|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 11 mins

December 30, 2022 (First published in Trinidad and Tobago Review, October 6, 2008).

AN APPRECIATION

“You cannot see a light if it is put in a place of brightness, so it was necessary that [European colonists] create darkness so that their light would shine.”

Earl Lovelace, Trinidad and Tobago Review, June 1998

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” Proust

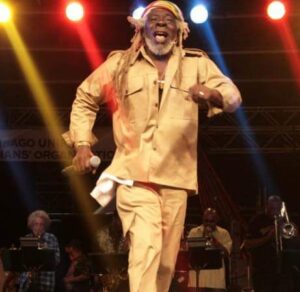

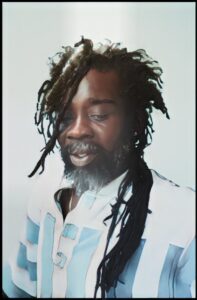

Debate, rather a celebration, broke out on Spiceislandertalkshop.com, an open Grenadian forum on the Internet, when word leaked, from the ivory showers of the University of the West Indies, indicating that at the October 31, 2008 graduation ceremonies on the St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad, The University would be conferring an Honorary Doctor of Letters (DLitt) on Calypsonian Black Stalin. And from this lively borderless yet temporal symposium, I heard that the Academy had finally caught up with The Black Man’s incredible indigenous knowledge and his embrace and celebration of the ritual discourse of the streets. Elation reigned supreme among the masses and beyond. And, soon, people were testifying anew about how The Black Man’s work resonated among so many “sufferers,” in particular, and civilians in general.

“Leroy Calliste [is] one of the truly great exponents of the calypso art,” wrote Bigdrummation on the Internet thread. Attesting his ability to bridge the gap between the sacred and the secular, he continued, “Legions of calypso fans, including the Roman Catholic Bishop of Grenada, revere black Stalin.” Such testimony to the reverential awe that encircles Black Stalin paved the way for an exploration of The Black Man’s life journey, pilgrimage if you will, and a dialogue around his ability, not only to incite contemplation as a precursor to action but also about the force of his work to engender hope and renewal. And in a flash, breaking out in cyberspace, the rum shops, marketplaces, and limes—which may well have spawned the calypso tent–throughout the Caribbean and the world was an electrifying discussion on the enigmatic and iconoclastic Black Stalin, the “Emblematic Figure of Calypso,” and his centrality to our very being and sense of personhood.

RealPolice, another contributor to the thread, thundered, “Most of the pioneer calypsonians in Trinidad and Tobago were either born in Grenada or [had] Grenadian roots. Gypsy … Faye Anne Lyons [and her] father… ‘Super Blue’ [have] ties to Grenada. Therefore, Grenada has lost out culturally to Trinidad and Tobago.” Commie, another contributor, wrote, “I was in Port of Spain when Stalin won the crown with Caribbean Man.” All this, and we haven’t heard from any “Trini or ‘Bago voices to the bone.” yet.

Sometime in late July 1988, I received a call from Dawad Philip, then the editor of The Daily Challenge, New York’s only Black daily, informing me that he had scheduled a five-minute interview for me with Black Stalin to get background information for a short piece for the Friday paper to promote Stalin’s historic performance at the famous, now defunct, Village Gate Jazz club in NYC. But, the Stalin Symposium–rather Dialogues—went on for more than 90 minutes. And, when I sat down to write, I realized that (even now) I had a severe problem: How to truncate Stalin’s words into the few lines that the editor had set aside for the piece. Or, as The Black Man, himself, would, in a later interview, pose the dilemma of kaiso research/writing thus: “How to capture/bottle the spirit of calypso in a few words?” So, picking up the Friday newspaper, I was elated to see a picture of Stalin staring at me from the centerfold between the two pages filled with his words. And when he was presented with the paper Stalin, rather casually, said: “Man, you guys allow me to talk!”

