|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 9 mins

[I of V]

Big Drum Nation’s Introduction

August 23, 2019

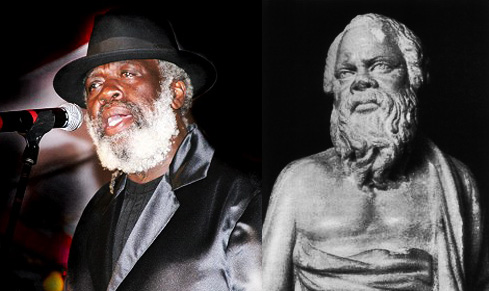

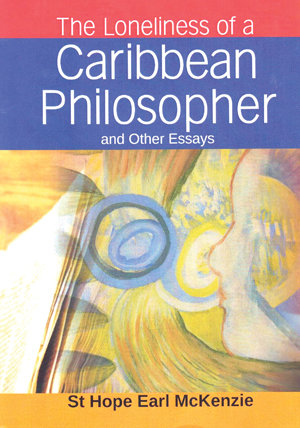

“The Caribbean may well have produced [a Socrates, Descartes or Spinoza], but I am not aware of any records of their thought.” – St Hope Earl McKenzie, The Loneliness of a Caribbean Philosopher.

“I come from the land of the giants…/The land where these giants walk/Despite the stings and the arrows/When them boys walk, they cast a long shadow.” –3Canal, “Giants”

“This is our symbol–Beauty famous in the slum/The hungry boy who/Tomorrow shall become/The country’s hero.” – Eric Roach, “The Flowering Rock.”

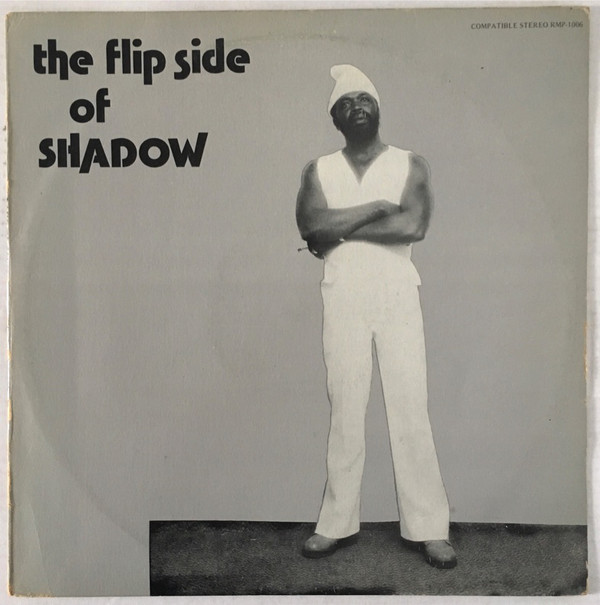

I. Shadow and ‘Self-Acquired Knowledge.’

“You are not a fan, you are a fanatic!” was Shadow’s response to my question about the inspiration for his line, “Their minds are like factories/producing misery” (‘Grooving Time,’ 1976). So, in that chance encounter at Charlie’s Records in the summer of the early 1980s, I thought I’d engage him around those lyrics that had always intrigued me. Not even Charles Dickens in Hard Times or Karl Marx in his flailing of industrialization seemed to have been able to pare down the horrors of the factory system with such sharp irony as Shadow had in a visionary and seemingly throwaway line. Still, his spontaneous and somewhat paradoxical retort fascinated me even more.

This deep interest in Shadow (who never used the moniker “The Mighty”) and his world/work had intensified after reading Linden Lewis’ “The Mighty Shadow on the Pointlessness of Human Existence” (Caribbean Review, Vol. X, No. 4, Fall, 1981) in the early 80s. Such a classic misreading of the Dreadman’s work troubled me.

