|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 9 mins

August 06, 2019

BDN Introduction

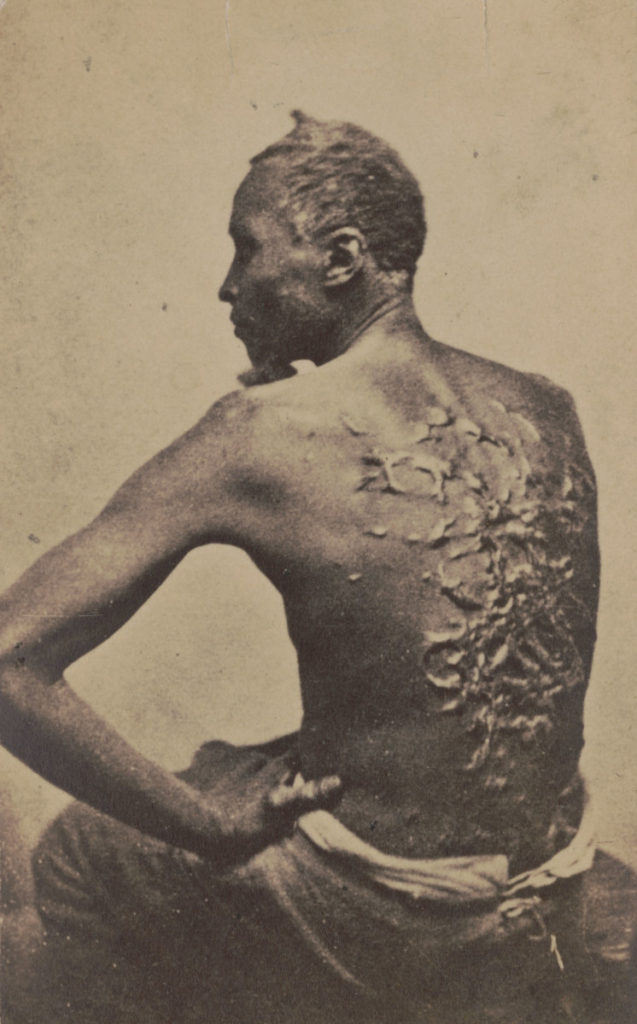

When I first came across the photograph of the slave it felt white-hot with

Photographs of suffering and oppression are commonplace, have been for a long time. Dachau, Tennessee, Biafra, Hanoi, Bangladesh, right down to today-Rwanda, Bosnia, Ethiopia. Despite the

And then there are those which pierce you, personally, in your heart.

Susan Sontag, the Jewish-American writer, describes this. “One’s first encounter with the photographic inventory of ultimate horror is a kind of revelation, the prototypically modern revelation: a negative epiphany,” she says in her collection of essays On Photography. “For me, it was photographs of Bergen-Belson and Dachau which I came across by chance in a bookstore in Santa Monica

On the Holocaust Monument in Israel, dedicated to the victims of the Nazis, is the inscription: “This must never happen again.”

We in the Caribbean have been more ambivalent towards the horror and shame that was plantation slavery. The sons and daughters of both slaves and slave-owners must live

Memory can transport you through time. A fleeting glance at the photograph pulls me back into an earlier incomprehension. Adult explanations, resolutions, theories, all the understanding I’ve dearly earned over the years, scatter like a flock of little birds.

I become a little boy sitting in a darkened cinema with my brother Lee, who is seven years older. Showing is

“I eh taking you theatre again if you going to behave so stupid, eh,” says Lee.

Fast forward. Many years later in UWI, Jamaica, I am obliged to attend

lectures in West Indian history. The lecturer, a Canadian

“There was no ingenuity that fear or a depraved imagination could devise which has not been employed… irons on the hands and feet, blocks of wood that the slaves had to drag behind them wherever they went, the tin-plate mask designed to prevent the

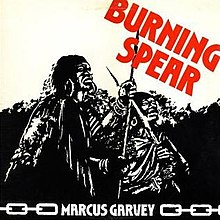

Later in the year Burning Spear gave a concert on campus. He sang the hit from his latest album, Garvey’s Ghost, which was on the radio as often as Bob Marley’s Natty Dread. “Do you remember the days of slavery?” he chanted in a voice as ancient as the Blue Mountains and which still echoes in my heart today: “Try to remember the days of slavery.” It is a memory that changes over time and, according to UWI Professor of History Barry Higman, finds “its most complete expression in the celebration of the anniversary of emancipation.”

