|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 3 mins

In a performance of his poem, Kumina, Edward Kamau Brathwaite, counts consecutively and deliberately, the days and the activities encompassed in this spectacle of loss. Grief is laid bare, in words that are hauntingly plain and emotive, as the speaker comes to terms with the death of a beloved. The poem ends in an African chant that is at once an invocation of the ancestral spirits and a profound benediction of mourning.

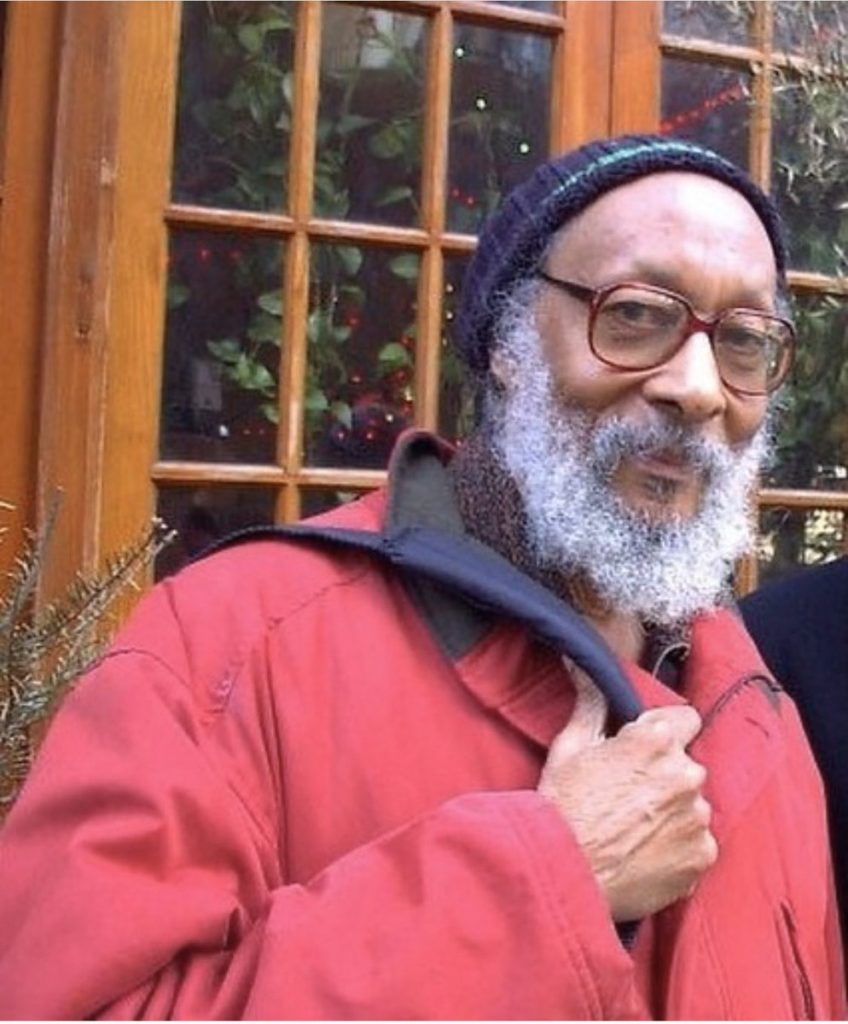

Since Brathwaite’s passing on February 4, eulogists, in their grandiloquence, have spoken of his intellectual prowess and his contributions to the arts, the fashioning of a Caribbean identity and to the canon of Literatures in English, in general. Despite the accolades bestowed to Brathwaite as an academic, poet, historian and playwright, unfortunately, he is an unfamiliar name in the region, and sadly, in the country of his birth. In the heart of Bridgetown, the architectural anomaly of the Round House, a brightly painted, rounded dwelling with no right angles, occasionally proffers a quizzical glance from passersby; but few Bajans know that it is the birthplace of one of the nation’s greatest sons.

Lawson Edward Brathwaite was born on the island of Barbados, a decade before the start of World War ll. For centuries, the colony, an exemplar of the British Empire, has alternated between the cherished monikers of “Little England” and “Bimshire”. Brathwaite, the son of working-class parents, was educated at two of the most prestigious secondary schools on the island, founded for the children of the plantocracy and the progeny of the British civil service class. In 1949, having gained a national scholarship, he immigrated to the “Mother Country”, to begin what would be a life-long educational and experiential odyssey crisscrossing continents, oceans and seas. Although Braithwaite was bred and steeped in all the accoutrements of British colonialism, he would choose not to become an Afro-Saxon; instead, foregoing his colonial heritage to become a disrupter. Over the decades, Brathwaite would accrue a doctorate degree, scores of prestigious awards and international recognition; yet he would remain unabashedly African-centered and proud of the region from which he came.

Brathwaite’s intellect and creativity have never been in question, but the craggy beard, the African garments, the ubiquitous “Rasta” tam, did not conform to the criteria of colonial respectability. He was too authentically a man of the soil, for his own people to embrace, in his youth. With the advent of the Caribbean Examination Council, there was a mandate for a more regional test (than the British GCE) for Caribbean students of English Literature. Yet over the past decade, only two of Braithwaite’s poems have been included in the CXC syllabus. It is interesting to note the frequency of Derek Walcott’s works, one of Brathwaite’s contemporaries, in the CXC’s course of study.

Now, there seems to be a conscious retelling of Brathwaite’s biography with no mention of the oppositional forces that were at work against him in his professional and personal life. In a 2010 article, entitled Cultural Lynching, Brathwaite explains that he had been subjected to an “… artistical/intellectual/spiritual/emotional version of the physical hanging/burning/castration of the thousands of black mostly men that took place here in the USA during the post-slavery period of ‘Reconstruction’”. In the same article, he bemoans the theft of decades of archival materials including manuscripts, personal items, photographs, diaries and letters from his apartment. He states, they were …”stolen by jealousy and envy and by the same mindset that organised the slave trade and teef my culture once before into plantation slavery and now again in New York City in the 21st century.” He and his wife were unable to travel to Barbados to celebrate his 80th birthday, for fear that what was left of his archives would be lifted in their absence. For years he fought a protracted battle with the Barbadian government who confiscated a portion of the land at his famed residence, “Cow Pasture” to construct the new highway. It is not farfetched to infer that Brathwaite’s themes of dislocation; exile; longing; separation and unification; and the historical and contemporary experiences of people of the African diaspora were always present in his life. When Brathwaite introduced the concept of “nation language” as a viable vehicle for transforming the colonialized psyche, the English language purists pushed back. Braithwaite contended that the linguistic mosaic of broken English and African syntax was more than a dialect, but a language onto itself, that could occupy the same space as the Queen’s English. He connected the cultural threads of what he saw as “Plantation America” to “Plantation Caribbean” to the music and rhythmic sounds of the African continent. While visiting Kenya in 1972, the mother of Kenyan writer, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s bestowed the name Kamau (Quiet Warrior) on Brathwaite.

On May 29, 2020, UWI, at Cave Hill, will commemorate Brathwaite’s 90th birthday by dedicating a space, to be known as ‘Golokwati’, after a village in Ghana, where he lived. Brathwaite described it as one of the last “human places” the enslaved Africans rested, before being transported to the New World.

Margaret Prescod-Cisse is a Barbadian, who occasionally writes.

/////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////////////////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\////////////////////////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

“Brathwaite Inspires Still” – Carlyle G. Leach