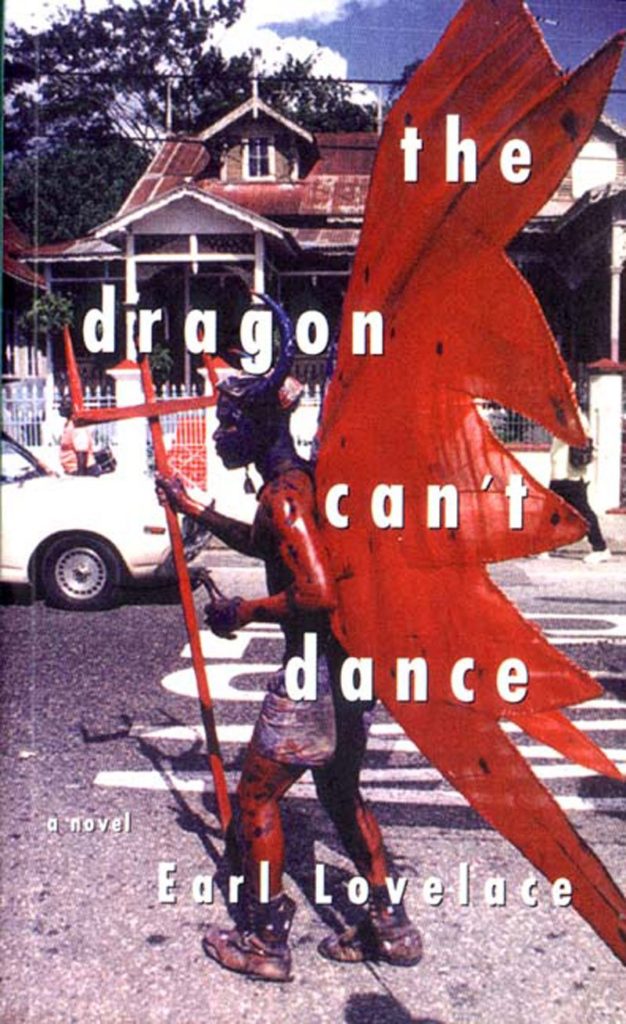

Lweis’s corruption really—dissing–of the Dreadman’s work repulsed me. However, accepting Earl Lovelace’s critique of professors who, in interrogating the calypso, silence calypsonians’ voices beyond the lyrics—even to the exclusion of meaning to the artists as with the revelation of Philo, the calypsonian, in The Dragon Can’t Dance, “…It was a nice article, and he had cut it out and put it into his scrapbook… He wasn’t sure if he understood the professor.“—I began embracing the notion that ‘text without context is pretext.’ Hence, I thought of engaging Shadow to see if I could get a bit more source text to understand better/situate his lyrics.

And there I was with Shadow, questioning my questions and challenging me to figure out his work by engaging the Calypso and its literature. His semi-dismissive response to my initial inquiry left me with a lifelong quest to try to come to terms with the philosophical Shadow.

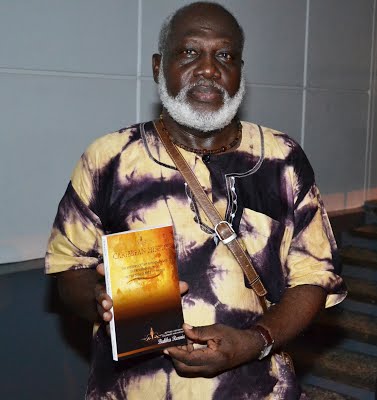

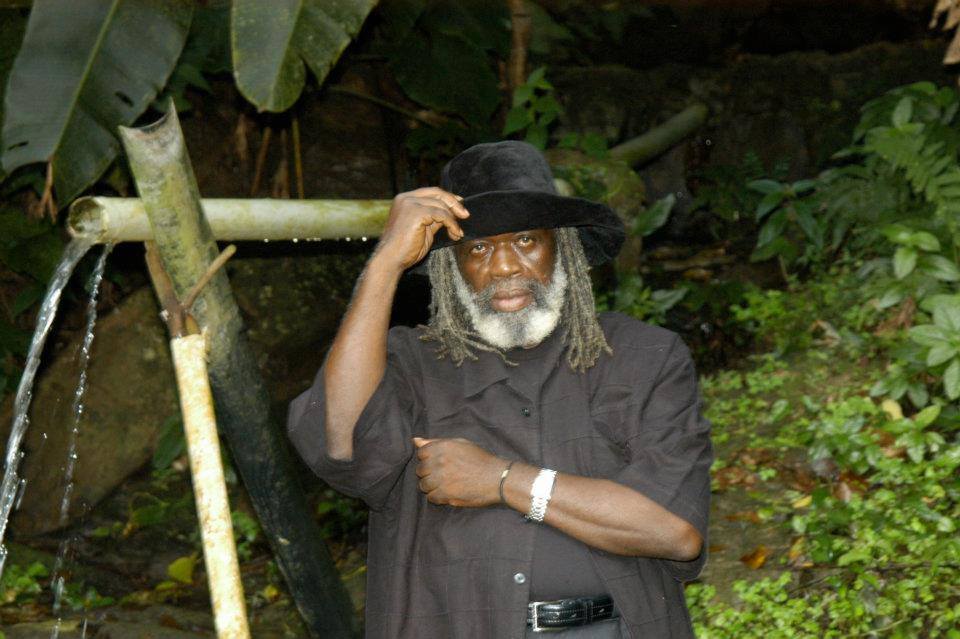

Bukka Rennie is an activist, historian, and renowned calypso commentator.

