|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 1 mins

Excerpt of a February 5th cyber chat, on the meaning of independence, with Merle Collins, the renowned Grenadian writer, in which she reflects on Kamau Brathwaite’s seminal work on ‘nation language.’

BDN: If the advancement of literacy was a key goal of the revo–and even today– why then should authors privilege creole/nation language in their writing?

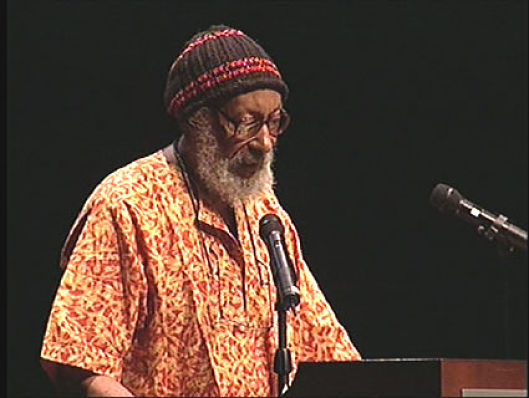

MC: This is a great question to think about just at the point when one of the great advocates of nation language (Kamau Brathwaite), has passed on. Brathwaite, a revered and thought-provoking Barbadian writer, died today, February 5, 2020. Of what he termed “nation language”, Brathwaite wrote:

It is the nation language in the Caribbean that, in fact, largely ignores the pentameter. Nation language is the language that is influenced very strongly by the African model, the African aspect of our New World/Caribbean heritage. English it may be in terms of some of its lexicon, but… in its contours [its rhythm, its rhythm and timbre, its sound explosions,] it is not English, even though the words, as you hear them, [might] be English to a greater or lesser degree.’

Brathwaite, “Nation Language.” Lucy Burke, Tony Crowley & Alan Girvin, The Routledge Language and Cultural Theory Reader. New York & London: Routledge, 2003, 313).

Language is a key player in the transfer of colonial ideas and knowledge shaped by the colonial experience. As a colonial language, English is one of our linguistic experiences, but it is not the only one. Caribbean Creoles carry vibrant histories. Teaching people to value Creole languages and teaching literature in Creole along with whatever the colonial language is – French, Dutch, English – would be a key part of an approach to post-colonial becoming.

Clip of a February 2nd, 2004 Brathwaite Interview with Leonard Schwartz (host of Cross-Cultural Poetics)