|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 18 mins

Excerpts from Classroom Calypso: Giving Voice to the Voiceless, (Peter Lang Publishing, NY 2007), a compilation of fourteen to eighteen-year-old Brooklyn high school students writings about, and challenging, rampant injustices such as police misconduct between 1989 and 2000. This chapter speaks to the ‘Uprising’ that’s refashioning American society’s fabric.

“Could not recognize the faces standing over me/ They were all dressed in uniforms of brutality.” – Bob Marley, “Burnin’ and Lootin’.”

“[P]oor America is maintained by the police. Its denizens are familiar with nightsticks, handcuffs, and jail cells.” – Walter Mosley, What Next: A Memoir Toward World Peace.

“‘Are Drugs, Gold Chains, the New Air Nikes and Mo’ Money the elements of crime? Or, are the Guns, the Badges, and the Nightstick’ – all under a Blue Uniform – ‘the elements of crime?’ All over the land it appears as if ‘our’ officers of the law take advantage of the fact that they have badges, guns and nightsticks. These officers appear to enjoy beating down anyone of African-American appearance for the fun of it.” (Crossing Swords, 1991)

I well remember the day a student approached me during her lunch period and said, “Yesterday, while walking with my mother, I saw a poster that I knew you would like.”

“Really?”

“I thought about tearing it down to show it to you but didn’t.” And, after a slight pause, she continued, “It said, ‘Are Drugs, Gold Chains… the elements of a crime?’”

“That’s very interesting and…”

Handing me a few handwritten sheets of paper, she said, “I wrote an essay about it… I hope you like it.” Chsauna Jenkins’ essay, begun above, continues…

Yet when our community complains and rises up, some whites are quick to say that black people cling to the “victim- focused identity”(1) claiming that we are blameless for crimes we are accused of and blaming our troubles on the ‘unfair justice system.’ Actually, it is the ‘white man’ himself who is clinging to this myth and not quite opening his eyes to take a look at the unfair treatment, and the outlook of some whites to blacks in all types of situations, whether it is a judge to a suspect or citizen to citizen. As such, society clings to a system that victimizes blacks.

And twelve years later, on January 20, 2003, the New York Times, as if extending/updating Chsauna’s view, editorialized, “If many black Americans are living a version of King’s dream, they live it with the perpetual consciousness that the dream still has sharp boundaries, places, and situations where it does not yet apply. And, as Trent Lott has notably demonstrated, some white Americans still cling to a version of history that denies even the fundamental premise of King’s greatest hope for his people.” Despite the progress made, the dream is still as elusive today as in 1990. So, by speaking out against those who cling to and act upon the worst aspects of the dream deferred’, Chsauna Jenkins, in her incendiary essay, challenges readers to think about creative ways of expunging the stigma of race and the badge of servitude.

Indeed, a key aspect of the classroom was to cross borders; move from the oftentimes restrictive curriculum to a consideration of life’s curriculum. After all, as Brooks and Brooks note, “[w]hen magnetic events occur that exert an irresistible pull on students’ minds, continuing with pre-planned lessons is often fruitless.” In short, once Chsauna resisted the urge to pull down the poster by instead using it as a vehicle to express her thoughts on race in America, I couldn’t resist sharing her essay in the classroom. However, her interest was not part of the general curriculum. The student’s interest drove ‘instruction’ in a different direction. The essay continues…

“There are several instances of blacks being victimized by white officers of the ‘law’ and the cops getting off scot free. A police officer’s job is to enforce and maintain the law, not to brutalize whoever they want and then hide behind a badge. But this brutalization followed by cover-ups seems to be what the cops do and what the system sanctions.“