Shadow is, as Kim Johnson suggests, “enigmatic and other-worldly, really like a jumbie come down to teach us…” (personal communication 7/28/2008) about navigating the reality of our existence. Shadow and his haunting, polyrhythmic riddims and melodies often incite more moves in us than a drunken sailor exhibiting/displaying more shades and sides than a rainbow. Our Sage is multidimensional as his phenomenal output straddles many philosophical strands and may best be revealed through the prism of the Ancient Indian parable about the elephant and six blind men, in which each touches a part of the elephant and tries to convince one another that what each felt captured the entire picture (Indeed, Kenneth Ramchand’s “Partial Truths: A Critical Account of V.S. Naipaul’s Later Fiction” (1984), provides a timeless and critical cross-disciplinary disposition worthy of embracing when engaging texts in the humanities.)

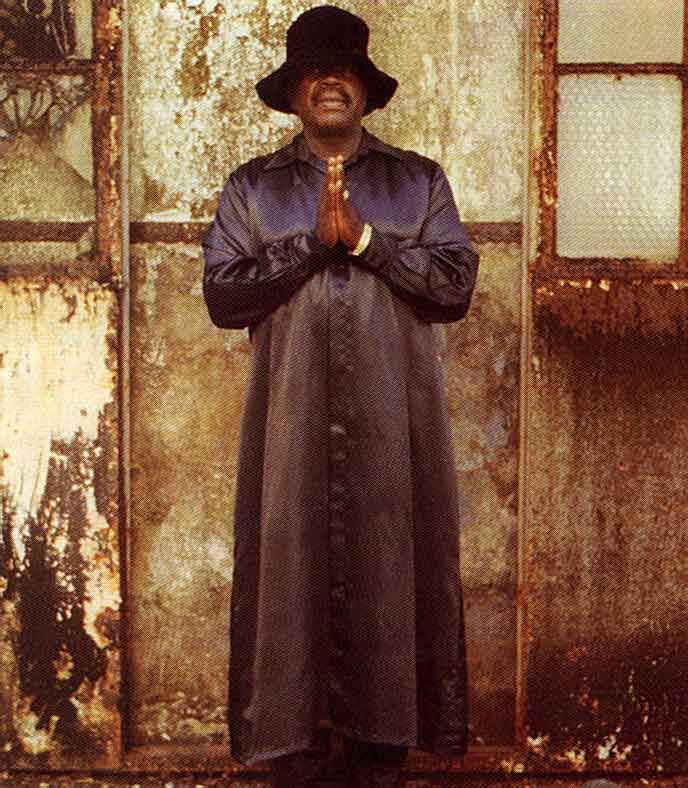

Caldwell Taylor, [Caribbean/Grenadian Diplomat (1979-1983), Historian and prolific commentator on the Calypso.

To be sure, Shadow is no elephant in the room but a Giant both of a man and of intellect who, as the epigram which frames this article suggests, ‘cast[s] a long shadow” Little wonder then, Shadow has been heralded as “The ‘William Blake’ of Calypso” (Bukka Rennie); rendered “The Robert Johnson of Calypso” (Caldwell Taylor); revealed as “A Babe in Nature’s Cradle” (Lawrence Waldron); imagined as “more primal artist than a mere calypsonian… a poet in the way Homer was” (Kim Johnson, personal communication 7/28/2008); celebrated as “Our Conscience”, Roger Toussaint And, as the other tinkerer, I’d like to build on these ‘partial truths’ by inserting my own incomplete take on the essence of Shadow’s philosophy/philosophical outpouring hopefully to help enlarge our understanding of Shadow and our own self-understanding Shadow, Himself, like a spirit in the night from the great beyond, enters and participates in — what Selwyn Cudjoe (in V.S. Naipaul: A Materialist Reading) refers to as, “the battle of readings that take place in any analysis” of a text, and declares — “I am jumbie/ come back from the cemetery?… All I know about me is I am me.” (“My Vibes are Heavy”) and fuels more tension in this virtual battle of interpretation.

