Black Stalin music, and I sang with so many steelbands accompanying me, Skiffle Bunch, Despers, Silver Stars, and Exodus.”

In discussing the appeal of Stalin’s music to the pan, Phillip adds, “It happens sometimes that because of an artist’s lyrical strength people always listened to Stalin as

Emrold “Brother Valentino” Phillip delivers an emotional rendition of his classic Blood Brothers during Black Stalin’s funeral service (January 5, 2023)

opposed to cultivating an appreciation for his melodic contribution and its receptivity by pan…. But now, more and more, the pan community is listening to Stalin’s melody and finding a lot of great tunes to explore on the pan.” Embracing and extending an unexplored notion in pan research, Phillip adds, “Stalin both exalts the pan and provides beautiful music for the pan to play… but in the past, people focused more on the message in the music, as opposed to the music in the message.”

Although “Beat My Tune,” like Shadow’s “The Threat” [1971]—early threats indeed to the then two-man domination of Pan’s Panorama Repertoire—can be viewed as an appeal to the pan, Stalin suggested: “I never went the way of writing a particular song for the pan to play or as some people say a pan song. I don’t see that in the music. I don’t think there is anything one can call a pan song… I view the pan as any other instrument in that it can play any music you give it to, so I never really… concentrate on doing music, especially to attract steelband arrangers.” The discography of pan bears out Stalin’s point, for from European classics and Samba to Jazz and Reggae, pan has made its mark playing all types of music. Stalin breaks out singing his 1994 Classic, “Me ain’t no one tune pan man/ any tune I could play beat me brother, bring on you music sheet/ Whether it’s jazz or classic, name the music I could play it/ I could ramajay, any music I could play…. it’s time you start seeing me as a musician”. And The Black Man rests his case.

Further buttressing The Black Man’s point, Phillip adds, “Sometimes those who make the choices for the steel bands kinda deal with a narrow palette. They look to the usual people. If you look back at the melodies of Stalin’s music, it has all the possibilities for pan… it’s just that somehow he hasn’t been a consistent choice, and it’s not Stalin’s fault…. Steelband arrangers hear what they want to hear…. You can’t tell me that if I’m coming down the road with my band playing ‘Black Man Feeling to Party,’ I cyant mash up de place!” Underscoring this view, Phillip further notes, “At this year’s (2008) Laventille Steelband Festival, the band that stole the show was Renegades… Everybody was playing Kitchener and all kinds of popular and tested songs, but Renegades came through playing Nelson’s ‘All Ah We Is One Family,’ and they mash up the place. What they did was energize a song that arrangers rarely looked at before. And it’s the same thing happening with Stalin’s music…arrangers discovering tunes that they never looked at before.”

Flowing from the increasing pan activities throughout the year, there has been a broadening of the repertoire of the Steelband, especially since many of these events stipulate the genre of music to be played. Phillip reports that at a September 2008 Marabella Pan Festival, part of the arrangement required steelbands to play chutney and a parang. Indeed, these stipulations allow for a broader range of choices, thus allowing bands and arrangers to explore previously unexplored music.

It now appears as if society is finally catching up with Stalin in that, more and more, we are moving beyond our self-imposed limitations as “part-time lovers” of “we culture.” Speaking to this repositioning of the culture of pan in the national psyche, Philip concludes, “Of all the songs Phase Two decided to play at this year’s Laventille Festival was a 1957 Melody tune, ‘Jonah and the Bake,‘ which is an impossible piece of music to play for a band on the move… and you have to imagine how they have to stop and play ‘Jonah…yes pah, you take a bake her, no pah, you tale a bake par.. one gone.’ However, despite the challenge, it was an intricate and beautiful performance” that dramatizes anew that no tune is beyond the range or scope of the creativity that fires the inspiration for each performance. Indeed, Denzyl Botus, the renowned arranger of Despers U.S.A., argues that “We always like to take a challenge, a song [like Rudder’s ‘Monsterrat‘] that everybody figures is hard, and make music out of it” (Everybody’s Nov/Dec 2001). (And, supporting both the ability of panists to play any music and the inherent brilliance of Black Stalin’s music and its compatibility to pan, Kim Johnson, the foremost pan researcher, noted that one of the best pan tunes he has heard was Phase Two Pan Groove performing Black Stalin’s, “More Love”!)

Just as Stalin is committed to exalting the pan, he is equally committed to bearing the burden of documenting pan’s journey, thereby serving as our collective memory bank. Challenging the pan fraternity to tell more of their stories, Stalin implores “Robbie Greenidge, Rudy ‘Two Left’ Smith, Othello Molineaux and other panists to relate their stories in any form; lectures or write about it and let the children read about it” For as he asserts, “Young musicians need to understand that journey… to help them appreciate how panists were able to take their pans from the hills in Laventille or St. James and reach on a stage with Jimmy Buffet and Liberace… Ah, mean, that’s a long trip. If we, panmen, play with these musical legends, they are not just panmen but renowned musicians!”