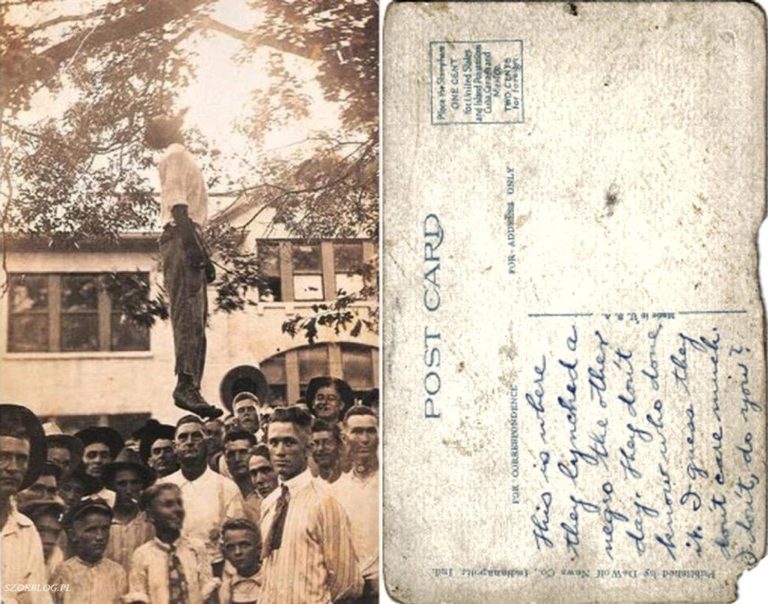

Could it be that Chsauna’s words above were a warm-up to a discussion of the ugly legacy of legal lynching’ as celebrated by many whites in the early twentieth century, who, for some time, used the U. S. postal services to send cards? One read, “This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it, your sone (sic) Joe.” (NY Times 1/13/00) Or, was the subject of her essay a prefiguration of the forty-one bullets that police would fire at a single unarmed Bronx resident who was ‘chilling’ in the vestibule of his apartment building?

Insert from Chapter 16: Classroom Calypso, p. 221.

“Southern trees bear strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood on the roots, Black boy swinging in the southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar tree.” Abel Meeropol (1937)

Go Away!

Sonia Springer (16 years)

It’s a shame how they treat the dead/ You see them

Hanging from a tree by their head/ They put these horrible pictures.

On a post-card, And they don’t care./ To them, it wasn’t hard.

People stand around like it’s a show/ And go out of their way.

To see a black man die tragically/ This is nothing new to them.

And nobody gives a damn ‘bout the victim/ Sometimes they line up in an orderly fashion.

And watch an innocent man die/ For their satisfaction.

The lynching of a 16-year-old on a postcard/ These people should be behind bars.

This hatred is still with us today/ And I pray someday it will go away.

Could it be a segue into a discussion of the treatment meted out to three [Freedom Summer Activists] whose only crime was to challenge the segregated south when Senator Strum Thurmond reigned supreme? Would the ‘glare’ of the bigotry, which Chsauna and so many of her contemporaries write about, ever be ‘unsoftened by age’ or reason? Let’s continue with Chsauna’s essay that she provocatively titled “Uniformed Hoodlums in Blue”:

“Rodney King just experienced such an ordeal in California. Although he wasn’t even resisting ‘arrest,’ the cops beat him senseless. If someone hadn’t taped the incident, the cops would have gone on as usual, and King would have been just another statistic. How many beatings have cops belted out that no one taped? How many Rodney Kings are there out there?

A similar incident happened in Teaneck (New Jersey) about a year ago. Phillip Pernell, an African-American youth, was shot by a white cop. The cop said it was self-defense and justifiable use of force. How could this action be justified if the youth had his back to the cop?

Everybody who lives in the United States should know that racism and prejudice exist among us. All of us- blacks and whites- have certain basic rights, which flow from the same constitution, and we share the same protectors- the police.

However, unfortunately, most government officials, particularly law enforcers, are of different races and backgrounds than the increasing minority population, and sometimes many public officials allow their own personal biases to prejudice their actions. This is what comes out when white cops see a group of black teens (males), especially in a ‘nice’ car or just standing outside in their neighborhoods.

Some cops want to nail us any way they can. And, hiding behind their uniforms and badges is the safest way to victimize blacks. The cops can always say, “He was speeding,” or “He was resisting arrest’” or “I thought the nig… had a gun.” Any lie the police tell is often accepted as truth. What should we do now?” (Crossing Swords, 1991, pp. 116-117).

