|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 8 mins

February 20, 2020

Preface

In the year 1976, being a History teacher employed with the Ministry of Education in my own Trinidad and Tobago, I was posted to Couva Secondary school in Central Trinidad to teach Caribbean History. At the same time, my friend and teaching colleague, Lance Heath, was posted to Tranquility Secondary school in Port of Spain to do likewise.

One cool afternoon, in 1976, after drinking a few beers on Prince Street in Port of Spain, Lance informed me that he was taking his class to meet Tubal Uriah Butler at Filtration Road in Guapo, near Point Fortin, South Trinidad. Just so, I decided to join my class with Lance’s.

Lance and I were in Teachers’ Training at Government Training College [GTC] in Port of Spain from 1964 to 1965 (I left in 1966), and one of the things we had learnt from Edrick Gift, the lecturer in Caribbean History, was that, in terms of teaching History, it was better to take the class to a person or a historic place rather than engage the students in ‘’chalk and talk’’ and ‘’ole talk.’’

‘’History is a subject,’’ according to Mr Gift, ‘’where children learn much more if they are exposed to the subject itself’’ (Gift, 1964). He would say to us month after month that ‘’Primary school children have not yet reached the age to indulge in abstraction so they cannot easily grasp such abstract ideas as freedom and justice. Hence the more they are exposed to people, things and events, the better they will understand the concepts that History poses (Gift, 1965, p 9). Science lecturer Ms. Eastlyn Bynoe used to say the very same thing to us: ‘’If you want children to understand flowers, don’t draw a big flower on the Board, take them outside to see the flowers’’ (Bynoe, 1964).

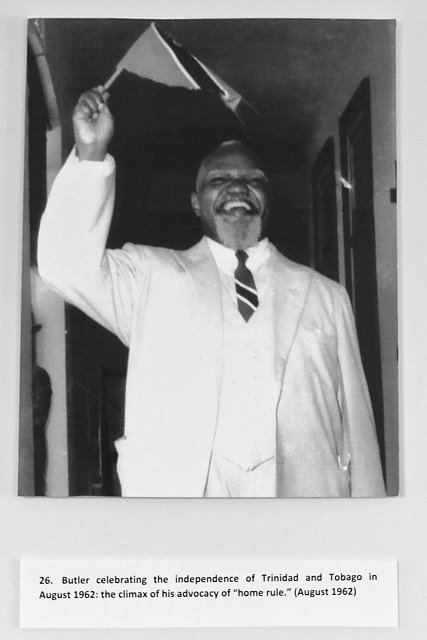

Lance and I decided then to take our history classes (Couva and Tranquility), to meet Tubal Uriah Butler who, at that time, 1976, lived very humbly in a home bought or repaired for him by the Oilfields Workers’ Trade Union in the oil district of Guapo, South Trinidad. This occurred because the Oilfield Workers Trade Union recognized and understood the great struggle put up by Butler in the 1930s and knew for a fact that it was the spirit and thoughts of Butler himself that brought about the start of the Trade Union Movement, despite the organizing skills of Adrian “Cola” Rienzi. Moreover, the Union went further; it put up a statue of Butler at the junction that geographically starts the town of Fyzabad, where Butler himself used to hold his meetings with the people in the 1930s.

At the class conference, a happy Butler informed us, after saying a prayer and a short welcome address, that he was always glad to meet children. Then he posed to the gathering a question: ‘’What theme in History are you studying?’’ Sure of myself and my work in the teaching of History, I informed him that the children had embarked on a two-year programme in Caribbean history. They had left the Junior Secondary stage and were then preparing for the Caribbean Examination Council (CXC) examination for secondary schools, in keeping with the vision of the Ministry of Education in Trinidad and Tobago.

As such, I went on to say, ‘’we have started with the history of our Indigenous peoples: the Amerindian society.’’ Like a knife cutting through a cake, Butler ripped into me principally: ‘’Teacher, History must start with Butler. The history of Trinidad and Tobago must begin with Tubal Uriah Butler.’’ For a full minute, I froze. Lance, stupefied, bowed his head. The gathering looked at me for help. I therefore informed Butler, in a sort of defeatist mode, that he and his role in the 1930s formed a major part of our Caribbean history and that we shall place more emphasis on that section in the future.

