|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 5 mins

February 6, 2022

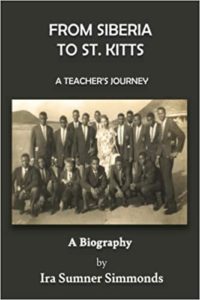

Ira Simmonds’s biography of his high school teacher is the story of an extraordinary teacher-Madame Katzen– told primarily through the personal  correspondence between her and a very close friend and overseas education benefactor. From Siberia to St.Kitts: A Teacher’s Journey draws on over ten years of deep research crisscrossing several continents. The author presents a compelling and captivating narrative of his former teacher, who spent more than twenty years as a “teacher, foreign language supervisor, official government language interpreter of Spanish and French in St Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla.”

correspondence between her and a very close friend and overseas education benefactor. From Siberia to St.Kitts: A Teacher’s Journey draws on over ten years of deep research crisscrossing several continents. The author presents a compelling and captivating narrative of his former teacher, who spent more than twenty years as a “teacher, foreign language supervisor, official government language interpreter of Spanish and French in St Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla.”

Simmonds was so enamored and influenced by the remarkable teacher that he went on to a career as a teacher of French in New York City public schools. After some seventeen years of teaching and reflecting on his path to becoming a teacher, he sought answers and insight into how she may have influenced him and the essence and root of who she was: “Who was [Madame Katzen]… From whence came her indomitable spirit, that all-consuming passion for teaching and learning?” Within five years of her arrival on the small Island of St. Kitts, she had established a “reputation as a teacher extraordinaire and one with well-publicized exacting standards.”

The author’s journey to understand this dedicated teacher has highlighted some essentials about teaching and learning and critical pedagogical tenets of culturally responsive teaching. Early in her career in Shanghai, China, she taught students of Jewish background who fled persecution in Europe before WWII. Simmonds writes that she exhibited “an intuitive quality possessed by great teachers, that the job of a pedagogue entailed more than simply teaching students how to read, write, add, subtract, multiply.” Being an effective and culturally responsive teacher requires the necessary knowledge and skills and, more importantly, the right attitude to one’s students. According to one former student, Isaac Shor-some fifty years after he sat in her class in Shanghai-“she took an interest in the personal lives of her students without invading our privacy and helped whenever and however she possibly could.” Madame Katzen went beyond the traditional role; she cared for the child’s social, emotional, and intellectual development.

During his research, Simmonds was fortunate to receive many letters between Mrs. Katzen and Horace Kadore, a friend, philanthropist, and industrialist. The author notes that “without question (Horace) became the most important person in Mrs. Katzen’s life” as he “provided the resources needed to give her students an incredible foreign language learning experience.” In addition, she used much of this assistance “to feed, clothe and pay school fees and Cambridge exam fees for the neediest among them.” The letters are the narrative thread that binds the book and reveals much of what the author learns about his teacher’s life. They document how she used the funds to establish student scholarships, provide financial assistance to struggling families, and pay travel expenses on class trips to French-speaking islands. For example, one of the author’s classmates, Dany, revealed that once Mrs. Katzen realized that his mother was a struggling single parent, she asked him to have his mother submit a list of her family’s monthly bills. There are many examples of her generosity and dedication to her students.

To be an effective and culturally responsive teacher requires not only the necessary knowledge and skills but, more importantly, the right attitude to one’s students.

On one occasion, she asked permission from the Headmaster to leave school during her morning break so she could visit the hospital to tutor one of her students. He needed help preparing for upcoming exams. There are numerous anecdotes in the letters between her and Mr. Kadore where she talks about students, what is happening to them, and their family situation. She often refers to her students as his “godsons” in correspondence with him. In one of the letters, she says: “your first ‘godson,'” and continues, “You have seen Charles Archibald through the sixth form in the school and through three years in the University of the West Indies. On [receiving] his B.A. thanks entirely to your help…. he was granted a scholarship for further studies.” The bulk of the correspondence between the two spans the forty years she spent in St Kitts from 1961 until she died in 2002. Her letters provided a running commentary on life on the Island and gave a glimpse into her thinking. Here is this fifty-something-plus white teacher, born in Russia and now transplanted to the other side of the world. She writes to him “about her work, the weather, the sugar factory…and its importance to the local economy… her students, hurricanes, poverty, school and island politics, and race relations.”

