|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 7 mins

January 15, 2022

“Sidney… was truly my brother and partner in trying to make the world a litter better. He certainly made mine a whole lot better.” Harry Belafonte

I very rarely comment on events in the lives of pop stars, Hollywood actors, and other celebrities. They live very different lives from the rest of us. Nevertheless, many of us have a curious fascination with people we shall never meet and whom we see only via television or cinema screen but have come to believe we are their very intimate friends.

I make an exception to write about the late Sir Sidney Poitier, who passed away last week. Probably this is because I grew up alongside and with the films of this remarkable actor and human being and can chart significant events in my own life next to episodes in Poitier’s life and career. To me, his passing has felt like the loss of a distant relative on some foreign shore, one that I had never met but whose life experiences I had come to share vicariously through others.

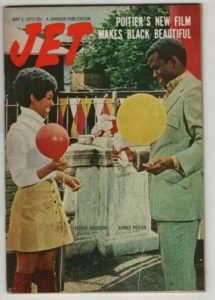

When I was about ten years old, I remember seeing the first Sidney Poitier movie at the Strand Cinema in POS, Trinidad. It was called “Mark of the Hawk,” where he appeared alongside Eartha Kitt. However, that film was not his first significant screen appearance. As early as 1950, he played a young black doctor and suffered horrible racial abuse from an injured criminal played by Richard Widmark (in real life one of Poitier’s good friends, and with whom he would make two other movies) in a tense message film called “No Way Out.” In the 1950s and early 1960s, Poitier would make several of these message films: “The Defiant Ones,” for example, where he was an escaped prisoner shackled to another racist escapee played by Tony Curtis, “Edge of the City,” where he was John Cassavetes’ self-sacrificing buddy, and “A Patch of Blue,” in which he became emotionally involved with a blind white girl. However, in a few film roles of that period, Poitier captured the angst of black people, both in the United States and globally. “Cry the Beloved Country,” made in 1951, saw him as a young idealistic black priest combating racism in South Africa. There were other films like “Something of Value,” where his childhood friendship with the Rock Hudson character appears to evaporate in the turmoil of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya.

In these films, however, the rebellious Poitier character would either come to an unfortunate end or redeem himself in society’s eyes by saving Glenn Ford from hoodlums in Blackboard Jungle or Clark Gable from a Union prison in “Band of Angels.” In “Mark of the Hawk,” he was an African activist seeking racial equality via peaceful means. In 1961 he would reprise on film the critical role of Walter Younger, which he had played on Broadway in Lorraine Hansberry’s celebrated drama, “A Raisin in The Sun.”

For 1950s audiences in the Caribbean, seeing Poitier onscreen in significant roles was a revelation. His was no longer Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen of “Gone with The Wind,” Stepin’ Fetchit of so many stereotyped portrayals of the black buffoon, or the walk-on appearances black singing and dancing groups in the odd MGM or RKO musical.

Even if Poitier and we, in the Caribbean, still operated within the constructs of white European and American value systems, here was a young Black male with substantial presence, providing an onscreen companion piece to the exploits of a winning West Indian cricket team in England. Or the triumphs of Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, and other Black boxing legends, the new frontiers in football led by Pele and the Brazilian football team, and the socio-political currents of regional nationalist movements that would lead ultimately to independence for most of the English-speaking West Indian islands by the end of the 1960s.

Sidney Poitier served as Bahamian Ambassador to Japan from 1997-2012. In his honor, Paradise Island Bridge was officially renamed “The Sidney Poitier Bridge.”

In a handful of his films, the color of the Poitier character seemed secondary to the humanity of the part he played. Such a film was “The Slender Thread,” one in which he was a volunteer handling a Help Line for would-be suicides; he becomes the fragile lifeline for an intended suicide (Anne Bancroft) whom he never actually meets. But this movie and others like it would appear after his lead role as the itinerant but multi-skilled Homer Smith, who helps a group of refugee German-speaking nuns build a chapel in the Arizona desert. “Lilies of the Field,” made on a shoestring budget in 1963, remains one of American cinema’s most endearing and uplifting landmarks. In addition, Sidney Poitier would become the first black American male to win an Academy Award Best Actor.

Poitier’s… legacy will not easily be replicated or forgotten by fans and the waves of black actors who have followed in his footsteps.

By the mid-1960s, however, Poitier, who had marched with Martin Luther King in the Civil Rights Campaign, had fallen out of favor with the growing militant mood of Black America encapsulated by Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X, H Rap Brown, and the Black Panther Party. In their eyes, Poitier was playing versions of the black experience sanitized for white audiences, none so prominent as the black super-hero doctor planning to marry a white girl in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” The Poitier screen image was too bland and asexual, and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” was the last sugar-coated pill they proclaimed themselves able to swallow. In the Caribbean, too, Poitier’s stocks diminished; black audiences turned to Fred Williamson, Jim Brown, and Pam Grier, kicking back forcefully at the dominant white culture that repressed them.