I assured him, although I didn’t know what I was saying, that in the future, History will start with Butler. To that statement, he nodded in agreement and he seemed by his facial twist and smile, to forgive my ignorance.

It was in my class in the teaching of the social sciences at the University of the West Indies (UWI) while reading for my Diploma in Education in 1977, that the principles of education exposed me to the work of Jerome Bruner and his idea of the Concentric Method in History teaching.

According to Bruner, a teacher can start anywhere or on any theme, but he or she must, after circling the many themes of the curriculum, return to the central area where he/she started. Bruner emphasized that the concentric or spiral method meant organizing the curriculum by laying out basic concepts, covering other related materials and then circling back around the basic concepts and filling them with more complexity and depth.

Thus, one can start with Butler, make the whole circle of events in the Caribbean throughout history and return in the end to Butler, at the same time showing how Butler influenced all the events, happenings and challenges that occurred throughout the circle. As in social science, it can be done also with the other natural and biological sciences where fundamentals can be regularly revisited, deepened and broadcasted each time, thereby leading to a better understanding of a subject’s interconnections.

Jerome Bruner posited three stages in his concentric method of teaching. First the Enactive, whereby you aim at satisfying the learner’s interest on the theme or subject; Second is the Iconic, whereby the teacher manipulates images of these objects or processes; and Third the Symbolic, whereby abstract representations of them can be utilized. At the Symbolic stage, data is stored in the form of a code or symbol such as language (Bruner, 1966).

Jerome Bruner then, was a cognitive psychologist who created a theory of development based on the idea that education should be intellectual development as opposed to rote memorization of facts. He stressed learning by discovery and died in New York in 2016. Both he and Butler motivated me during my secondary school teaching at Couva and at Mucurapo.

With Butler in mind in the 1970s and with his passing in 1977, I felt compelled to tell the nation’s youth more of his contribution to our history and society, so that they can begin the study of our Caribbean by starting with Butler; I felt compelled to tell them about the concentric method of teaching history. It was my feeling then, and more so now, that even if teachers did not start the history of the Caribbean with Butler, his campaigns, his speeches and his struggles for Trinidadians in particular ought to be stressed more in the classroom, especially because Butler went to prison unwarrantedly and ought to have been better esteemed and cherished by the British after the elections of 1950, when his party won eight seats to the Legislative Council.

Lance Heath used to say: ‘’If we spend or gain a penny on our salary in the 1970s, Butler is responsible for a cent’’ (1977). It so happened that Butler passed on to his eternal reward on the day of the Dimanche Gras in 1977, motivating me to sing on that very Dimanche Gras night the extra coda/montuno line: ‘’Tubal Uriah Butler wherever you lie/ To your memory I dedicate this cry.’’

That was how I ended my contribution that fateful night. Needless, to say, the crowd roared with delight and I vowed and promised my God, in thanksgiving that night, to write about Butler. I won the Championship Crown in calypso that night; I won Butler over to the cause of history.