She mentioned when someone accosted her on the beach in one letter. Shaken up by the incident, she tells Mr. K that “when self-government comes to the island, there will be no safety at all.” He responds to her with sobering words that restore her faith, “I know it is easier said than done, but you have been such a godsend to so many young students that it would be quite wrong for you to condemn all because of one very vile criminal.” These letters between the two remind us of the deep connection and personal relationships built through the lost art of letter writing. What resonated most with the author when he first met his teacher was her revolutionary teaching of a foreign language through a total immersion method instead of the traditional process of rote learning, grammar study, and vocabulary memorization. He described the first day of class as being lost as she addressed students entirely in French. Perplexed, the students wondered if she did not know that this was their first French lesson and that “in the British West Indies, we spoke exclusively two non-Roman languages-English and… ‘Broken English.'” But like the other students, his fear of not understanding her left him, and he listened to her with “new ears.”

As far as biography goes, From Siberia to St. Kitts is a masterful recreation of a life of an extraordinary teacher who profoundly impacted many people’s lives. And like a good biography, it is informative and engaging and shows the intersection between the teacher, students’ lives, and their times. Madame Katzen and her family were at the crossroads of many pivotal historical moments in Western History. First, the Bolshevik Revolution forced them to flee Siberia, her homeland. They first fled to Japan, then to China, where the looming conflict between Japan and China and the impending World War forced them to leave in 1939 for Chile. Finally, after opening a school in Chile and seeing it taken over by local authorities- she is offered a position as a teacher of languages, at the age of fifty, in the small Caribbean Island of St. Kitts.

As far as biography goes, From Siberia to St. Kitts is a masterful recreation of a life of an extraordinary teacher who profoundly impacted many people’s lives. And like a good biography, it is informative and engaging and shows the intersection between the teacher, students’ lives, and their times. Madame Katzen and her family were at the crossroads of many pivotal historical moments in Western History. First, the Bolshevik Revolution forced them to flee Siberia, her homeland. They first fled to Japan, then to China, where the looming conflict between Japan and China and the impending World War forced them to leave in 1939 for Chile. Finally, after opening a school in Chile and seeing it taken over by local authorities- she is offered a position as a teacher of languages, at the age of fifty, in the small Caribbean Island of St. Kitts.

As I read the book, I couldn’t help wondering if we could have learned more about some of her students and how she impacted their lives. What about her relationship with the other teachers? How did the families of students she helped respond or react to her generosity? Though the author has skillfully interwoven the letters into the narrative, they are sometimes repetitive. Notwithstanding these minor reservations, From Siberia to St. Kitts: A Teacher’s Journey is an excellent resource for libraries and teachers and the library shelves of those who “teach” education. In addition, Simmonds’s biography of his high school teacher, who epitomizes what teaching means, contributes significantly to getting beyond the swamp that we see in much education literature today.

Lennel George, a retired NYC High School Principal who teaches at C.W. Post, Long Island, is a Kittitian with a deep interest in Caribbean Literature and has traveled throughout the region, including Cuba.

Lennel George, a retired NYC High School Principal who teaches at C.W. Post, Long Island, is a Kittitian with a deep interest in Caribbean Literature and has traveled throughout the region, including Cuba.

George’s review is simply splendid! Heartwarming and revelatory! Yes! Teaching at its best is a labor of love. A divine dance with curiosity and vulnerability leading to knowledge and hopefully wisdom beyond the classroom!

Reading this reminds me of the sublime joy of living an intentional life, not fully grasping who or how you impact others, but savoring the joy of making a difference, even if only to your reflection in the mirror.