“Perhaps it will… seem astonishing someday that African-Americans continue to suffer discrimination because of the historical consequences of their skin color, all the systemic effects that arise from having been enslaved and then only partially freed”, editorializes The New Times (1/20/2003) while commemorating Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday twelve years after Chsauna’s essay. What does it mean to be partially freed? From the inception of our instrumental classroom, students debated race. Writing fourteen years earlier and just four years into the celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s holiday, students painted striking portraits. Indeed, no one escaped their scrutiny. When there was an attempt to tarnish the image of Dr. King Jr., sophomore Stephanie Noel offered the following piece:

“…. In Memphis, on January 14th, 1989, a calendar was distributed to McDonald’s, which had Dr. King’s birthday as ‘National Nothing Day.’ After it was observed… the management issued a written apology to all employees stating that the calendar entry was a ‘serious negligent human error.‘

This is a total insult to Dr. King Jr’s observance day and all blacks… I think that this is something students should query because we are the future, and we should not allow anyone to try to belittle the dreams, ideals, and most of all the contributions of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” (Crossing Swords, 1989, p. 51).

How then should those partially freed citizens deal with a situation in which the glare of prejudice often contributed to so much discomfort to so many? Is it any wonder then that many students spoke about boycotting McDonald’s on reading Stephanie’s essay? Responding also to the same event, Kevin Cleveland offered “Smash the Gates!’ in which he wrote:

“‘This is a white man’s world.’ Perhaps. And, yes, we must emancipate ourselves from mental slavery. Only through education can we achieve greatness. Black brothers and sisters should come together as one, so we can crack the walls of poverty and smash the gates of ignorance. Take heed brothers and sisters, we must stand together…. Knowing who you are and what you are is very important. For when we know, they can never strip us of our knowledge and our self-pride.”

“A man with a badge has committed a sin…/ And now he hides in the castle of his skin.” David Rudder, “41 Bullets”

Students were uncompromising with their opposition to anything that smacked of prejudice, especially when related to the legacy of Dr. King Jr. Indeed, their high school years were providing them with a forum which, through critical reflection on the then and now, allowed them to discover themselves and each other. In celebration of the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday in 1990 and demonstrating a clear break with the overt bigotry that engulfed celebration of his day in Memphis and other southern states, Ann Marie Green offered [Holiday!]:

“Free in the crowd/Celebrate aloud.

Show triumph!/Go at the privilege given.

Struggles made to bring victory/Let it be known.

Silence is loud as a million drums/Victory need not scream.

The FIFTEENTH day is outstanding/January is fruitful.

The occasion is known/Without songs and speeches.

With tributes/Upside down/Inside out.

No one can deny…/ A Dr. of Luv/King of Peace/

Jr. in his days/A senior champion for all days.” (Crossing Swords, 1990, p. 83).

If Ann, Stephanie, and Kevin spoke in a general sense of the quest for equality, then Chsauna spoke to its denial. As a ninth-grader, she rose to the challenge of writing whenever she had something of substance to say by using writing as a vehicle to relay her thoughts on vexing social and political issues. By so doing, she helped create, as Ann Green, one of her compatriots observed [in the 2000 journal]: “a platform on which many respectfully mounted.” And her writings not only resonate through time but also continually serve(d) as a source text to engage students, parents, and the community at large in what Freire refers to as “a dialectical relation between a reading of the world and a reading of the word.” Indeed, the writing community read “Uniformed Hoodlums in Blue” from different perspectives.

In her senior year, this essay elicited a host of comments. [A] ninth-grader, challenged Chsauna’s views, concluding:

“… I disagree with the article because some officers will go all out to see that the law is enforced. When [ten] year-old Jessica Guzman was killed (disappeared), the police searched desperately, not just to capture Jessica’s killer but for the killer of the other children, who were believed to have been killed by the same person.

Further, when the ‘zodiac killer’ was stalking [California], the police worked ‘round the clock,’ trying to find the killer while at the same time trying to protect everyone. Do these officers seem as if they want to victimize people of color? I don’t think so.” (CS, 1991, p. 118).

Once again, we see the writing community’s fearless nature that evolved as ninth-grade students were neither cowed nor felt any reticence about disagreeing in print with seniors, even venerated ones. Still, other students embraced Chsauna’s seeming call to arms. Writing in the same section that “Uninformed Hoodlums in Blue,” generated Tricia Parris spoke about “Freedom: An Unending Quest,” in which she wrote:

“Although Africans were kidnapped from… Africa, tortured and stripped of human dignity, their spirit was never broken. During slavery, blacks were mutilated and whipped because of their wish to be free. Blacks ran away from slavery, as illustrated by Harriet Tubman. She was not content to be free until her brothers and sisters in bondage were liberated. She skillfully guided many to freedom through the famous Underground Railroad…..

