|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 10 mins

May 25, 2020

“Mussolini you too brass face and bold/ Ah mean to claim our land that’s filled with gold…. We are going to fight until we get you in the grave.” “Advantage Mussolini”, – Roaring Lion, (1936)

“The national flag is a lovely scene/ With beautiful colors red, gold and green/And a black star in the center/ Representing the freedom of Africa.” – “The Birth of Ghana,” Lord Kitchner (1957)

“The race question is subsidiary to the class question in politics, and to think of imperialism in terms of race is disastrous. But to neglect the racial factor as merely incidental is an error less grave than to make it fundamental.” C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins

From its inception, the calypso, which the Mighty Duke (1932-2009) characterized as “an editorial in song of the life we undergo” (“What is Calypso?”), has been concerned with all facets of society and life, mainly focusing on Africa and its Liberation. There’s no better representation of this than Roaring Lion’s decisive repudiation of Mussolini’s attack on Ethiopia and the embrace of Haile Selassie, as reflected in the opening quote. Lord Kitchener, too, some twenty years later, in welcoming Ghana’s independence in “Birth of Ghana,” celebrated Dr. Kwame Nkrumah as one who “endeavored continually/To bring us freedom and liberty,” thus setting the stage for the independence movement in Africa and the Diaspora. Such reclamation of, and identification with our African past, underscores calypso’s Return to the Source.

Within this milieu, the Mighty Duke entered the University of Calypso to discover and distill his unique and uplifting message of Freedom for Africa and beyond. There can be no doubt that African Liberation was the animating vision and a central tenet of his work. From “Afro-Chant” (1964) thru “Black is Beautiful” (1969) to the defiant “Uhuru” (1977) and “How Many More Must Die” (1986), to the haunting “Man Child of a Slave” (1980), Duke was an uncompromising advocate in his stance that Africa must be free as he asserts in “Freedom in Africa” (1980), “dialogue is over…it is war” to topple the oppressors. From early, he was a relentless critic of the vile apartheid regime.

If, as The Mighty Duke suggested that “calypso is more than a work of art,” then on his life-long pilgrimage to re-educate himself—and us all–while contesting the stranglehold of the traditional centers of learning, he was much more than an artiste and calypsonian. For, by challenging the euro-centric basis/base of colonial and neocolonial society, Duke’s calypsos created a pathway toward our self-knowledge and self-fashioning as actors in charge of our futures. And in this sense, he championed African Liberation Day’s ideals, and Pan-Africanism, even without having voiced those terms in his lyrics. There was no need; his work is suffused with a call for African dignity, resistance to downpression, and true emancipation.

Duke was an organic intellectual who developed his intelligence and knowledge from keen observation and critical engagement with his environment. Liming in and beyond the kaiso tent was Duke’s true laboratory and classroom as he imbibed not only the poetry of everyday life but also the native wit and intelligence of the kaiso titans with whose works he grounded. For Duke, then, the kaisonians’ stance before him reflected in such warriors as The Growling Tiger, about whom Rawle Gibbons writes in “No Surrender,” “appeal[ed] to the conscience of the world” in song resonates, even today, “The gold, the gold/The gold, the gold/ The gold in Africa/ Mussolini want from the Emperor,” and The Roaring Lion’s call for an uprising, which frames this article, provided a foundation for Duke’s development–and ours.

Duke’s interventions into the calypso discourse were in the tradition of the great African griots, encapsulating the memory of man while serving both as a clearinghouse and storehouse of our indigenous knowledge—which is distilled beyond the walls of the more formalized centers of miseducation. Indeed, underscoring the strong progressive currents in his work, he affirmed, in a 2007 TriniSoca.com interview, “I grew up in that era of resistance,” recalling the Tubal Uriah Butler-led workers’ uprising in Trinidad and Tobago of the 1930s, which set the stage for independence, both personal and (inter)national.

‘Kelvin Pope’s… real legacy may well be that he continually chipped away at the foundation of lies–upon which racial superiority and Africa’s darkness were constructed–by constantly attacking euro-centrism, apartheid, and un-freedom.’

Kevin Pope was one of that rare breed of calypsonians who excelled in all spheres of the calypso, having an uncanny ear for zeroing in on the street vendor’s patter while capturing, recasting, and retelling the drama and nuances of the best lime or spontaneous social gathering. Indeed, many of his comical songs and double entendres can be heard/read as if one were listening in on a grand lime. From ‘Social Bacchanal’ and ‘One Foot Visina’ to ‘Freaking Streaking’ and ‘Horn Proof,’ Duke employed a minimalist approach which facilitated his storytelling in a manner that allowed his varied audiences to experience his craft much more vividly than if the drama of his songs were re-represented on screen by the best filmmaker. He was a boss lyricist who, by the sheer power of his crisp and deft word choice and masterly rhyme scheme, brought his audiences into his scenes and compositions as participants/observers. Duke didn’t sing to an audience but with them. The bard served as a vehicle that gave voice to those on the margins. By recording the lives of ordinary folks in song, he not only valued the wretched of the earth but may well have re-fashioned and extended our lives.

