|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 7 mins

What is the meaning of independence? Big Drum Nation sat down for a cyber chat with renowned Grenadian writer Merle Collins, someone who has spent a lot of time thinking about Grenada and the psyche of its people.

Big Drum Nation [BDN]: It has been 46 years since achieving independence from Britain. What would you say are Grenada’s highest and lowest moments in these 46 years?

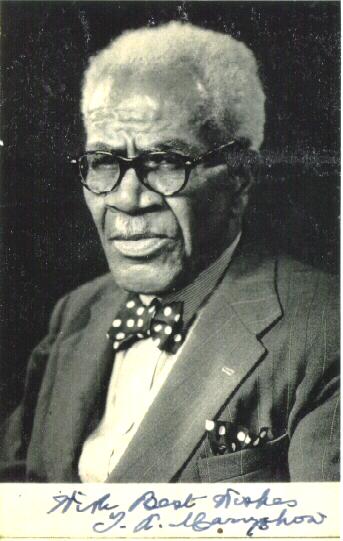

Merle Collins [MC]: Each time I consider Independence I remember the struggles of T.A. Marryshow and others for a Federation of the West Indies. It’s the past, but as we think of the seemingly impossible configurations of the future, perhaps some focus on that period of January 1958 to May 1962, and the colonial impact on the shaping of Grenada and the contemporary Caribbean, remains appropriate.

Grenada was deep in internal political conflict on its day of Independence, February 7, 1974. While the fact of Independence from the colonial power – in Grenada’s case Britain – should be something to celebrate, the memory of the day should be for Grenada a time to reflect, particularly on politics and society and the major individuals, organizations, and parties that have had influence on the political shaping of the country over the years. “Independence” is not, in my estimation, the triumphant raising of a flag and the nostalgic sound of the singing of an anthem.

For Grenada, Independence Day itself was a high and low moment, a conflictual celebration of the notion of freedom. For some, it was an unease about the walk into a notion of freedom. Perhaps we should accept it as conflictual, and try to interrogate the meaning of the moment and the period, even as we celebrate or critique (and, as thinking beings, it seems to me appropriate to do both or either) the first Prime Minister, Eric Matthew Gairy.

During these 46 years, there have been other high and low moments in Grenada’s history, and the moments have seemed high or low depending on political perspectives and, sometimes, individual experiences. 1979, the revolutionary “moment,” was a “high” especially for the largely youthful population, the promise of a politics different from that of the colonial era; for some, it was a “low,” a disappointment that the old order had been challenged.

1979 to 1983 was a mixed period, highs and lows, excitement, disappointment, progress, imprisonments, anxiety. October 1983 was, in my estimation, a decided low, as political leaders stumbled into lack of accountability. The lows of that moment were internal party conflict, murders of citizens and some of the state

Grenada born Theophilus Albert Marryshow, affectionately known as the Father of West Indies Federation

and party political leadership at the fort in St. George’s. The invasion by the United States of America was regarded by some as a “high,” by others as a “low.” It seemed to me that the invasion presaged a movement into a new kind of colonial relationship, a psychological dependence and, for some, a malaise, that has an impact on the post-1983 period.

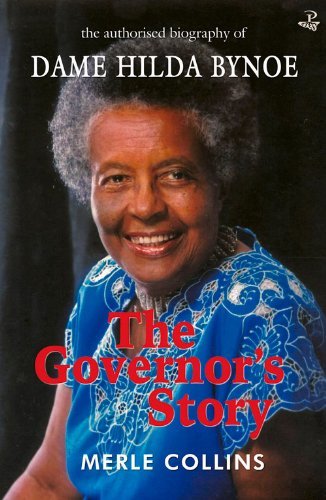

BDN: …In Angel you followed the lives of Grenadian people as they struggle for independence through the eyes of Doodsie and Angel, her young daughter. How important was it for you to center women in this way?

MC: In my writing, I find it important to center life, although the form of the writing might change, and it seems to me that women, as watchers, as shapers, as people who sometimes comment quietly and have an effect on things even when they do not seem to be in the forefront, are an important part of the interrogation. In my own youth, women were powerful, though not public, political forces, and that had an impact. Women continue to be powerful, in or out of political office, so that remains important to my imagining of Grenada’s political realities, at home and abroad.

BDN: … How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction in your narratives?

MC: In one of my poems, “Crick Crack,” the poetic persona asks, “Do we know what is truth, and what is truly fiction?” In my writing, that question often appears in one form or the other. I am fascinated by the idea that people are sometimes guided by different ‘truths’. My writing, I think, often wrestles with the idea of truth. At least, the struggle is there in my imagination. In the Caribbean and the wider Americas, we are people whose societies were created by the example of other people’s truths, of what was right and beneficial for Dutch, French, British, Spanish, and Portuguese colonial powers. That seems to me to suggest that the creation of truths beneficial to us in Grenada and the rest of the Caribbean might necessitate an upending of much that we inherited. As I grapple with these issues, it seems to me that inherited “truths” are often a fiction.

BDN: Is literature really a more powerful/effective tool/form to grapple with/shed light on complex political issues?

MC: I think there are different tools. Literature (and here I think creative writing – fiction, poetry) is certainly one of them. For me, it is effective because fiction allows us to create characters, to imagine situations sometimes based on our everyday experiences, sometimes moving out of the realm of our everyday experience to imagine futures. I think we can grapple with a lot of complexity there. Poetry, too, I find effective. But I also value the essay. I know that Political Science is effective. So here, then, I wouldn’t say “more powerful.” Literature might be more powerful for some and is certainly effective, but I wouldn’t be prescriptive about it.