On July 31,

end slavery at midnight in a year’s time. The date had been determined by

Jamaican slave owners, because August 1 was the formal end of the sugar crop in Jamaica. After

As a

by the older Crop Over festivities at which whites danced reels and country

dances with slave girls and Africans danced to the goombay drum. So the white upper classes took a leading role in the 1838 Emancipation Day celebrations, especially those whites in dissenting churches, in Jamaica. The Lord Bishop exhorted the ex-slaves to “

Trinidad was different. After the period of “apprenticeship” ended in 1938

the Trinidad Auxiliary Anti-Slavery Society (Tass) held public dinners almost every August 1 for two decades.

Tass was comprised of ambitious men,

stressed their identity with the ex-slaves, however, and their August 1 dinners were occasions for political speeches attacking government policies. Consequently, they were vilified by the conservative press for being “hot-headed demagogues”, “itinerant pedagogues”, “vile-tempered fanatics”.

“Let the emancipated rejoice by all means and celebrate the anniversary

of their

Two years later an anonymous policeman wrote to the paper remembering the days of slavery. “The

Baptist churches

overall the ex-slaves of Trinidad, unlike those in Tobago, remained unimpressed. For them, Carnival and its Canboulay procession were the true

“African slavery played a major role in Trinidad for a very short period, effectively 50 years…perhaps the briefest experience of African slavery of any plantation colony in the New World,” suggests UWI historian Bridget Brereton in explanation. Besides, there were many Africans here who didn’t consider themselves “fuss

As for the whites, they sat silently hoping that slavery-and perhaps

Emancipation-would soon

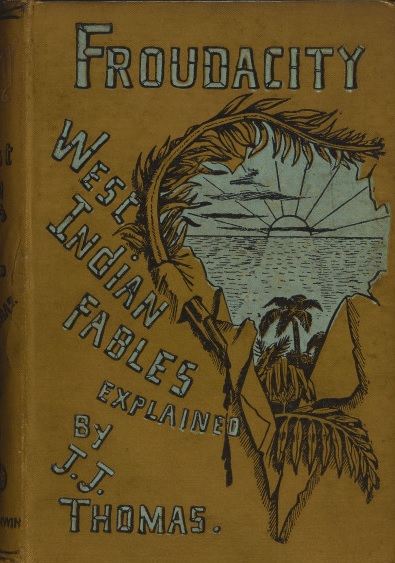

In the 1880s politics intervened again. The constitutional Reform Movement, the activities of radical Chief Justice John Gorrie, JJ Thomas’ polemics with English writers Thomas Carlysle and Anthony Froude, all served to

The young radicals

As ever the poor and the black, at least in Port of Spain, stayed away.

Outside, however, in San Fernando, Arima, Arouca, Chatham, Couva, California, Tortuga, Mayo, they marked the day with drumming and dancing in the streets. In Mayaro an 80-year-old woman recalled the days of slavery.

Thereafter the commemoration of slavery’s demise languished in Trinidad

(in Tobago it persisted long after) as the young

Like the 1880s the 1930s were a time of economic depression and cultural and political resurgence. Significantly, it was largely through the lobbying of an Afro-Chinese cultural and social activist, Patrick Jones the pyrotechnist, who sang calypsoes under the sobriquet of Chinee Patrick, that the memory of slavery was revived and a holiday granted on August 1, 1933.

But it wasn’t the centenary of the partial emancipation of the slaves (1834)

or their full emancipation (1838) but of the Abolition Act which was passed in 1833, and of the death of William Wilberforce which took place in the same month, both of which were celebrated in Britain, according to historian Seymor Drescher, “as an imperial triumph in behalf of humanity”.