When ‘freedom’ came, we were still marked by the badge of servitude. The legacy of slavery is so terrible that there is still an unending search for real liberty… The American constitution is a diamond in the rough. Every day it is being challenged, and if the Supreme Court judiciously interprets the law, it will be chiseling out ‘precious heritage’ the way a diamond cutter adds the final touch to a precious stone.” (C. S. 1991, p. 125-126).

Thus, the lively and problem-posing forum that they had created allowed them to avoid being wedded to anyone’s view or how issues should be contested. Writing the previous year and responding to a different type of victimization, Chsauna used a … quote, first used as a thought experiment in class, to introduce her essay, “How Many More Must Die?”

“We want justice to roll down like a mighty stream, not like a narrow mainstream.”

“Justice never quite seems to get done the way it should whenever we are too quiet when something unfair happens. We cannot continue to wait for our teenagers to be killed before we show our rage. We cannot wait for another Michael Griffith or Yusef Hawkins to be killed by whites before we act out our outrage. We cannot wait until another Eleanor Bumpers is shot and killed by a white cop before we continue to protest.

How many more of us must die before we realize that the only way to get justice is by being vigilant and militant? We should be grieving the unfortunate deaths of these innocent citizens every day. And each time that we feel this grief, we should start protesting. We shouldn’t stop protesting a week after the funeral or after the many innocent verdicts. We have to show the authorities that we are angry, and we are going to stay angry until justice is done to those who commit these acts of hate against innocent blacks.

We have to stay militant in order to show those cops and others who intend to commit racial acts that we are angry and are going to stay that way until ‘justice rolls down like a mighty stream.’ When we stay that way, the next group of cops or bigoted teenagers who hate blacks or whose gun wants to go off ‘accidentally’ in the direction of an innocent black youth or elder would think twice before they decide to approach us. We must unite and then fight against injustices. The sooner we come together and stay together, the sooner we can make a path towards justice in every way.

I agree with the need for Black Militancy. For it appears that the only time the authorities really try to deal with injustices is when we protest and fight for rights that have been denied. This action also shows unity. It also sends a signal that more or other actions would be taken if we don’t get justice. This is why the authorities are more afraid of African-Americans uniting than anything else. I feel that if we unite all the time instead of only after a tragedy, we will really overcome.”

(Crossing Swords, 1990, pp. 53-54).

Let’s Go Forward

Jose Augustin (Senior)

Let’s go forward my Haitian Brothers/Let’s walk together towards progress/It’s time to show our honor and the honor Of our country…/Let’s work as our old brothers Toussaint L’Ouverture/Jacques Dessalines and many others…/All we need is Unity/Savoir-Vivre and Love…So, let’s get together. Let’s go!!!!

Insert from Crossing Swords, 1990, p. 90

Chsauna’s essay generated seventeen pages of students’ reactions and elicited responses from our extended family beyond the school. Clara Williams, a parent who was not only a staunch supporter of the classroom and journal but was so impressed [with] Jenkin’s essay that she made it her duty to meet Chsauna in person. Responding in a long article, “On Militancy: A Parent’s View” excerpted below, Ms. Williams wrote:

“The depth of understanding revealed by Chsauna Jenkins in ‘How Many More Must Die?’ is astounding to find in one so young. I feel like a mother bursting with pride at how enlightened her children are. I’m happy to realize that their vision is 20/20 and that they are healthy and vibrant and able to deal with whatever the future holds. Certainly, they will have a hand in shaping their future.

After reading … students’ responses to Chsauna’s article, I felt compelled to respond. For, it seems as if many students have bought into mainstream media’s definition of ‘certain’ words. However, we should keep in mind that the word ‘violence’ does not appear anywhere in Chsauna’s article. I believe her call for militancy is the avenue needed to bring about change.” (Crossing Swords, 1990, p. 66).

Here we see the parent joining the dialogue and operating as a key player by having her views factored into classroom debate. What a discussion about the continuing presence of racism ensued in the classroom, hallways and lunchroom, and meetings of the Society For Social Analysis(2)! Extending Chsauna’s analysis, Rosemarie Dunbar offered a powerful piece that she called “Oppression on Fire,” in which she wrote:

“As I sat in front of my television last summer, I saw oppression. I saw my community in upheaval. I saw oppression on fire. A young black man went to Bensonhurst to look at a used car. He never returned (home) alive. Yusef Hawkins was brutally killed by 15 to 20 young tugs. He was killed because he didn’t belong.