Drawing from the well of our subjugated knowledge and suppressed memories, and bolstered by his own research, he refused to believe what the society said and felt about the poor and downtrodden and, instead, went beyond authorized history to develop a counter-narrative to contest the dogmas and lies, about Africa and Africans at home and abroad. Accordingly, in a 2007 interview, he asserts, “My Black consciousness was awakened as a little boy… Once I am doing a serious song… I do a lot of research. I would go to the library and spend weeks looking for information.”

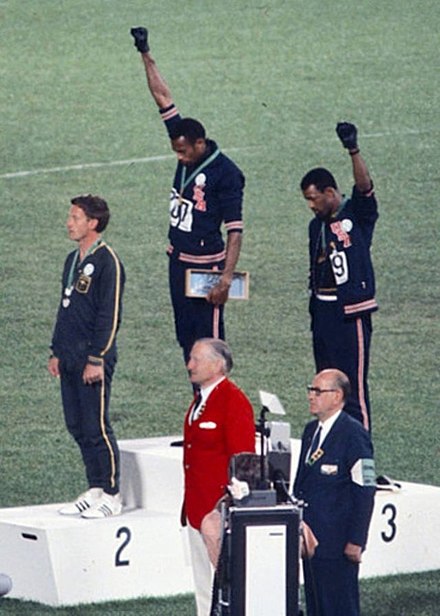

Indeed, in 1969, a mere five years into his recoding carrier and, as Louis Regis suggests in The Political Calypso: True Opposition in Trinidad and Tobago Duke, being a student of magnetic world events such as the Black Power Movement in the USA and the affirmation of Black pride by Tommy Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, in reflecting the New African Spirit, penned the evergreen, “Black Is Beautiful”:

A many, many, many years it took

Now we have found the natural look.

A many, many, years it too took.

For us to find the natural look

Suddenly out of the blue

This thing has struck like something new.

Everybody young and old/ Going Afro telling the world

Black is beautiful/ Look at the gloss.

Black is beautiful/ It’s the texture, of course

Lift your head like me/ You gotta wear the color with dignity

How it go/, Black is beautiful.

Ah, sing it out loud.

Black is beautiful/ Say I’m Black and proud.

It’s high time that we/ Get rid of this slave mentality…

Proudly I say without pretext/ No more inferiority complex…

Because we know…/ There is no in-between in race…

The timelessness and prescience of this song, “announc[ing] the aesthetic revolution which accompanied the revolution in consciousness,” cannot be understated. Reflecting on this watershed song today, a colleague asserted: “I recall growing up literally and figuratively to Duke’sBlack is Beautiful’, etc. To me, that was the first soundtrack of [my] black consciousness journey.” Indeed, Duke’s sentiment has resonated through time, taking on new life in Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” (1980) and its popularization of Marcus Garvey’s divination, “emancipate yourself from mental slavery.”

Chipping Away at the ‘Foundation’ of Lies

“[T]he poet appropriates the voice of the people and the full burden of their memory.” Wole Soyinka

“Until liberty, all Blacks possess/ Your Kwame cannot rest…

Do you know what Nkrumah said/ ‘We don’t want the crumbs/ We want the whole bread.'”

Chalkdust, “Theme For African Liberation Day,” 1976/1977

“When they want to destroy a people/ The people’s culture they first destroy,” Mighty Duke, 1995

Duke’s music traveled to all corners of the world where Africans lived and yearned for social justice, dignity, and, as Fanon implored, “restoration of nationhood to the people.” Duke was part of a cadre of cultural warriors–in reggae, rap, calypso, Afro-Beat, etc.–whose work helped to explode the myths of Africa’s past while upending the badge of servitude.

How ironic is it, then, that he assumed the performer’s name, The Mighty Duke? While he performed and informed with the nobility appropriate to his title, it is now, in his physical absence, that his divine inspiration and intervention into calypso’s sphere of existence and our common consciousness that both of his names take on added significance.

His real legacy may well be that he continually chipped away at the foundation of lies–upon which racial superiority and Africa’s darkness were constructed–by constantly attacking euro-centrism, apartheid, and un-freedom. It is in this sense that Kevin Pope, anticipating Chinua Achebe, contested “the colonization of one people’s story by another” while embracing Chalkie, another champion of teaching “The Right History,” challenging us to “write that down in history.”

Duke’s contestation of the then-dominant paradigm only fully entered my view in 1988 while trying to engage a group of fourteen and fifteen-year-old Brooklyn inner-city students in the few days of African History required by the NY City Department of Education. It was students’ continued rejection of the drab, sanitized, and disempowering authorized text which led me to share Duke’s seminal “Teach the Children,” a song that challenged the continued glorification of Europe and its denigration of all things African.

In the song Duke offered:

Now from the moment I came of age, I clearly remember.