Fortunately, Stalin’s call for serious documentation of the road traveled by the pan fraternity is being realized. A treasure trove of publications is now developing to introduce, engage and stimulate young musicians around and behind the many bridges of suffering from which the pan rose. Or, as David Rudder puts it so aptly, “Out of a muddy pond, ten thousand flowers bloom.” Both Kim Johnson’s “If Yuh Iron Good You Is King: Pan Pioneers of Trinidad and Tobago” and Myrna Nurse’s “Unheard Voices: The Rise of Steelband and Calypso in the Caribbean and North America” serve as the window through which young panists can be introduced to pan’s glorious and multifaceted history and in the words of those who, according to Stalin, made “the long journey.”

‘University Without Walls’

“I made my debut in the late 1950s…. So I started when we was marching

down to Chaguaramus to tell the Yankees go home.” Black Stalin, July 2008

“Guns shooting there and guns shooting here

and not for hell the government wouldn’t hear.”

Black Stalin, Revolution Time

Little wonder the work of the calypsonians, including Stalin’s, is commanding attention and scrutiny in the public square and on numerous university campuses. Employing the guile and resistance spirit embedded in Calypso’s spirit, Rita Keresztesi, neither tourist nor “Stranger,” writes: “When I proposed a course on Carnival Literature at The University of Oklahoma… I felt the need to justify to my colleagues that it was a creditable subject. Because the name of Mikhail Bakhtin carried the value of being ‘difficult’ and could be identified as ‘theory,’ I put his text on carnival at the top of my reading list that also contained Hollis (Chalkdust) Liverpool’s Rituals of Power & Rebellion and music C.Ds by Black Stalin, the Mighty Sparrow, and David Rudder, among others.”

Keresztesi reports, “The course was accepted, I think, because Bakhtin carried the weight for the artists not immediately recognizable for a reading list at a traditional English department.” This has to be in the best tradition of the calypso, which Gordon Rohlehr, the pre-eminent figure in research on the calypso, refers to as employing “a certain twist of mind” to transcend limitations and (re)fashion futures/possibilities. That the professor is a good student of the calypso is evident in her next activist stance: “Next time I teach the course, I should be able to start my reading list with the likes of Black Stalin a. k. a. Dr. Calliste, Dr. Hollis Liverpool, David Rudder, Earl Lovelace, and the list goes on.”

Keresztesi reports, “The course was accepted, I think, because Bakhtin carried the weight for the artists not immediately recognizable for a reading list at a traditional English department.” This has to be in the best tradition of the calypso, which Gordon Rohlehr, the pre-eminent figure in research on the calypso, refers to as employing “a certain twist of mind” to transcend limitations and (re)fashion futures/possibilities. That the professor is a good student of the calypso is evident in her next activist stance: “Next time I teach the course, I should be able to start my reading list with the likes of Black Stalin a. k. a. Dr. Calliste, Dr. Hollis Liverpool, David Rudder, Earl Lovelace, and the list goes on.”

It now appears that the university is finally going beyond its ivory showers and engaging and appreciating Black Stalin’s intuition and indigenous knowledge. From which fount springs Stalin’s interests and insights? Rawle Gibbons, an educator and playwright, uncovers and reveals the multiple layers of explanation and influences that engulf Stalin, thereby providing clarity and a critical yet creative edge to Stalin’s work: “Some years ago, when I asked Stalin what influenced his perspective, he told me he was schooled in the ‘university without walls.’ By that, he was referring to his classes and sessions as a boy growing up in San Fernando with griots like George Jeremiah, Clemmy George, Roy White, and others. These were all African-conscious, Garveyite, Butlerite individuals. Clemmy George, a griot and chronic collector of newspaper clippings, also wrote an operetta on the 1937 riots’ Winds of Change’. Jeremiah was a primary school teacher whose real passion was African history. His classes learned African songs and dances and, like Bango in Earl Lovelace’s SALT, celebrated Emancipation Day with his own parade since the 1940s. The African influence was also at home, as his mother belonged to the Orisha faith.”

No doubt, Stalin was well-schooled and continues to be appreciative of his informal education. This is evident in his paying homage to the spirit of the times and its impact and continued salience on his social consciousness, even into his mature life. In an interview (T&T Review, October 1988), Stalin explained, “I do a lot of homework. In the late 196os serious work was going on. There was a lot of readings happening in the back of the house—running of books,” capturing, as only he can, the minefields that fired his imagination and ire.

As a public intellectual, Stalin employed the vehicle of the calypso to engender thought and action among pupils and professors alike. This is perhaps best gleaned in Martin Felix’s reflections on his 1980s encounter with The Black Man. Understanding intuitively that, at his best, Stalin is a professor emeritus extending the boundaries of knowledge in the ‘university with walls,’ Felix commented on a Stalin performance: “Stalin, in his trademark centripetal encirclement on stage at Queens Park [Grenada] that night, dressed in all white dashiki with red, green and gold trimming, made me realize that the true intellectuals can be found in the most ordinary packaging [and] that kind of pedagogue is more accessible and more effective because it does not look like teaching.”