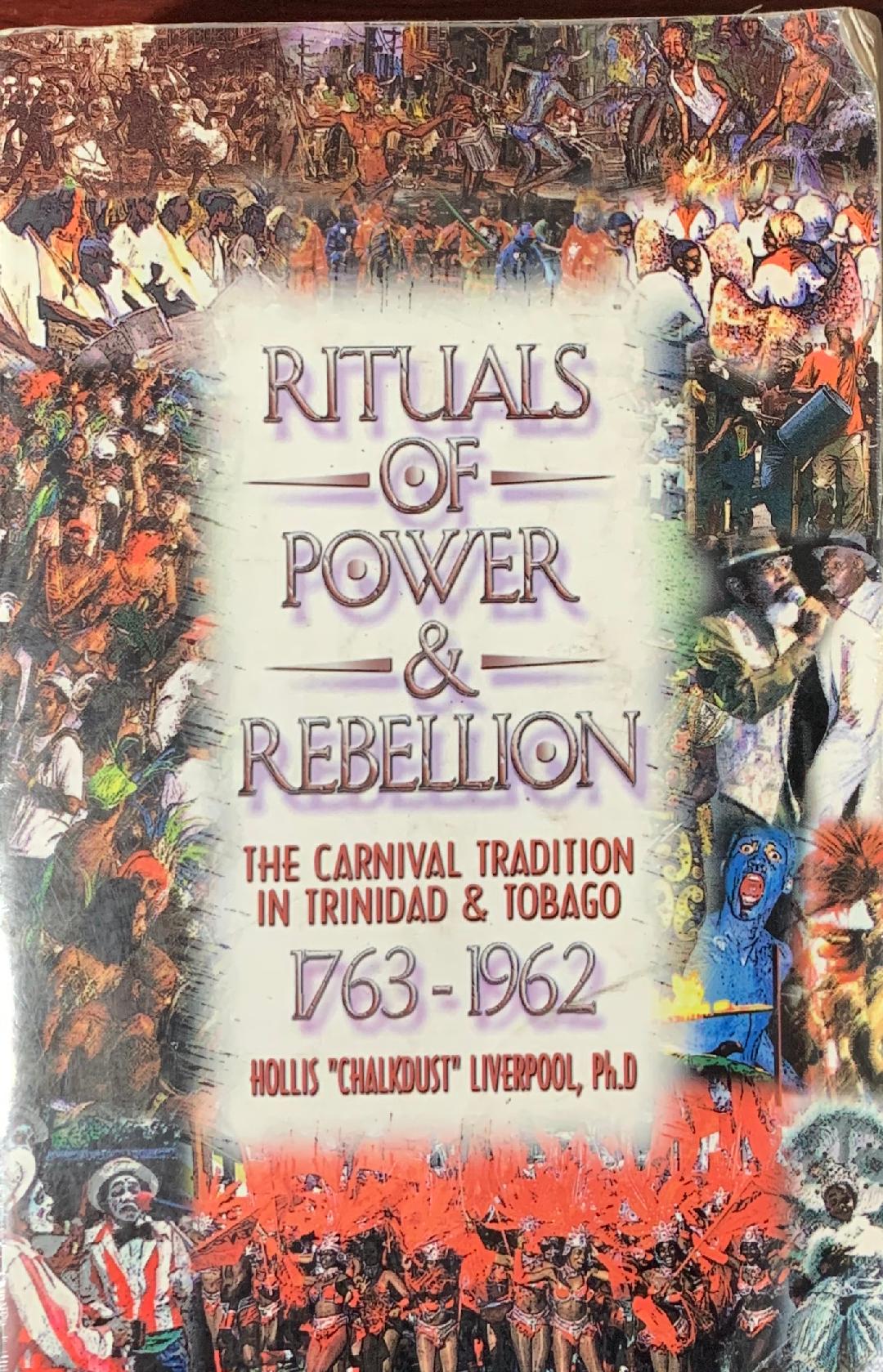

Now that we have moved into the 21st century, I feel it is my duty to show to readers, especially teachers, how the British colonials, represented by the Press, the Police and the Judiciary unfairly treated Butler. It is my duty as a historian to close some of the gaps in our history and, above all, it is my duty to show our people the sufferings of our ancestors during the age of British colonialism. To do so, I have termed the exercise ‘’God, The Press and Uriah Butler.’’ Read not, gentle reader, to condemn or to find fault in, but to weigh and consider.

In education, enjoy.