They used to have me marching across a stage, singing Rule Britannia.

But of my ancestry, listen what they taught me/ Tarzan ruled the jungles of Africa.

That’s why I beg you/ Teach the children.

The Truth which they hide/ So, their forefathers they see with honor, respect, and pride.

Teach them that Africa is where civilization began/ Teach them that Africa was the cradle of creation

Teach them, Africans were the first men to walk on this universe/ Ancient Egyptians were all Africans…

Teach them; the Holy Koran says Moses was an African/ Oh, how they glorified Europe’s past in the books that they gave me.

But they show my people as barbarous, no culture, no history/ All Africans were savage,

We had no heritage/ Until they came and preached Christianity.

But that’s why I beg you/ Teach the children, teach.

The truth they must learn/ How the vulture stole our culture and called it their own

Let them know that Africa is the land of King Solomon/ Who married Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, an African.

Teach them, Plato and Socrates taught African Philosophy.

Teach them, Poetry, music, and art were Africa’s own from the start.

The year’s calendar was first practiced in Africa.

Bilal Islam came from Kush; he was African

They never told me once in Africa; we had great empires.

Like those of Axum, Songhai, Mali, Ghana so many others

Like Monomotapa and Mesopotamia were great cities built by my ancestors.

That’s why I beg you/ Teach the children.

You got to show them from books of their past…

Like the Vanquished Cities, the Great Maccabees and

Tell them that in Africa, as great historians know,/ Man found his utopia nearly four million years ago.

Teach them/ The Akkadian was the first language used by man.

The Demotic Scroll was the first writings in this world.

Medicine began by Imhotep, who was Egyptian.

Teach them… / Pharaohs were Kushites who were blacks, not whites.

After the class listened to the song, all hell broke loose while reading it as poetry. Instantly warming to Duke’s message and his manner of presentation, one student, thundered, “Yes! Teach the Children that we’ve been taught lies!” This song’s energy sparked a desire to explore the hidden curriculum in popular culture. It pushed us to more fully engage knowledge sources embedded in reggae, rap, calypso, and writers whose works were banished from the curriculum. Against this drumbeat, I shared excerpts of George James’ influential “Stolen Legacy,” which led the classroom community to make connections between James’ book and ‘Teach the Children‘ while critiquing the classroom text dismissing it to the dustbin of history.

In 2007, TriniSoca.com Interview, Duke, our warrior intellectual, reflected on his early education thus: “As a child, I didn’t know much about Africa except… the Tarzan story and that sort of thing… I was taught nothing about Africa except… people were born slaves, and they came from Africa.” It was this miseducation prevalent then, and perhaps today, and the imposition and privileging of the slave master’s story which led him to challenge the euro-centric distortions and lies and write the song “after [he] got the knowledge and understanding” to reveal and center discourse on the hidden truths of Africa.

Perhaps we may best appreciate the measure of this giant of a man if we embrace his method of constantly chipping away at the foundation upon which the colonialists constructed society to benefit themselves. Grappling with the race/class question as framed by CLR James, Duke employed the calypso as a weapon to undress neocolonialism as in “Whose Land is This?” in which he sang truth to power:

…After independence, well everyone was glad/ In our ignorance we say it is progress for Trinidad

But the same old colonial system remain as you see/ They just put a few black faces where whites used to be

You tell me this land is mine/ You think I am an asinine

The whole thing is a pantomime to keep me sublime/ The poorer class still oppressed.

The elite class at the best/ That is what I call treachery by the neo-colonials of this country…

They join hands with the powers that be/ To exploit the poor people of this country…

The wealth of this country should be shared by all/ Not just the small minority hanging around Whitehall.

Here again, while his country is the point of departure, he spoke to his brethren throughout Africa and the Diaspora, where neocolonialism thrives.

Though the Mighty Duke transitioned in 2009, the body of his work, like that of the great bards before him such as Growling Tiger, Atilla the Hun, Kitch, resonates through time. Indeed, his passing casts a new light on the African proverb, “The dead only die when the living forgets them.” The Mighty Duke lives! He lives not only in our memories but through his lyrics. His transformative work continues to guide us on the Freedom March. Indeed, in “Black Is Back he reminds us that it’s “forward we are marching”!

////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\

W. R. (troppy) Holder, an emancipated NYC public educator and a founding member of the Caribbean Awareness Committee(NY), is the author of Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless (Peter Lang).

#AfricanLiberationDay #AfricanLiberationDay #AfricaDay #PanAfricanism #PanAfrican #ALD #Calypso #BlackPower #BlackExcellence #BlackLove #BlackHistory

This was certainly a well-researched and absolutely magnificently written piece. Good read. The information is timely with respect to the current situation today (G.F). We need to empty our half-full glasses and start from the beginning. History is important for the impressionable minds now.👌✌🤝

Man, you write like Coltrane! Hills and valleys. Shouts and whispers. All within a tightly knit, down low, scholarly underpinning.