|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 11 mins

April 15, 2022

An English cricket team was in the West Indies recently to play a 3-Test series. The West Indies prevailed, winning the final Test match in Grenada to the embarrassment of the visitors. This tour went by without significant unpleasantry. But a previous 1953-54 tour by an English team, then called the MCC (Marylebone Cricket Club)1 when on overseas tours, was called ‘the most unpleasant and unfortunate experience in cricket since the visit of DR Jardine’s team to Australia in 1932/33’. EW Swanton would write that ‘as the tour spent its length…incident and misunderstanding followed steadily atop one another until the original fabric of goodwill, despite much good and exciting cricket, had been ripped more or less to ribbons.’

While the Jardine tour has come down to us in history as the ‘Bodyline Tour,’ and many books, articles, and even film documentaries have been devoted to chronicling and analysing events on that particular tour, just three books, however, have been written so far on the 1953-54 MCC tour of the West Indies. The first, by Alex Bannister, cricket correspondent for the Daily Mail at the time, is provocatively titled Cricket Cauldron. The second, by EW Swanton, who wrote for the Daily Telegraph, has the interesting title, West Indian Adventure. Both of these were published in 1954. The third book has only recently been published, in November 2021; it is titled Who Only Cricket Know and authored by David Woodhouse, who has also written on football and horse racing. The three authors are all English. There are also brief accounts in books by diverse hands such as Clyde Walcott, Len Hutton, and Jim Laker.

Quite apart from the controversy that was to envelop that tour, the 1953-54 series is notable for several cricketing footnotes. The first Test, in Jamaica, was the last for the legendary George Headley, brought home by public subscription and selected at the age of 45; the fifth Test, also in Jamaica, was the debut Test of one soon to also become a legend, Garfield Sobers. It was Fred Trueman’s first overseas tour and the beginning of his famous partnership in English colours with Brian Statham. It was the first English cricket team to be captained by a professional cricketer (rare in those days, but one who made a living solely as a cricketer), Len Hutton. It was also the first time an English cricket team travelled by air on a cricket tour to the West Indies (they would return by boat.)

Both teams featured star-studded line-ups, although England felt that they were handicapped by the absence of their star bowler, Alec Bedser. Nevertheless, their number included Peter May, Denis Compton, Tom Graveney, Jim Laker, Godfrey Evans, and Trevor Bailey alongside Hutton, Trueman, and Statham. The West Indian squad featured the three W’s (Weekes, Worrell, Walcott), Jeffrey Stollmeyer, Allan Rae, Gerry Gomez, and the spin twins Ramadhin and Valentine, who had propelled the West Indies to their first-ever Test victory over England three years previously, in 1950. After their embarrassing defeat at home by the West Indies in 1950, Hutton’s team had defeated India in India and regained the Ashes in Australia, while the West Indies had been soundly defeated by Australia in Australia and eked out a test win over New Zealand.

Viewed purely through a cricketing lens, this series of 6-day Test matches was a hard-fought encounter between two strong teams in which the West Indies squandered a two-test lead to succumb in the fourth and fifth games, the third being a high scoring draw played in Trinidad. In the first Test in Jamaica, the West Indies, on the back of good batting performances by Weekes, Stollmeyer, Gomez, and others, and bowling by Ramadhin, Valentine, and Kentish, won by 140 runs. In the second, played in Barbados, a double century by Walcott and a century by JKHolt were the West Indian batting standouts, while Ramadhin had the lion’s share of the English wickets. Resistance from Hutton, Compton, and Graveney could not save England from defeat by 181 runs.

In both games, Stollmeyer was taken to task for not enforcing the follow-on and choosing instead to bat and leave England a sizeable target to chase. In both instances, especially the first, when England were 227 for 2, seemingly threatening to win the game, Stollmeyer had to endure the wrath of the home fans, reportedly needing police protection in Jamaica. In the second, at 214 for 3 chasing 495, the Barbadian crowd was murmuring in discontent. He was vindicated by the result in both, but the subtext of the crowds’ reaction would be impossible to ignore.

‘Cricket had become a rare unifying symbol of West Indian pride and resistance, and passions ran high whenever the colonial masters were involved.’

In the third Test England, led by a Hutton century and incisive bowling from Statham, capitalized on an indifferent batting performance from the West Indies save for Weekes, and resoundingly defeated the West Indians by 9 wickets. A high-scoring draw in Trinidad, with scores of 681-8 declared and 212-4 declared by West Indies, versus 537 and 98 for 2 by England, featured a double century from Weekes, and centuries by Worrell, Walcott, May, and Compton. It set the series up for a dramatic finale in Jamaica. And so it was that the West Indies were shot out by Trevor Bailey in their first innings for 139 and never recovered. Walcott resisted, but Weekes failed in both innings. A double century from Hutton in England’s first innings inspired another English victory by 9 wickets, levelling the series and restoring English pride and a sense of moral ascendancy.