The paradox of someone who has continuously used the vehicle of calypso to advance the cause of the underclass being amazed at his being allowed to talk stunned me. It was then that it dawned on me that my editor experienced the power of Stalin’s words even before hearing them read, for he recognized the error of the Academy’s and media’s penchant for authenticating some voices and de-authenticating others, and this may have been the epiphany that moved him to reorganize the center pages thereby giving voice to, and validating, Stalin’s words beyond his lyrics. Little wonder that, around the same time, the editor started a weekly column, “Word! A Youth Forum,” which brought the marginalized and suppressed, though resilient, youth voices into the mainstream of the media and our popular imagination.

While in the interview, Stalin may not have set out to seek and reshape landscapes, his written words provided him with a new vision. The catchphrase–a core element in his work–“allow me to talk,” helped us see more clearly how the calypsonians’ voice, beyond the lyrics, had been muzzled in the discourse on the calypso. And this may well have compelled us to embrace Stalin’s quest to ‘bend de angle on them’ by unearthing and validating more voices from the so-called margins.

‘Ah, Home-Grown Kinda Thing’

“In times of joy we must be thankful

Because life really have its ups and downs.” Black Stalin, In Times

How did we get to this point? And why have so many been willing to join Stalin on his “ongoing reflective process of self-discovery and self-creation” even as he samples the poetry of everyday people to contest the discourse and dogmas of the (mis)educated elite, downpressors and, to use dub poet Mike Smith’s apt term, ‘intellectual pen dragons,’ hasn’t The Black Man extended roles from being a mouthpiece of the oppressed to that of our ultimate warrior intellectual? How have we been connected to and drawn into his message and method, and what animates his vision/work? Stalin elaborates in a late July 2008 interview:

“It was nice to hear of the UWI recognition. It feels good to know that over the years, I’ve been able to contribute to people’s lives. And that’s all that I set out to do.”

Launching his career in 1959, as a citation to be presented to the Black Man… by the Emancipation Committee of T&T notes, “with ‘Why I Want to be a Calypsonian’… he remained true to what he conceived his profession to be about, a position he states in ‘Wait Dorothy Wait‘:”

“In this world of nuclear and revolution,

The calypso man still singing ’bout rum, and woman

So ah just making sure that when they runnin’ they big mouth,

It ain’t Black Stalin music that they talking ’bout.'”

Though Stalin may never have struggled much to find his voice, walking with him on the road to (re)fashion his distinctive message, he may have encountered one or two bumps. Still, his aversion to smut and degrading lyrics runs deep in Stalin, as he erased less than uplifting lyrics in 1965. As [the late] Keith Smith and Kim Johnson revealed in The Official Calypso Review ’88, after “being encored night after night for a smutty song [that Stalin] was uncomfortable with… he walked out of the [Original Young Brigade] tent mid-season.” Nevertheless, Stalin’s tenacity, faith, and conviction in the ultimate victory of the progressive over the merely crowd-pleasing are at the core of his work and appeal.

Though Stalin may never have struggled much to find his voice, walking with him on the road to (re)fashion his distinctive message, he may have encountered one or two bumps. Still, his aversion to smut and degrading lyrics runs deep in Stalin, as he erased less than uplifting lyrics in 1965. As [the late] Keith Smith and Kim Johnson revealed in The Official Calypso Review ’88, after “being encored night after night for a smutty song [that Stalin] was uncomfortable with… he walked out of the [Original Young Brigade] tent mid-season.” Nevertheless, Stalin’s tenacity, faith, and conviction in the ultimate victory of the progressive over the merely crowd-pleasing are at the core of his work and appeal.

In our July 2008, Symposium, Stalin reflects: “I grow up in a God-fearing home, and I couldn’t go on stage, night after night, and sing smut with my mother still alive…. So the positive vibes were ah home-grown kinda thing.” Here, Stalin demonstrates the exemplary human and noble character of engaging in self-reflection to inspire self and others to greater heights. Stalin adds, “We have to hope that who on smut would make the change one day.” There can be no better testimony of hope, renewal, and transformation than “Wait Dorothy Wait,” which percolated in his mind for a long time before unleashing it in 1985 as an anthem for many.