BDN: Shalini Puri has described Angel as a “comment on academic discourse and political theory”. In what sense does this characterization capture the frame of your novel and, if it does, why was it conceived in such a form?

MC: In that analysis, I believe that Shalini Puri was also considering some of my comments about the process in the writing of the novel. She looked at the fact that the novel foregrounded the voices of people whose knowledge seemed not to be legitimate quotable sources for the political science thesis I was also writing at the ti me of working on the novel. The voices could be given free rein in a novel that could invent its characters and have a discussion in the language of Grenadian people. So yes. In that sense, the novel made comments about use of language, identity, social, cultural, and political power. Later, when some people told me that the voices of the novel were voices they

me of working on the novel. The voices could be given free rein in a novel that could invent its characters and have a discussion in the language of Grenadian people. So yes. In that sense, the novel made comments about use of language, identity, social, cultural, and political power. Later, when some people told me that the voices of the novel were voices they

could recognize and hear when read to them, but not necessarily voices they could easily read, I reflected on language and colonialism, language and power, language and identity, and, of course, language and colonial education. And that’s how I wanted to write the novel – that’s how I had to write the novel when the characters presented themselves – reflecting the voices of the people occupying it.

BDN: If the advancement of literacy was a key goal of the revo–and even today– why then should authors privilege creole/nation language in their writing?

MC: This is a great question to think about just at the point when one of the great advocates of nation language (Kamau Brathwaite), has passed on. Brathwaite, a revered and thought-provoking Barbadian writer, died today, February 5, 2020. Of what he termed “nation language”, Brathwaite wrote:

It is the nation language in the Caribbean that, in fact, largely ignores the pentameter. Nation language is the language that is influenced very strongly by the African model, the African aspect of our New World/Caribbean heritage. English it may be in terms of some of its lexicon, but… in its contours [its rhythm, its rhythm and timbre, its sound explosions,] it is not English, even though the words, as you hear them, [might] be English to a greater or lesser degree.’

Brathwaite, “Nation Language.” Lucy Burke, Tony Crowley & Alan Girvin, The Routledge Language and Cultural Theory Reader. New York & London: Routledge, 2003, 313).

Language is a key player in the transfer of colonial ideas and knowledge shaped by the colonial experience. As a colonial language, English is one of our linguistic experiences, but it is not the only one. Caribbean Creoles carry vibrant histories. Teaching people to value Creole languages

and teaching literature in Creole along with whatever the colonial language is – French, Dutch, English – would be a key part of an approach to post-colonial becoming.

BDN: …How significant was the transformation/indigenization of carnival during the revolution in contributing to a Grenadian aesthetic?

MC: Very significant. Valuing what you have, and understanding how what you have on the cultural front contributed and continues to contribute to what others have, is important. Valuing self, and celebrating our own creativity and exploration, is not diminishing the other.

BDN: The motto/slogan for this year’s independence commemoration is “Preparing for the future through empowerment, growth and long-term sustainable development”. What are some of the basic requirements for Grenada to achieve these goals?

MC: I hope some of what I’ve already said – answers given to other questions – points toward what I consider important as we are “preparing for the future.” We are always doing that, and the mind, our attitude to ourselves … individual, country, nation, region, is important. We still have a lot of work to do on the psychology shaped by colonialism.

BDN: In 2015 the Temne people of Carriacou and their African roots brothers and sisters of Sierra Leone reunited in ceremonies on that sister island. We are also seeing the revival of indigenous traditional African-retentive mas, such as Viecoux. And, as you have documented, the practice of saracca is regaining appreciation nationally. As we reflect on Grenada’s independence, how important are these elements of our history and culture in forging national consciousness?

BDN: In 2015 the Temne people of Carriacou and their African roots brothers and sisters of Sierra Leone reunited in ceremonies on that sister island. We are also seeing the revival of indigenous traditional African-retentive mas, such as Viecoux. And, as you have documented, the practice of saracca is regaining appreciation nationally. As we reflect on Grenada’s independence, how important are these elements of our history and culture in forging national consciousness?

MC: Very important. As we reflect on independence, we reflect too on culture and society, on the life’s work of someone like Winston Fleary (recently deceased), and on all that our colonial education taught us was unimportant.

BDN: What is the role of culture and the arts in shaping national consciousness?

MC: Culture and the arts have a key role in the shaping of national consciousness. They are not an extra bit to spice up a presentation. They are – or should be – centre stage in the shaping of national consciousness.

BDN: Thank you…

Independence is not an event. It is, like all of our history a process; a continuum of present,past and future.

That is how all history of mankind is.

For those of us who have emerged from the colonial experience, it is important to understand how it influences our present.

From the perspective of both coloniser and colonized, there have been influences and we must be aware of and examine all sides.

Whether as individual nation states or as a Caribbean region, we must interrogate our present and understand the influences of our past as we shape our future.

It is necessary to include all our region and not leave out those who emerged from the Spanish imposition as well.

For us in Trinidad and Tobago, we beginning this February month are marking 50 years of the 1970 Revolution.

We must examine its “highs and lows” as Ms. Collins put it, and from whose perspective and why.

That moment too constitutes a development in our nation-building project- the Trinbago as well as the Caribbean project.

We must commemorate, celebrate and evaluate each such moment as individual ‘territories’ and as the Caribbean collective.

For us in countries labeled (by self and others) as multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multi-cultural, there is particular importance for understanding “valuing self and celebrating our own creativity and exploration” as well as that of each other.

If we cannot do that without feeling threatened by each of the multis doing so or threatening others by our own self-examination, we cannot forge a future that we all create.

This is vital for “territories” like Trinbago and the Caribbean as well.