In 1988 Michael Griffith, another African-American, was killed because he also didn’t belong in “white” Howard Beach. It seems as if blacks are oppressed and are not allowed to lash out. But if you are born white, it’s your birthright to the stars.

It seems to me that young black men are disappearing. Oppressed young black males have no space in society. In some areas, blacks are not… welcome. To be born Lack in Anglo-Saxon America is a strike against you.” (Crossing Swords, 1990, p. 61).

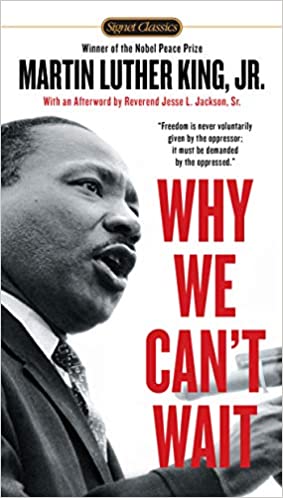

Just as students engaged and contested Chsauna’s views within the school, so too readers outside of the school commented not only on her views but on the discussion that it spawned. In an extended assessment – excerpted below – of the forty-two-page section of the journal– called “Why We Can’t Wait!” James O’Neal, an attorney at law, challenged Jenkins to clarify her views. He noted:

“….Chsauna Jenkins’ (‘How Many More Must Die?’) makes a strong statement for activism among African Americans. She is right in stressing that all too often we as a people react rather than act. Our anger results in protest for a short time but unfortunately is not sustained. Though there must be unified action on our part, the question is in what form should it come? Ms. Jenkins only needs to elaborate on her suggestion of ‘being vigilant and militant.’ Are we talking weapons or constitutionally allowed forms of protest? This is a key question, which must be answered.” (Crossing Swords, 1990, p. 93).

Again we note how, even without being fully conscious of the scope and sequence of our dialogue, we were fashioning an environment in which parents, and other members of the extended community, by commenting on classroom issues not only validated the forum that we were constantly re-creating but sent powerful signals to students that the work they did in the classroom was valuable. Their voices were finding a receptive, though critical, audience beyond the school walls. It’s interesting to note that the willingness to transgress borders was reciprocated on both sides: within the physical classroom and beyond the extended one – the village. In a sense then, by shattering the walls that usually separate the school from its community and by “breaking down the distinction between high and low culture [thereby] mak[ing] the everyday an object of serious study”(Giroux), we may well have been both “rethinking the boundaries of educational discourse”… and refashioning… the very notion of the saliency of students’ lived realities in classroom dialogue.

How, then, did Chsauna Jenkins, at the time a junior, respond to O’Neal’s concerns? Was she resistant to reading seventeen pages of student commentary and four pages of adult responses, especially when there was no “tangible” reward, such as extra credit?

Writing with O’Neal’s question (in italics above) serving as an epigraph of sorts to her essay entitled, “Reflections on ‘How Many More Must Die?’ And Its Critics”, Jenkins noted:

“…With much eagerness, I read students’ responses to my essay and was happy when they agreed with my views and understanding when they didn’t. Some students agreed with me for the wrong reasons, and some disagreed with my views because of misinterpretation.

When I said, in my essay, that we had to fight, I didn’t mean physically; I meant effectively! I didn’t mean that we should go out and beat up whites so that they would know not to mess with us.’ I was suggesting that we should fight verbally; by protesting, participating in rallies and demonstrations, boycotts, and maybe when necessary, to really drive our point home, close down(3) a building or two. When we engage in militant protests, the authorities realize that we want Justice. We want it now!

If the authorities and those who want to engage in acts of rage against us realize that we won’t stop being militant and supporting each other, maybe then they will give us our due –Justice. You can’t just sit around and wait for Justice. You have to demand it! JUSTICE NOW!”

Interactions like this one between Jenkins, fellow students at different points on the achievement and grade spectrum, and Ms. Williams and Mr. O’Neal’s, suggest that classrooms in the humanities, especially social studies, operate best when envisioned as a social laboratory open to parents and the wider community.