Shadow’s Philosophy

Although I could find no explicit reference to ‘philosophy’ in Shadow’s legacy, at his core he was/is a philosopher bar none, and this lack of naming/defining what he does positions him firmly in the tradition of those who saw philosophy ‘not as an academic discipline but as a way of life’ Pared down to its essential element, then, philosophy can be viewed simply as the study of knowledge or thinking about thinking (metacognition) and the search for answers to ‘life and its problems” (“My Belief”) As such, in Earl McKenzie’s alluring title, ‘The Loneliness of a Caribbean Philosopher’–which can also characterize Shadow’s dilemma as he relates “I am lonely as someone/who is put into prison and forgotten” (Shadow,” Lonely Man”)–philosophy is “a natural human activity” of inquiry in which we all engage and which is not restricted to the formal university setting but can develop within ‘the university without walls’ or under an oak, even mango, tree And again in Philosophy in the West Indian Novel, McKenzie posits “philosophy [as] reflection on the deepest questions we can ask about ourselves and our world.”

Shadow’s forte, however, is not just his way of asking questions but that the effort of his thinking is justified not by the ‘finding’ but by the seeking. In “Mother Wisdom,” he signs, “Mother Wisdom said to me one day/ of all the things that comprise the world/which is the greatest of all?” thus inciting listeners to ponder the depths of that which may be unfathomable Yet, his discerning audience joins in the journey of self-affirmation to self-knowledge and beyond.

Moreover, Shadow, as a dialectical thinker, never shied away from probing any of the vexing issues—war and peace, ‘picking sense from nonsense’, the seen and unseen, profligacy and poverty, Obeah vs non-African religions, Conscience and its nullification, life and its antithesis, the false conceit of beauty and its negation, the ethical life and its absence, et al—and had a way of asking questions intended not merely at seeking answers but to finding meaning in the seeking by inviting fellow travelers to join in the journey not only of answering questions but in questioning answers, as in “Story of Life” Interestingly, in this paper, when one believes the puzzle is solved, Shadow–our Sage who “use[s] the gift of wisdom for the ethical benefit of his… community”–(“Sage Philosophy”, Kalumba, 2006)– questions what seemed to have been settled in the previous verse As such he extends Valentino’s memorable line, “I cannot agree with my own chorus” (“Dis Place Nice”) to not agreeing with an entire verse!

And in “Deceiving,” Shadow engages in an internal—even meta-dialogue “…He was born with his features/so don’t give no horrors/Just take it light/The man ain’t ugly for spite.” So Shadow is not just engaged in what Paget Henry (Caliban’s Reason: Introducing Afro-Caribbean Philosophy) calls ‘implicit philosophizing’ but in deep critical meditation on moral and ethical dilemmas that many shy away from confronting. In a Gramscian sense, Shadow may have been questioning our “conceptions of the world” by not being a mere receptacle of traditional intellectuals ‘values’ and received ‘wisdom.’

“School Under The Sky!”

In this paper, we draw on Emily Greenwood’s notion of ‘frail connections’ (in uncovering dialogues between Caribbean literature and the literature of Greece) by exploring tenuous connections between Shadow’s illuminating work and Greek philosophy, with particular reference to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave We also engage McKenzie’s challenge that we excavate “the philosophical thought which is embedded in the various forms of discourse in the region” of our hitherto unheralded philosophers–who did their “living and working in the Caribbean” As such, we tease out deep links between a trio of Caribbean writers; E.M. Roach, V.S. Naipaul, Derek Walcott; and the progressive stream of the Caribsphere soundscape against the backdrop of Shadow’s records and interviews while exploring his fascination with jumbies–a recurring stream in his songbook.

Selwyn Cudjoe’s “CLR James and the Trinidad & Tobago Intellectual Tradition, or, Not Learning Shakespeare Under a Mango Tree” is instructive here. In outlining the importance of an intellectual tradition in informing and partially ‘guiding’ the next generation, Cudjoe noted that our “exemplary talents didn’t drop from the sky, full-grown, nor [did] they learn their Shakespeare … as they lay beneath a mango tree,” but from probing the imposed canon and creatively critiquing and adapting it to our space This clash of civilizations forged something transcendental that was bequeathed to future generations, of which Shadow may have been only a ‘recalcitrant minority’ And, it is the apparent disengagement with the classics, what Rondel Benjamin, in a lecture hosted by the T&T Carnival Institute on March 21, 2019 “Walk on Dem: Lecture and Demonstration on the Stick Fighter,” describes as “internal knowledge that one discovers,” which may have illuminated and underpinned Shadow’s vision/life work.