Ironically, however, in 1967, the same year of GWCTD, he would play two more iconic roles, in both of which the fact that his character was black was central to the story. The first was “To Sir With Love,” playing a black teacher from the Caribbean confronted by a troubled multi-ethnic group of East London teenagers. The second was “In the Heat of the Night.” His black detective Virgil Tibbs slaps a powerful white landowner after being reluctantly co-opted into investigating a murder by the redneck sheriff of the Southern town Sparta. It was a scene that created considerable controversy in the racist enclaves of the United States at the time. Even the Black butler in the film serving lemonade is horrified.

For a while, smarting from the remarks of his Black critics, Poitier made films that were purely commercial in intent. Sequels like “In the Heat of the Night” featuring the Tibbs character, the western “Duel in Diablo,” the escapist adventure “The Long Ships,” and the anti-Cold War statement, “The Bedford Incident.” But from 1970 onwards, Poitier turned to directing and acting, making movies that quietly but significantly recognized the black presence and black audiences in the USA. Finally, Poitier turned to comedy when romantic fare like “For Love of Ivy” and “A Warm December,” featuring Jamaican actress Esther Anderson*, did not fare well as his other films at the box office.

Pointer made several with personal friends like Harry Belafonte, Bill Cosby, and other leading black talents. Movie-goers of all hues responded positively to “Buck and the Preacher,” “Uptown Saturday Night,” and “Let’s Do It Again.” One of them, “Stir Crazy,” which he only directed, was in 1980 the highest-grossing film made by a black director up to that time.

These comedies would play to sell-out crowds at the Empire Cinema on Frederick Street, POS, Trinidad when they appeared locally. On local television, comedies in a similar vein like “Love Thy Neighbour,” a series that lampooned race relations in the UK, and featured Trinidad and Tobago’s Rudolph Walker among the leads, had begun to appear and were immensely popular. In addition, this was the era in which situation comedies featuring black characters also began appearing on American television: “Sanford and Son,” “Good Times,” “The Jeffersons,” all played at prime time on US networks and locally.

Poitier returned briefly to more serious entertainment films in the late 1980s, playing key supporting roles in a remake of “The Day of the Jackal,” an FBI agent in “Shoot to Kill” and as part of an ensemble cast in the heist film “Sneakers.” He appeared more and more in television films and series: “Separate But Equal,” which focused on the role of Thurgood Marshall in a landmark Civil Rights ruling argued before the US Supreme Court, and as Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and de Klerk” in 1997. But his film and television work would give way to retirement, family life, and other interests. He would write two autobiographies, the second of which, The Measure of a Man, would not be just a spiritual autobiography of sorts. It would become an international bestseller. He served as an Ambassador for the Bahamas to Japan and UNESCO.

Sidney Poitier would win many honors in his lifetime: a knighthood from the Queen of England, the US Presidential Medal of Freedom. However, he would live a private personal life as well, not without its difficulties, but lacking the noise and publicity on display in the lives of so many other celebrities. From all accounts, he was in his demeanor as humble, self-effacing, charming, and gracious as so many of the characters he played onscreen.

And it is through the screen performances, he became so significant a part of the lives of those West Indian movie-goers who came of age during the ’60s and ’70s, and for which we will best remember him.

His legacy will not easily be replicated or forgotten by fans and the waves of black actors who have followed in his footsteps. Denzel Washington, receiving his own Best Actor award in 2002, spoke on behalf of many of his generation: “I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps. There’s nothing I would rather do, Sir.”

Rest in peace, Sir Sidney. Walk, in grace, amidst the lilies of the field.

*In a recent conversation with BDN, Ester Anderson suggested that a combination of racism and a conservative backlash to the then prevailing Civil Rights/Black Power moment likely gave Hollywood an excuse to not sufficiently push ‘A Warm December’ as much as was required. And this contributed to the initially lukewarm reception of the film.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His collection of short stories, The Carnival is Over, is being issued to a broader public in February 2022. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

« The Lillie’s of the field » my high school reading assignment.

How heavy and noble to represent a climate, a Nation and support a movement as it were, is and unfortunately always will be. The burden to act in a manner that pleases the general population which is clearly divided on all subject matter relative to self and humanity. I cannot imagine this incredible man serving God and Country with every ounce of his being. May God have a special place for him to lay his head to finally rest in peace.

Thank you so much for reminding us of SP’s talent, charm and power. Although a great actor, with ample evidence in the films you mention, it is perhaps, as you intimate, that he didn’t have to try too hard for some roles!