Each of the three books mentioned cover the cricket itself in some detail. Swanton’s book uses his newspaper accounts of cricket proceedings as the body of his text; Bannister’s book is more inclusive and benefits from an intimate association with the MCC team. Woodhouse’s book has the advantage of the long view, written nearly 70 years after the series, and benefitting from not only access to formerly inaccessible MCC records and reports, but from the accounts given by participants either in their own books or via interviews. It enjoys the advantage of a different set as well of social and historical conditions that evolved in the intervening years, allowing a much different perspective from those of the previous volumes.

The Bannister and Swanton books were written and describe a Test series played when England still boasted of an Empire, and when the English-speaking Caribbean islands were still administered as subservient colonies. The dominant view was that West Indians were a promising set of cricketers who, despite trouncing England at home in 1950, still lacked the temperament to be truly competitive. As Bannister, in words eerily prescient of Tony Greig’s ‘grovel’ remark later in 1976, would write, ’I do not think the (West Indian) players as a whole possess that capacity to fightback with unyielding tenacity which is typical of Australians…when he is succeeding, he is wonderful to watch. His fielding can be devastating but is inclined to droop if things go wrong.’

They also needed to be put in their place, a view endorsed by the white expatriates, and white Creoles resident they met. In each territory, Bannister notes, ‘they would be greeted with the inevitable and heartfelt plea of: “You’ve simply got to win. We are counting on you. Don’t let us down whatever you do.”’ Charles Palmer, who managed the 1953-54 team would recollect according to Woodhouse that ‘every day on the tour we were being invited to social functions, invariably with white people,’ who kept telling him that beating the West Indies cricket team was a matter of life or death. Or as English off-spinner Jim Laker would later write, ‘the issue became one of white man versus the coloured man rather than a game of cricket.’ In Wisden’s words, written after the tour by Reg Hayter, Hutton’s team ‘had given the impression that it was not merely playing cricket but was out to establish the prestige of Britain, and, by that, of the local whites.’ Hutton and his team thus came prepared to inflict as sound a licking as possible on these West Indian upstarts and adopted a combative strategy from the outset. There was to be little fraternizing with the enemy; no end-of-day visits to the home team’s dressing room, for example, and social occasions were limited to an absolute minimum. The MCC came armed as well with a traditional not-so-secret weapon, a jingoistic press corps which would make capital of protocol incidents such as a refusal to admit the English captain’s guests into a restricted area. They would have a field day with what they considered poor umpiring and crowd hostility and were afforded a bonanza by the ‘riot’ in British Guiana during the third Test.

Hutton and his team thus came prepared to inflict as sound a licking as possible on these West Indian upstarts and adopted a combative strategy from the outset. There was to be little fraternizing with the enemy; no end-of-day visits to the home team’s dressing room, for example, and social occasions were limited to an absolute minimum. The MCC came armed as well with a traditional not-so-secret weapon, a jingoistic press corps which would make capital of protocol incidents such as a refusal to admit the English captain’s guests into a restricted area. They would have a field day with what they considered poor umpiring and crowd hostility and were afforded a bonanza by the ‘riot’ in British Guiana during the third Test.

Bannister’s Cricket Cauldron, written for an English audience, often betrays the condescending and patronizing attitude of the colonial master secure in the sense of his own superiority and the sense of grievance when matters seemed dire for his team. Journalistic knives were sharpened after the losses in the first two Test matches, when England seemed destined to be humiliated once again, with particular derision aimed at the umpiring. Of the two early writers, he is the one that makes the heaviest weather of perceived umpiring shortcomings in the series; he meticulously records and is repeatedly critical of every decision that seemed to go against England, even in the territorial matches. Summarising what he calls ‘the bones of contention in this unhappy series’, he says that ‘the standard of umpiring was the basic cause of much of the trouble and controversy. Too often it lacked experience, and unfortunately, inexperience is frequently linked with incompetence.’

Hutton himself would publicly express general satisfaction with the standard of umpiring, although he did ask for the rostered umpires for the third Test to be replaced, apparently dissatisfied by their performance in the colony games…or perhaps feared that their premier spin bowler, Tony Lock, had been twice on the tour so far been called for throwing and presented a risk given the chosen umpires. A gentleman by the name of ‘Badge’ Menzies, who was the groundsman at Bourda, was thus drafted in to umpire the third Test! Ironically, the riot at Georgetown appeared to be provoked by Menzies’s adjudication against local heroes Christiani and McWatt.With England winning that Test Match anyway, Bannister would remark in his book that both Menzies and Gillette, the other substitute official, ‘proved very good officials.’

The English players and their ‘cricket correspondents’ lacked Hutton’s forbearance. The players constantly barracked the onfield umpires, criticised decisions, and passed snide remarks when decisions went against them. In one instance an insouciant Fred Trueman provoked an umpire enough to warrant a complaint to the English captain. (Trueman, ironically, was the darling of the West Indian crowds who saw him as a fellow working-class nonconformist but a thorn within his own team. His player bonus would be withheld from him after the tour, and he would not be selected for the tour of Australia that would follow.) There were as well reports of obnoxious behaviour by some of the tourists, which were played up in the local media. Bannister however defended the players: ’The general conduct and behaviour of the MCC party was excellent and the conduct of the overwhelming majority of players exemplary.’