And, it is in this sense that we argue that we were, in fact, creating communicative communities across the borders of the classroom, one in which students, parents, and the wider community see “themselves as mutually responsible for the development of a learning community” of seekers, one that’s empowering while allowing the community to “offer constructive input” (bell hooks.) These parents’ and community views are not merely testimonials but an affirmation of a classroom process in which students, by engaging race on the American plantation, refashioned the classroom into a reflective and democratic one.

POSTSCRIPT

June 12, 2020

“A great democratic revolution is taking place in our midst; everybody sees it, but by no means, everybody judges it in the same way.” Alexis de Tocqueville.

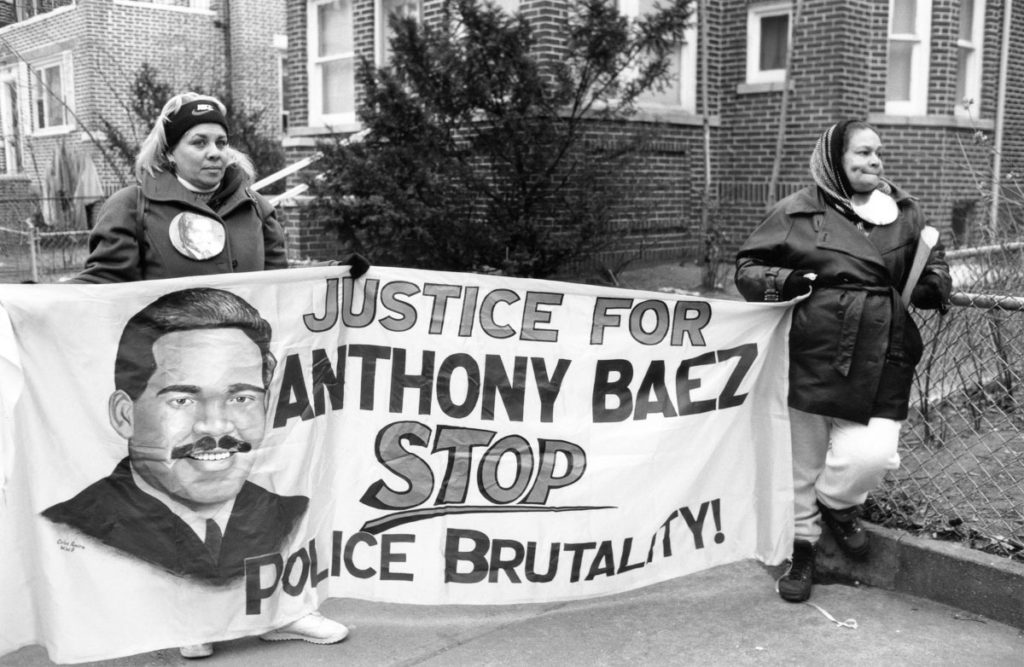

Rereading students’ views from 25-plus years ago underscores Freire’s view that “[w]riting fixes the force of orality in time, but… the text remains alive and unfrozen,” as witnessed by the prescience of students’ words against today’s drumbeat. Indeed, writing against the backdrop of the Uprising in the streets supported by worldwide solidarity to “smash the gates of ignorance” and greed that entrenches racism on the American plantation, there’s a valiant call for social and economic justice, equity, and “legal mechanisms with teeth” to ensure Black Lives Matter. As then 17-year old Anicia Dalhouse affirms, in her 2000 poem, we must keep the flames aglow and “Rise Up Ye Mighty People” so that no more vile acts of brutality are committed, nor immoral not-guilty verdicts handed down from the courts of injustice. In her poem titled, “Uneasy Peace (Not Rest In Peace”), [Dalhouse] writes:

I lay still/ I breathe not.

All I hear is/ Crying around me.

People are saying/ “He got shot.”

My soul rests not.

Now I remember/ The 40-plus bullets that pierced me.

“Amadou!” my mother cries/ But I can’t answer.

I weep inside/ As they put my body

Down the ladder.My soul is haunting me/ Asking why?

As I creep into the courtroom/ I hear the jury say, “Not Guilty!”

I feel another 41+12 shots hit me/ Tears ran down my killer’s face

When he explained/ How he rubbed my face.

But before I took my last breath/ I saw the smirk on his face.

A smile that said/ One by one surely,They’re going to get my race.

My soul weeps/ And tosses and turns.

But my soul gets happy/ As I hearThe valiant voices of my people

Protesting.Protest my people! Protest!

My soul still cries on.