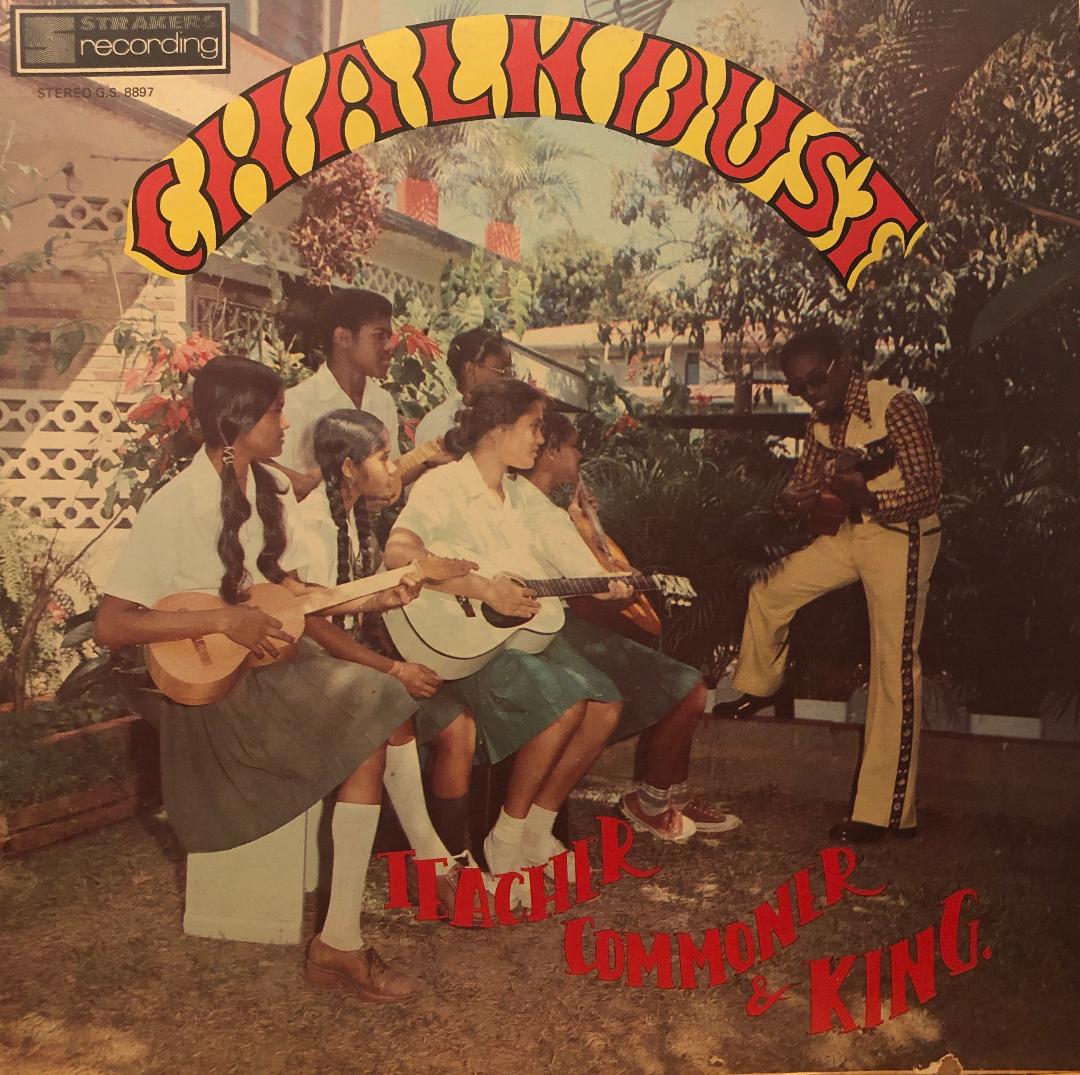

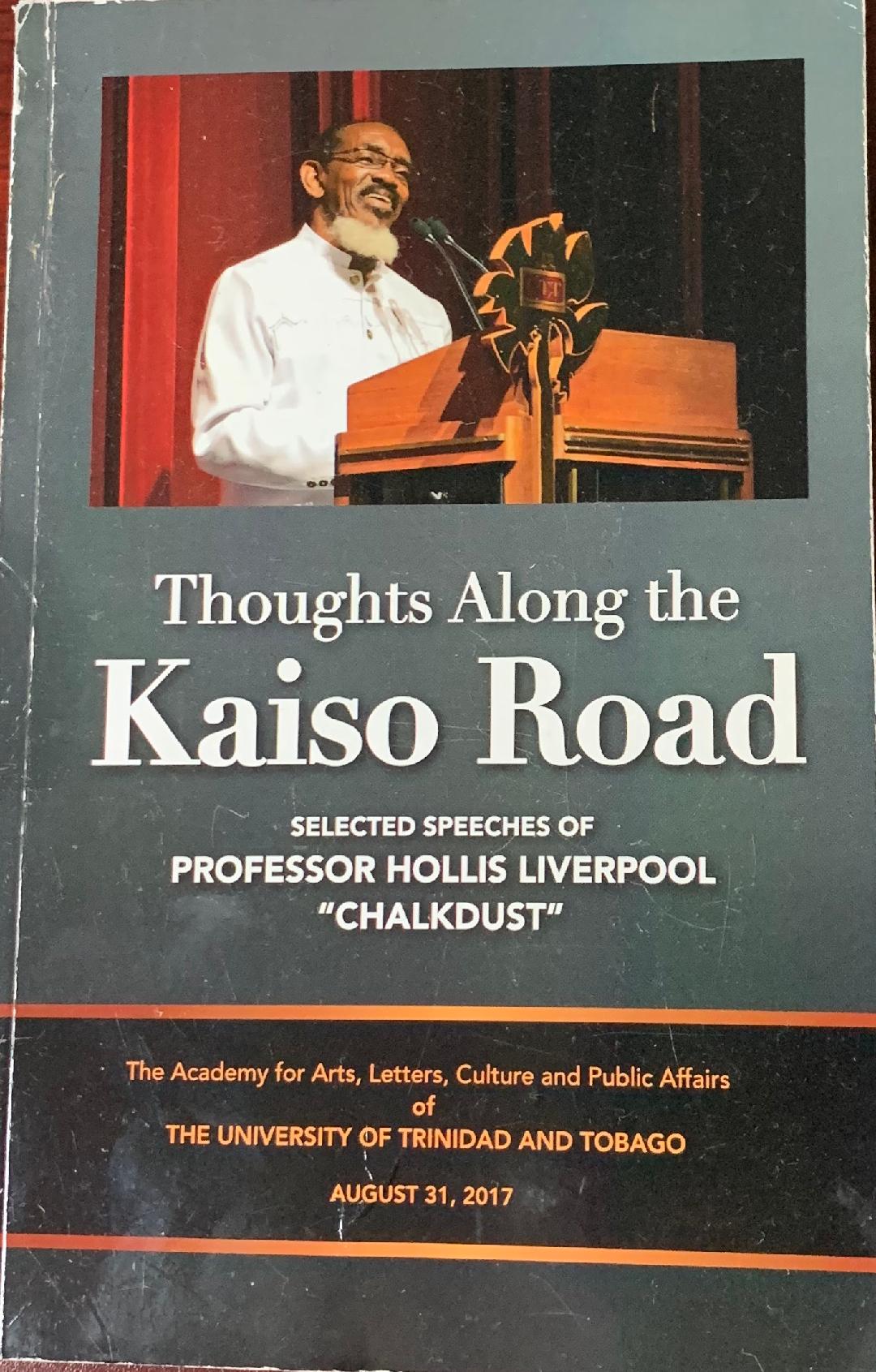

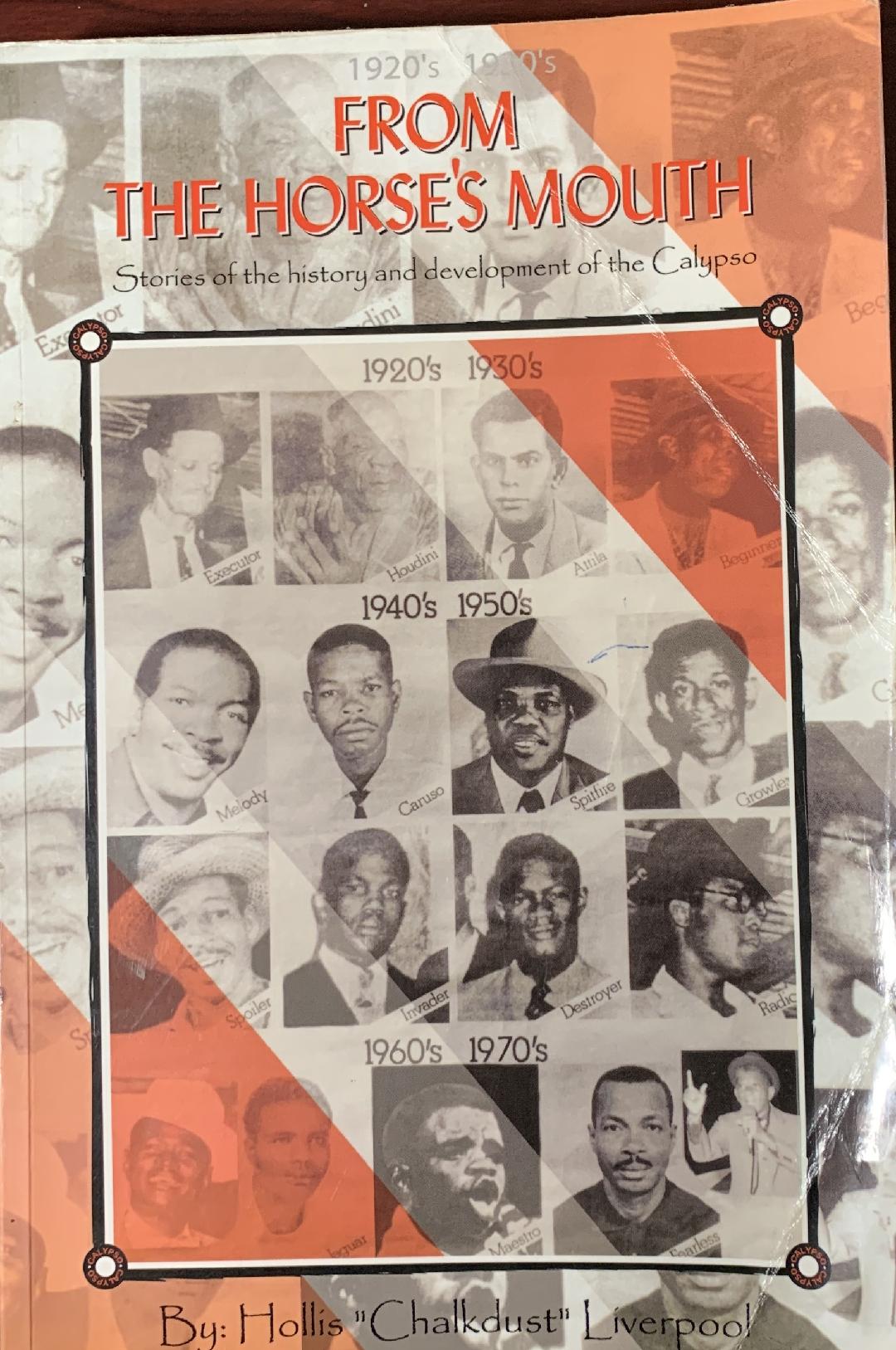

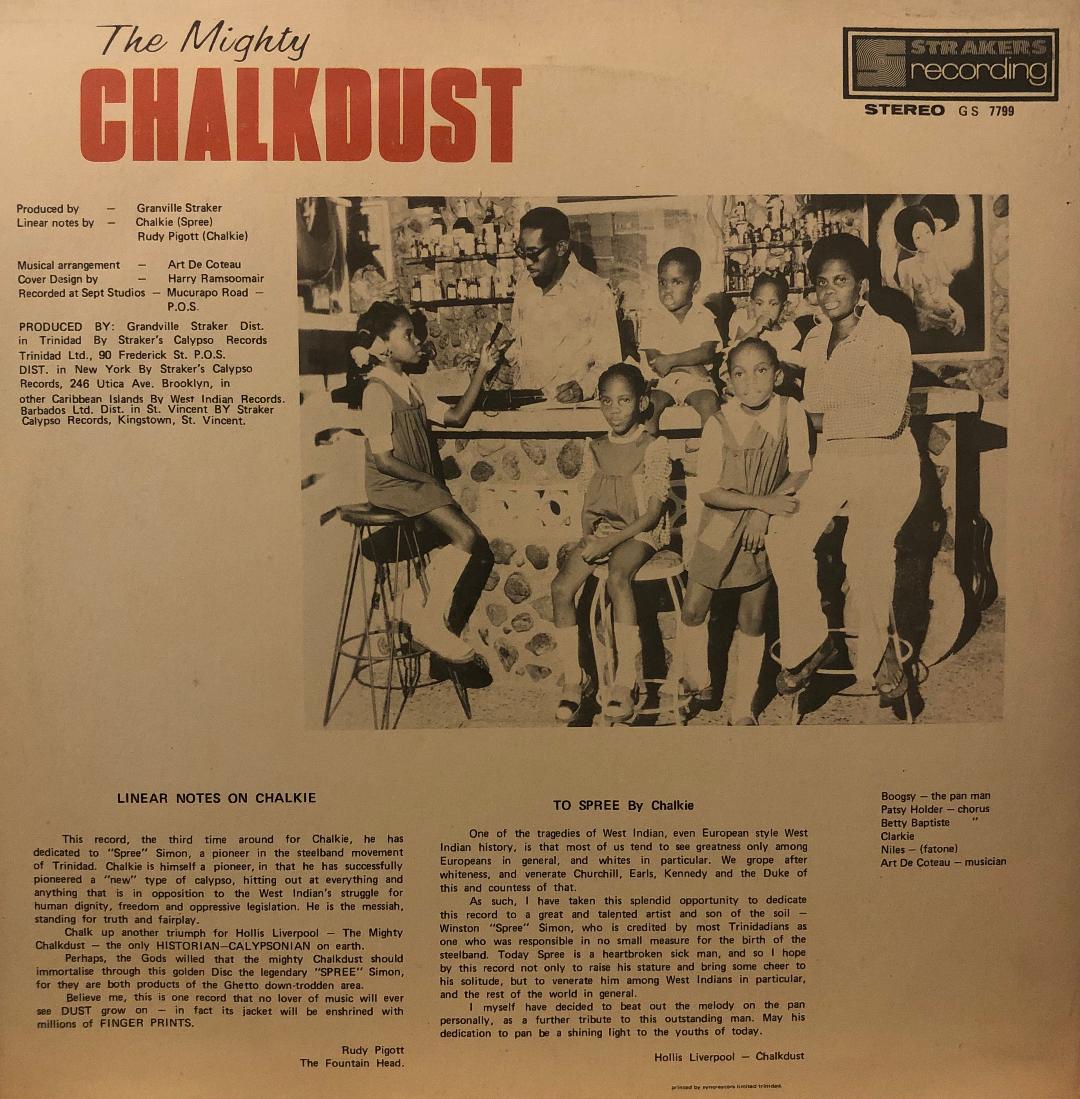