Of the umpiring, Swanton would write that ‘mistakes were made, but they were probably fewer than in several recent series in England’, and of the English players’ behaviour, he wrote ‘One commodity only they were short of, as it seemed to me: a sufficient sense of discipline’, as classic an understatement as one could want. JS Barker, himself English and longtime cricket correspondent for the Trinidad Guardian was prompted to include the following in an open letter to Len Hutton : ’…we submit that the astonishing departures from all canons of good taste and good sportsmanship made by certain members of your team are at once more painful to bear and easier to remedy than any of these charges (laid against the umpiring and crowd hostility)— even if they were all true.’

Swanton’s commentaries do not make capital of perceived slights to or by the English captain or players, nor does he attempt to belittle West Indian spectators and their behaviour. Swanton was, of course, a far more travelled cricket reporter than Bannister, with more experience of Caribbean conditions and vagaries of temperament. Swanton understood intuitively what Woodhouse explores at some length in the most recent book about the tour, that this was a region seething from a history of being exploited and treated like second-class citizens. There were already rumblings of moving to self-governance in the various territories, and an English cricket team that reflected in its composition, attitude and behaviours the prevailing norms within the Mother Country was certain to provoke resentment in certain quarters. Cricket had become a rare unifying symbol of West Indian pride and resistance, and passions ran high whenever the colonial masters were involved.

It is in this context that the bottle-throwing incident at Bourda needed to be examined and in fact all instances of crowd animosity towards the visiting team which bubbled over there after a slow build-up and accelerated thereafter. As Woodhouse also points out, 4 months before the third Test in British Guiana, the British government had placed several nationalist leaders under house arrest and fortified its armed services in the territory. A few months later, the constitution would be suspended, martial law imposed and Cheddi Jagan’s elected government removed from office.

Woodhouse’s book is even more interesting since it raises other dynamics at play within each team. Stollmeyer, for example, was the white captain of a team  comprising the descendants of enslaved and indentured peoples and encountered difficulties in both Jamaica and Barbados when the game appeared to be slipping away due to his decisions as captain. Len Hutton, a professional cricketer, did not belong to the Old Boys’ Club that governed English cricket at the time. The West Indies Cricket Board of Control, as it was then known, and its various member boards, operated more or less as the MCC did in England, creating crises when there was no need. Within the West Indies team, despite presenting a formidable phalanx on paper and in the field, the Weekes/Worrell/Walcott consortium experienced internal troubles of its own. And, of course, the insular inter-island disputes over team selection that persist to this day reared their troublesome heads at the slightest provocation, on and off the field.

comprising the descendants of enslaved and indentured peoples and encountered difficulties in both Jamaica and Barbados when the game appeared to be slipping away due to his decisions as captain. Len Hutton, a professional cricketer, did not belong to the Old Boys’ Club that governed English cricket at the time. The West Indies Cricket Board of Control, as it was then known, and its various member boards, operated more or less as the MCC did in England, creating crises when there was no need. Within the West Indies team, despite presenting a formidable phalanx on paper and in the field, the Weekes/Worrell/Walcott consortium experienced internal troubles of its own. And, of course, the insular inter-island disputes over team selection that persist to this day reared their troublesome heads at the slightest provocation, on and off the field.

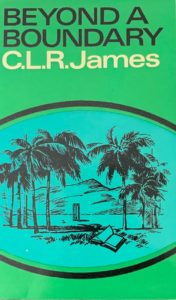

The 1953-54 tour was a watershed event in many ways for both West Indies cricket and West Indian nationalism, events that would unfold decisively over the next decade. It seems appropriate to allow CLR James, who saw it all so clearly, to have the final word: ‘West Indians crowding to Tests bring with them the whole past history and future hopes of the islands. English people, for example, have a conception of themselves breathed from birth…We of the West Indies have none at all, none that we know of. To such people, the three W’s, Ram and Val wrecking English batting help to fill a huge gap in their consciousness and in their needs.’

And here beginneth the lesson for the current aspirants.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Carnival is Over, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Carnival is Over, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

- The Marylebone Cricket Club is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord’s Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John’s Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket and still holds considerable global influence. [↩]

When I was a child my father always tried to get me to play this game, but i didn’t see the appeal. Now that I am older and I have read this, this game has more respect from me.

Fantastic piece by Mr Jaikaransingh. After reading the article I was struck by his grasp of the game’s history and its significance to the people of this fragmented region. Then I glanced at his biography and saw that he is also an academic who has authored regional Caribbean literature text. The UWI, CSEC and West Indies cricket are some of the few institutions we have left. I realize too that Kenneth Jaikaransingh embodies all of this. Thank you BDN for your continued fidelity to the standards, bringing us the best, and bringing out the best in us.

Respect due!