“Amadou!.. Amadou!..”I hear my mother’s call

“Justice! I’m going to get for you,Even if it takes my all!”

I feel tears that want to come outBut it’s too late.

A dead man can’t cry!(Crossing Swords, 2000, p. 123; Classroom Calypso, 2007, p. 328)

End Notes:

- The essay was in part a critique of Shelby Steel’s “A Negative Vote on Affirmative Action,” NY Times, May 13, 1990

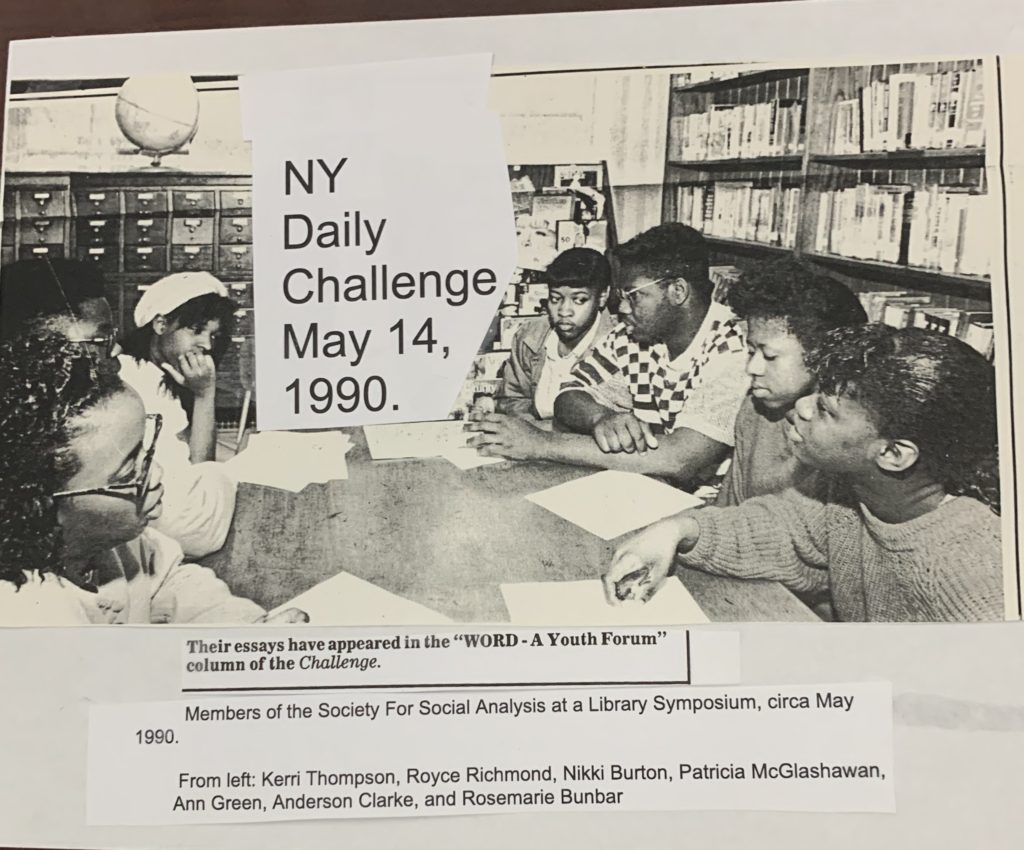

- The Society For Social Analysis (1987-2000) was an after-school organization that founded the journal, Crossing Swords, in which students’ writings were first published.

- In the original version, Chsauna wrote “burn down a building or two” but changed it to “close down” after reflecting on reactions from members of the Society for Social Analysis.

Acknowledgments:

- BDN extends thanks to Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. for permission to republish the chapter and profound thanks to Dr. Shirley Steinberg for facilitating the process.

#PublicSchools #SchoolCulture #StudentCentered #StudentChoice #StudentEngagement #StudentLed #StudentVoice #blackpower #peacefulprotest #humanrights #police #endracism #resist #activism #blm #blacklivesmatter #georgefloyd #justiceforgeorgefloyd #protest #justice #racism #nojusticenopeace #icantbreathe #policebrutality #black #equality #blackhistory #peace #Student(s) #ProjectBased #21stCenturySkills

////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\///////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\/////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

W. R. (troppy) Holder is an emancipated NYC public educator and a founding member of the Caribbean Awareness Committee(NY).