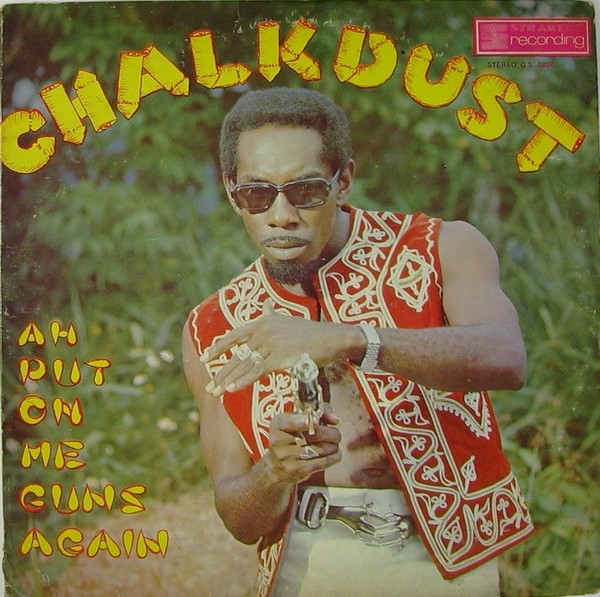

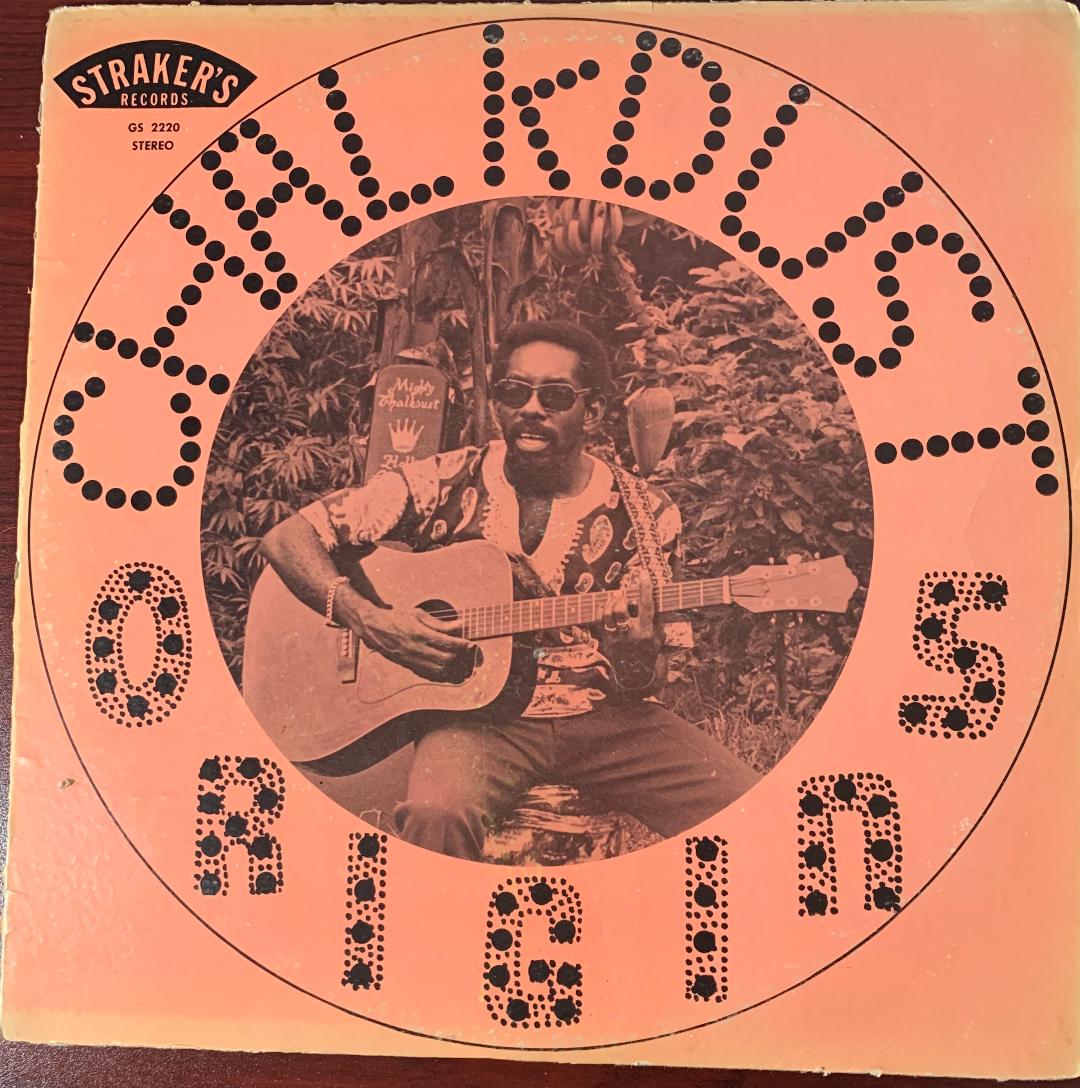

Hollis ‘’Chalkdust’’ Liverpool.

*BDN expresses thanks to Dr. Hollis (Chalkdust) Liverpool for allowing publication of his Preface to a longer work, which is forthcoming.

Works Cited

Bruner, Jerome. Toward a Theory of Instructions. Cambridge, Mass. BelKapp Press. 1966.

Bynoe, Eastlyn. Lecture on ‘’The Teaching of Science.’’ Gov’t Teachers College, October, 1964.

Gift, Edrick. ‘’Lecture on Senior Methods in Primary School.’’ Gov’t Training College, POS., Trinidad. September, 1964.

Gift, Edrick. ‘’The Teaching of History in Primary Schools.’’ GTC 1964-65 Annual Review. POS. September, 1965.

Heath, Lance. Personal Conversations. Four-for-a-Dollar Bar, Edward Street, POS., 1977.