Thus Stalin, by valuing and giving voice to his people’s lived realities, understands and employs critical pedagogy much more effectively than our presumed ‘aristocrats of knowledge’ who rely almost exclusively on the fuzzy experts from North American and European universities who are long on jargon and fuzzy modules but short on substance and critical, problem-posing insights and engagements. Is there any mystery why the music of the oppressed—rap, reggae, calypso, and so on—provides us with the most critical element—a bridge—to energize and enliven public education, all the while inciting the youth to chant down Babylon as they refashion futures, ours and theirs?

Felix, a grassroots philosopher himself, adds: “Stalin provided me with a great ‘mini-lesson’ and sent me to do further research as extended class work. The task that Stalin provided me at that concert in Grenada has preoccupied me with an excellent framework for continuing research and a model of best teaching practice… I often revisit Professor Stalin via his recorded ‘mini-/major-lessons’ whenever I need to be reminded of our most pressing but elusive task – ‘Caribbean Unity.'”

If Stalin continuously excavated and revisited vexing issues in our social/cultural history and provided us with new ways of re-interpreting reality, so too has his method been embraced by those who follow and try to understand and promote his vision. Gibbons sees Stalin’s music as coming “out of a love-place: love for the art, the race, his family, the people and culture of Trinidad and Tobago.” Getting to the underbelly of Stalin’s work, Gibbons posits that “Stalin’s music is positive and constructive precisely because he balances artistic integrity and artistic success, offering fair and fearless perspectives.” This warrior spirit flowing from a love for his contemporaries and ancestors is no better place captured than in “More Come.” His calling on the spirit of the slave revolts to compel us to be “iron thorns” in our struggle to expunge the hold that the oppressors still have on too many minds and, more importantly, to become resisters to modern-day vampires and all those who push “unfreedom.”

Black Wizard, another celebrated social commentator and three-time Grenadian Calypso Monarch reflects on the educative role of the calypso and its borderless communities: “I’m a student of Black Stalin, in the sense that I follow his music and learn from him just as I followed the Mighty Sparrow and learned from him…. Stalin has had a tremendous influence on my type of singing… He’s always singing on… political, social, and cultural issues… Although people appear to go for the more party-type music, they still have deep respect for Stalin, who does deep, serious social commentary.” And as if to remind us never to overlook the sometimes hidden registers of the calypso, Wizard reminds us that “Stalin is a deep thinker. Society can’t do without deep thinkers.”

That Stalin is a master of engaging his many audiences in the genuinely public and open university is further gleaned from Jocelyne Guilbault, author of Governing Sound: the Cultural Politics of Trinidad’s Carnival Musics, who notes: “[W]hen I first heard and saw Black Stalin perform, I was struck by the wits and wisdom of his lyrics and his mesmerizing presence on stage. My interviews with other artists, arrangers, musicians, and calypso aficionados further amplified my own reactions to Stalin’s exceptional stature in the calypso scene.” What is it then about Stalin and his work that incites so many at a moment’s notice to honor and experience his work as a vicarious thrill?

That Stalin is a master of engaging his many audiences in the genuinely public and open university is further gleaned from Jocelyne Guilbault, author of Governing Sound: the Cultural Politics of Trinidad’s Carnival Musics, who notes: “[W]hen I first heard and saw Black Stalin perform, I was struck by the wits and wisdom of his lyrics and his mesmerizing presence on stage. My interviews with other artists, arrangers, musicians, and calypso aficionados further amplified my own reactions to Stalin’s exceptional stature in the calypso scene.” What is it then about Stalin and his work that incites so many at a moment’s notice to honor and experience his work as a vicarious thrill?

Though Stalin is known for his great expositions on all aspects of social reality/history, past and present, he must also be viewed not only as a deep thinker but, more importantly, as one of our best conversationalists/listeners and advocates. How else could he, year after year, divine, capture, refashion and express the issues that animate and preoccupy people in their homes and the public square? And it is in this sense that panologist Khalick Hewitt is on point by replaying Kitchener’s timely and prescient comment on The Black Man as captured in “One Hand Don’t Clap”: “Stalin reminds me of a lawyer, pleading with the judge to win a case.” And though he has won the nod of the Calypso judges five times, he is a perennial winner in the court that matters, The People’s Court!

Yet, despite all that has been said, perhaps Wendell Bonnette, an Original Coffee Boy from San Fernando, Stalin’s hometown, may have captured Black Stalin best:

“I am proud to see him achieve this honor. Stalin’s music comes like your children: You can’t love one more than the other… He’s about keeping the culture flowing. Stalin was ‘No Part Time Lover‘ as far as the culture was concerned. He’s all Hard Wuk!”

Click Here for Part I and Here for the Introduction

- Part II is a slightly edited version of An Appreciation of Black Stalin, published in the Trinidad and Tobago Review on October 6, 2008.

___________________

W.R. (troppy) Holder is a founding member of the Caribbean Awareness Committee (N.Y.), co-editor of BigDrumNation, and the author of Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless.

Pantastic article. Black Stalin is our Griot and his stories will last.