Even so, Trinidadians were ambivalent. Fireworks were

Discovery Day and an essay competition held on the life of Wilberforce. One

store advertised Discovery Day Bargains (a neat ladies’ dark brown shoe with medium heels-$1.50), while the Trinidad Electric Company offered to let “peace, contentment and freedom reign in the home when you use electrical appliances” (the new turbo-vaporizer rids you of your cold overnight).

The churches got into the act too. On Sunday 23 in La

The Anglican Vicar General EJ Holt in the Trinity Cathedral noted that “the

(anti-slavery) movement revived the rich idea of a Catholic Church even though they, the originators narrowed down the meaning of catholicity.” Besides, he continued, “(under slavery) many women, children

Unlike the jubilee, however, the centenary attracted the masses because it

was promoted as a Carnival. From morning bands paraded the streets and mas and calypso competitions were held before 10,000 spectators at the Oval. Atilla, Lion, Beginner, Radio, Executor and other bards mounted a three-act Emancipation Drama.

bell and calling down fire and brimstone for the Carnivalesque desecration of the day. And just before noon, the rains came.

For three hours the city was flooded. The St Ann’s River burst its banks

and swept away houses and their contents from Belmont down. Harpe Place to Nelson Street was hit especially hard. From St James to the Oval was almost waist-deep. It was the worst flood in living memory. Hundreds lost homes and all their belongings, and 58 were compensated sums ranging from one to ten dollars.

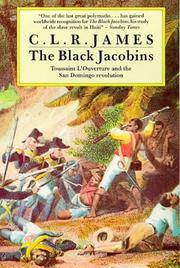

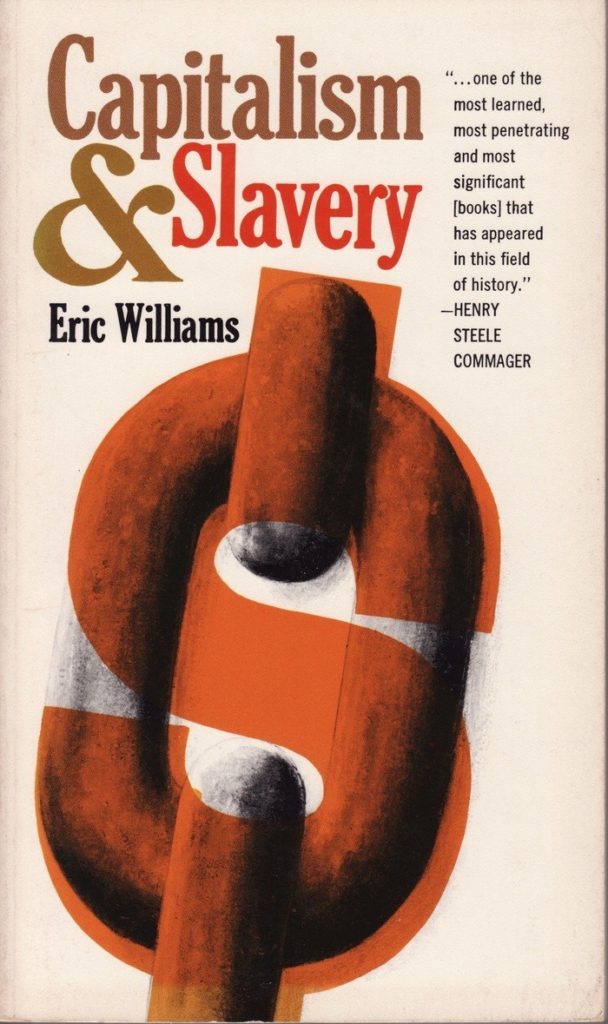

Thereafter Emancipation Day was forgotten for another half-century, during which CLR James and Eric Williams reinterpreted the history of slavery and emancipation in The Black Jacobins and Capitalism and Slavery respectively. James was awarded a doctorate in Hull, Wilberforce’s hometown, in 1983, and William’s book was the subject of a conference in 1984. Two years later the government of Trinidad and Tobago declared August 1 a public holiday to mark the abolition of slavery.

Kim Johnson is currently the Director of the Carnival Institute of Trinidad and