Getting to the core of The Black Man’s reach, the Emancipation Support Committee citation continued: “The Black Man has placed himself from the outset, within an emancipatory process that has many dimensions and levels. His work is political, cultural, economic, intellectual, and spiritual, but it is always in this emancipatory mode.” It’s a mode of resistance that Stalin embraces and projects, and as he says, “To make a difference. And I’m so happy that over the years, my work has been taken up by people in different quarters and used to make a better life for themselves.”

Few recognize his work’s potential and reach better than Black Stalin, who grounds his career in the people’s life stories and aspirations. He continues, “Because pieces of Black Stalin’s work is people’s anthem, whether it’s like a family would say to each other: ‘We could make it if we try.’ Or, when one is in problems, say, ‘Let’s Look on the Bright Side,’ or draw on ‘Better Days are Coming’ and the ‘The Caribbean Man’ for inspiration and guidance.”

Popular Education Thru Calypso

“Notting, notting… eh strange

In de life of a man out for change.” Black Stalin

How have numerous sectors of our global village been drawing from, and on, his work for inspiration and guidance that’s life-long and life-affirming? Moreover, through the portal of Stalin’s work, many seize the opportunity to use the calypso, in general, and his work to reflect on personal, emotional, and even spiritual growth. For example, commenting on Spiceislandertalkshop.com, Bigdrummation recalls that “Stalin and Valentino headed a ‘Grenadian Posse’ in a 1979 tour of Grenada, Carriacou, and Petite Martinique in the immediate wake of the triumph of the Grenadian Revolution. Posse members included Calypsonian Gypsy- whose roots run deep in Paraclete, and bandleader Roy Cape, whose parents hailed from Grenville.” Thus this new honor for Black Stalin forces people to remember and reflect on the selfless spirit characteristic of the Black Man life’s journey, sowing seeds of possibilities/empowerment in its wake.

Let’s listen in on the reflections of Martin Felix, a Grenadian activist, and educator residing in Brooklyn: “Although short-lived, the PRG/NJM Revolution in Grenada was a memorable and educational experience for me as a youth growing up during that period. It was a moment filled with rich political, cultural, and literary lessons [and] that experience… enriched my life and made me a better person.”

Indeed, Black Stalin reflects on the revolutionaries’ devouring the revolution in “No Way” (1988):

“When they try, and they fail to stop Maurice Bishop,

Yes, they get he own people, Ah say, to Lick him up.“

Although many have made concerted attempts to denigrate and revile that period in Grenadian history, the glories, memories, and possibilities linger in the minds of many. Felix continues, “Much credit for the cultural capital of that era has to be given to the many artists who emphasized the true essence of calypso – popular education…. I witnessed many memorable moments.” Digging deeply into his dangerous memory, Felix reflects on “a Black Stalin performance one very late Saturday night (sometime on or around African Liberation Day in 1980) made an indelible impression. On a solidarity tour, he came to Grenada with Brother Valentino and some of NJAC’s cultural arm performers. Though all the performances of that series

were outstanding, I can recall most vividly recalling Stalin’s performance of ‘Caribbean Unity (The Caribbean Man).’ It was simultaneously theater, spoken word, and a history lesson.” Felix continues, “Probably it was because the song provided some answers and set the parameter for discussing one of the most burning questions I had at the time,” and he breaks out singing:

“You try with a federation/ De whole ting get in confusion

Caricom and then Carifta/ But somehow ah smelling disaster

Mister West Indian politician/ I mean yuh went to big institution

And how come you cyar unite 7 million.”

Indeed, as Felix notes, “Stalin’s Caribbean Unity plea can be said to be the anthem of the moment because he captured the long-standing quest of the unfinished business of a Caribbean nation – a genuine and wider Caribbean Union.” This notion that we, of the Caribbean, are inextricably linked as one is critical in Stalin’s thinking as reflected in the Black Man’s words, “There exists a homeliness and togetherness throughout the Caribbean… away from the politicians [who] don’t know how powerful Caribbean Unity is.” Recent posturing by a few Caribbean governments with talk of a Caribbean Union highlights how far removed these ‘leaders’ and their top-down approach to (mis)governance are from the genuine aspirations of the Caribbean masses whose voices refuse to be silenced. As such, Stalin’s haunting lyrics tugs at and serves as our collective conscience and are recognized and appreciated throughout the Caribbean and beyond. It’s interesting to note how many listeners instantly retrieve a particular song or catchphrase when looking at Stalin’s transcendental outpouring.