Though a distant recipient of the education tradition and not burdened with too much formal (mis)education, Shadow has helped us understand our collective selfhood and position in the universe. As he relates in “Jump Judges, Jump,” “But when I break biche/ Myself I would teach,” suggesting an early mistrust of traditional schooling as reflected in renowned critical educator Joe Kincheloe’s assertion, “I don’t trust schools” (2004.) Suppose Shadow’s self-teaching and distancing from inauthentic pedagogy were crucial to finding his voice: In that case, he may well have been–from beyond the margins of the classroom–problematizing E.M. Roach’s revelation, “Although Cambridge school-certified, we left school knowing absolutely nothing of ourselves, our country, its history, and circumstance were… ‘exoticized natives’ my independent luck was that I loved to read…” Roach concludes, “This self-acquired knowledge of my own time, place, and circumstance turned me around,” Shadow’s independent research pondering while breaking biche was impactful. (in Michael Anthony (Ed), David Frost Introduces Trinidad and Tobago.

Perhaps this critique of formal (mis)education received its best treatment in Sparrow’s “Dan is the Man (in the Van)” with the oft-quoted stanza, “You see meh head was duncy and up to now I can’t read… If me head was bright, I woulda been a damn fool!” In a slightly different context, this enigmatic proposition approximates what Derek Walcott refers to as a “knot of paradoxes” about leaving school.

Thus, by breaking biche, Shadow underscored opposition to being a conscript of education and an Obedient Boy of the Empire. Indeed, Shadow’s flight from school further dramatized the irony of Sparrow’s verse and may well have provided grist for Lloyd Best’s timeless observation, “[T]he true casualties of our education—of the schooling which is so central—may not be the poor dropouts but the distinguished successes” (Trinidad & Tobago Review, June 1998.)

Reflecting on his evolution, Shadow noted:

“I have spent a lot of time studying but not in a formal way because what I do and what I have studied does not always happen in school. I cannot explain my school days to people. They would not understand it because there is a school out there under the sky. I went to school, but what I call the ‘real’ schooling was when I started to study Calypso just as someone who attended a college or university.” (Rudolph Ottley, Calypsonians: From Then to Now).

Shadow’s road to emancipatory education echoes CLR James’ revelations in an interview with Stuart Hall: “I paid little attention to what they taught me in school, but I plunged headforemost into the organization of society outside.” Thus, Shadow, like Socrates and CLR, underscores that ‘daily life allows us to do philosophy’ and, as such, ‘de-acadamatizes theory’ and knowledge acquisition and instead locates it in nature–under the sky. Thus, Shadow, the autodidact, though unique in his way and having a “peculiar essence”–in that while somewhat different from his predecessors–he nevertheless demonstrates fidelity and awareness not just of “the pastness of the past, but of its presence” (T.S. Elliot, ‘Tradition and Individual Talent’).

Signifying an intuitive understanding of Elliot’s insight, Shadow reveals: “At one time in my life I was fanatical over Sparrow then Blakie… I like Spoiler, and up to now, if I am passing and I hear a calypso by Spoiler, I must listen to it… [He] really used to play with our minds.” Shadow’s understanding of how the past reflects on the present and our presence is evident in the Sage’s work. It is well articulated in Waldron’s “Shadow in the Mirror: Shadow, the Mighty Spoiler and the Uncanny” Shadow, then, embraces Calypso’s glorious tradition, in Stuart Hall’s terms, as “the repository of … distilled popular knowledge and wisdom.” It is little wonder that Shadow’s discography or “Collected Works” underscores his divining the present and future in the presence of the past while generating a space to ‘refashion futures’ by laying tracks for posterity and our regeneration.

NB: This is an extended version of a paper presented at the ‘Philosophizing Shadow Symposium’ at the Lloyd Best Institute of the Caribbean (Tunapuna, Trinidad) on March 22, 2019.

NB: The author thanks Kim Johnson, Caldwell Taylor, Rawle Gibbons, and Lennel George for critical commentary on an earlier version of this paper.

Pingback: Welcome to BDN’s Post-Emancipation Issue: “Not Black Socrates, But Shadow (Winston Bailey) Learning Under An Oak Tree” | Big Drum Nation

What a wonderfully thorough and “fanatic” homage to Shadow by Winthrop Holder!

Everybody loves the music and Holder’s backstory brings even greater depth to the art.

Please publish more of Winthrop Holder’s work.

Thank you, Carlyle Leach. We are happy to have Mr. Holder’s work featured on Big Drum Nation. This is part I of a series to be published on BDN. Thanks for your response.