Hoagy Stevens, a New Jersey-based community activist from St Lucia, reflects: “Even in ‘Hey, Hey, Mr. Panmaker,’ we have seen Stalin’s warning governments to safeguard we artform… From the ghettos of Soweto to the Laventille Hills, Black Stalin’s music has been used to uplift the downtrodden… I have seen him in performance endless times. I will be there whenever you hear Black Stalin or David Rudder is in town. No matter how small, Stalin always pushes for Caribbeanism and integration. That’s my umbrella, my movement.”

Foregrounding Stalin’s “Caribbean Man” more than 60 years ago, Eric Williams, in The Economic Future of The Caribbean, made the still unacknowledged point,

“[C]hange there must be. And that change, it is equally clear, must be carefully planned and involve a closer union of the separated Caribbean units.” How, then, can present-day leaders talk about a Caribbean Union without careful planning that values the input of the masses? If it’s clear to the Caribbean massive that togetherness arises from the bottom up, why are the ‘leaders’ so deaf to the people’s chants and aspirations? It’s as if today’s leaders never heard or even read, Relator’s “Deaf Panman” with its biting refrain:

Some play B-flat, some play F

They can’t hear a thing because they deaf

But still, come out to jam

And the name of the band is Dr. Williams

Ah hope you understand the masquerade

Panmen with dark shades with hearing aid.

If leaders are now aphonic and incapable of voicing simple truths, then the Black Man’s and calypsos’ role as the perceptual antenna is all the more critical. His music may also be viewed as a lens through which we reflect our self-fashioning, self-transformation, and social awakening as we divine the future in the present. Dr. Jessica Adams-Skinner, now an AIDS Research Scientist and Educator, reflects on her first transformative encounter with Black Stalin:” ‘Caribbean Man‘ is one of my favorite pieces…. I was in high school in Trinidad in 1979 and prided myself on keeping abreast of the political scene in the Caribbean. So when I first heard this song, I was mesmerized by the lyrics and Stalin’s ability to deliver what I was already hailing as a classic in its own right. I could be in a deep sleep, but once that song came on the airwaves, it was as if I was conditioned, almost zombie-like, to wake up and salute one of my heroes. So to sleep through this song for me was total disrespect.”

Indeed, Stalin’s haunting lyrics wake people up while tugging at our collective conscience and pushing us to engage in action, even if merely dancing, as a precursor to social activism. His approach is, as one writer puts it, “more probing than telling, less annalistic than analytic,” to which Stalin adds: “So, I think, not only for me but for writers in general, as Sparalanag says, ‘It’s important that when you write, you try and write sense.’ I welcome the recognition, and I hope that other writers see the importance of trying to contribute to change the lives of people and the world in general.”

Joining the symposium of celebration Ulric Butcher, former T&T national youth soccer player (1974) and one who “dabbles in composing and singing calypso,” adds, “It’s a milestone achievement that enhances Stalin’s other awards…. It also provides motivation and inspiration for younger artists.” Butcher further notes: “It’s not the first time the University has granted such a degree to a calypsonian.” On that historic occasion, Black Stalin was among the first to offer profuse praise to Dr. Slinger Francisco. Celebrating Sparrow and the calypso in T&T Review, October 1988, The Black Man noted, “Kaiso come a long way, and it’s going to go a long way. When I saw Sparrow being honored.” And Stalin interjects Sparrow[‘s] classic line,” ‘Calypsonians really ketch hell for a long time‘… and to see that today universities could watch kaiso and honor it. A kaiso Doctor! Give Praise and Thanks!”

- This, Part I of II, is a slightly edited version of An Appreciation of Black Stalin, published in the Trinidad and Tobago Review, October 6, 2008.

- Click here for Part Two and Here for the Introduction

- #black stalin #stalin #kaiso #calypso #trinidadian culture #caribbean culture

_________________

W.R. (troppy) Holder is a founding member of the Caribbean Awareness Committee (N.Y.), co-editor of BigDrumNation, and the author of Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless.