|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 7 mins

February 24, 2019

“I went away, I leave, and I come back home, I come back to stay.”

Andre Tanker, “Back Home’, 1974

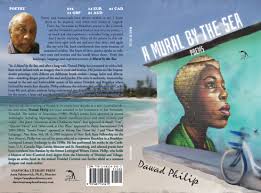

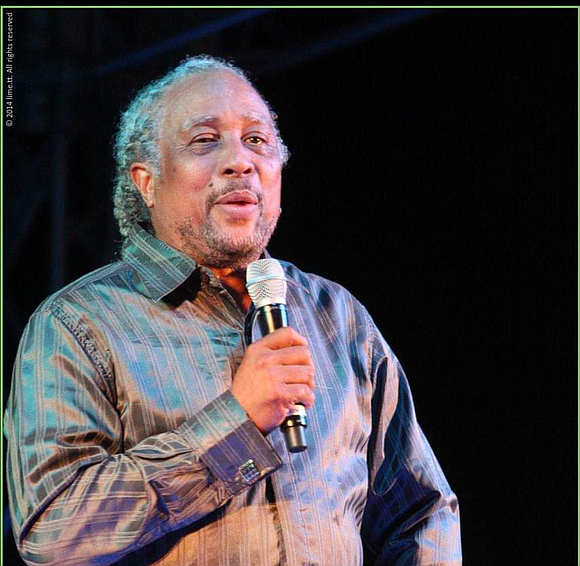

“You should never leave home if you wasn’t comin’ America to make yuhself better.” Dawad Philip, “Invocations” 1979

The epigraph that frames this review underscores the challenge that most immigrants face: How to navigate a space for self and the larger band of fellow migrants in the not-always-friendly new setting. Little wonder, then, that from very early on in his sojourn in America, Dawad Philip began

organizing and making a difference (as featured in the NY Times on August 25, 1975, merely five years after his entry into the American crucible) by orchestrating a friendlier dance/engagement first and foremost amongst Caribbean people/artists and later within the Black Diaspora and the wider society.

From early his was a mission of discerning and affirming our Caribbean essence while simultaneously breaking down barriers that may have existed within the larger Black World and beyond. And this, a life-long pledge, comes to fruition in his latest offering, “A Mural By The Sea”, wherein Philip interrogates his memory to map the spaces he has traversed. For him, then, the ‘local’ is real and, thus, universal.

Indeed, reading through this riveting collection of poems, one can’t help but discern echoes of the distinctive riddims of Andre Tanker’s “Back Home” woven between and around Philip’s lyric poems. For in Tanker’s stanzas, we hear the yearnings for home of the Trinbagonian ex-pat. This desire may not necessarily have arisen from the legend that those who eat the cascadura must return home but perhaps more from, in Sir Derek Walcott’s intimations in “Hic Jacket,” “…something rooted, unwritten/ that gave us its benediction” and thus its deeply ingrained memories of the scenic landscape and expansive vibes of extraordinarily everyday people to whom many of the poems are dedicated. In many respects, Philip’s collection is a homage not only to our elusive “Sweet Trinidad” but to the many homes and people he encountered in his pilgrimage thru life, even if temporarily fleeting ones—Russia, Brooklyn, Grenada, etc.–all subsumed under the umbrella of his enduring San Fernando, which orchestrates the collection.

Drawing on his mas-making and costume-designing playbook and his immersion in the calypso, he presents the work in four sections/verses wherein though each shard can stand on its own, there’s coherence and interconnectedness of the pieces, making the collection an effortless and remarkable presentation as one of his winning mas bands in San Fernando Carnival. The opening elegy, “A Mural By The Sea,” is a visual poem that captures his mapping of Trinidad before industrialization (by invitation) in original and electric verse. From its opening stanza, “The cocks are crowing from end to end [to] Leo the jab is standing predominate among the shoes,” one gets the sense that one isn’t merely reading lines but is being compelled to construct a picture from the words. In that sense, then, lyrics are being employed to release the imagination, thus transporting fellow travelers thru time to visualize with the poet what he witnessed and now mines from memory. And here again, in a picturesque description, we are one with the poetic eye/vision:

A horsewhip slithers through the grasslands

Of Vistabella through Marabella, making its way

past the silver domes of Point-a-Pierre, lush

acres of canefields stretching across Central,

yellow Caribs smoking leaves under the Arima Dial,

a herdsboy and his mud-caked bulls at Aranguez,

the blackened corridors of Old South Quay Station[…]

A flaming cane-arrow pierces an ox-pecker cloud,

Curls to ash like swamp-grass to a sadhu’s prayer.

In evoking a panoramic view, the poet does not merely document the multicultural landscape and people who reside in his memory but historicize every nook and cranny of his early years. And in that respect, he may be calling attention to the need to re-image and map the scenery before ‘modernity’ invaded (and corrupted the land). Philip also displays an inward-outward gaze.

Beginning “Émigré” with a scene that plays out in many metropolitan hospitals in the ‘West’, Philip asserts:

Everyone on this shift is foreign,

Every bed a story, the newborns

in their incubators hollering

at the top of their lungs…

near the door that divides

recreation from pediatrics,

an old Jewish lady who has kept

generations of buttons in a bag,

and her scissors just as long

and just as sharp.

And in this prescient poem, Philip very adroitly extends his focus to problematize world immigration, especially at a time of galloping xenophobia in the bastion of ‘democracy’ and ‘human rights.’ Reflecting on how small the world has become, readers witness…

…a boy who left Belmont

and got off a train in Lausanne

without a soul or a smile

to greet him… [and]

men who stowed away

without so much as a clue

or a care where

the vessel was headed,

anyplace but here…

“Émigré” is particularly timely and poignant, especially at this historical juncture, when though the US continues to reap havoc from its hegemonistic policies, one can’t help but wonder if the tables have turned and its mantra–to which it only paid lip service–is no longer “give me your

poor, your tired bodies” but “anyplace but here,” primarily when related to children of a specific hue.

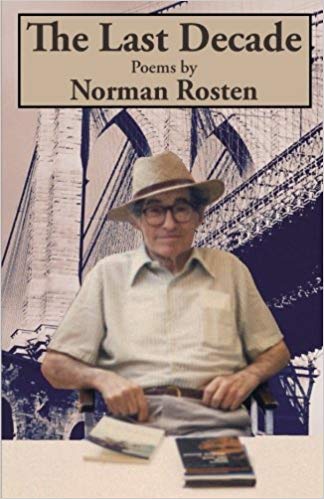

“The Hotel Leningrad”–dedicated to Norman Rosten, a one-time Brooklyn poet laureate and fellow traveler—provides glimpses of Philip’s Russian visit and captures some of the opulence while subtly alluding to the historical, social tensions/antagonisms:

Here is the Hermitage, Norm,

in all its grand extremities, marble and granite,

mosaics, stained glass,

precious metals and stones,

a world of artifacts,

serfs upon whose backs

such dynasties were built.”

Reflecting on the artistic wonders of Russia, he also reminds us, “In this place, poetry is life,

And Russia’s enlightenment

in the verses of Black Pushkin.

In highlighting the historical movement of people and ideas, “Émigré” helps situate a revelation in “The Hotel Leningrad” that…

“At the circus they sang

a calypso: Shame and Scandal,

In Russian, no less,

Woe is me…indeed!”– Makes one wonder if someone had left Sando and got off a train with Lenin in Petrograd!

Sometimes the poet engages a vexing and complex issue and reduces it to its essential core, then crafts a story that speaks to our common humanity, as in “Quarter Moon” with, “For who knows how long/ this litany will, even more, be recited…” as he ponders the tragedy that was 911. A sensitivity that opens up the tragedy to real dialogue in the way that Rudder’s “Hoosay” was a prompt for dialogue, reflection, self-discovery, and growth.

their story.

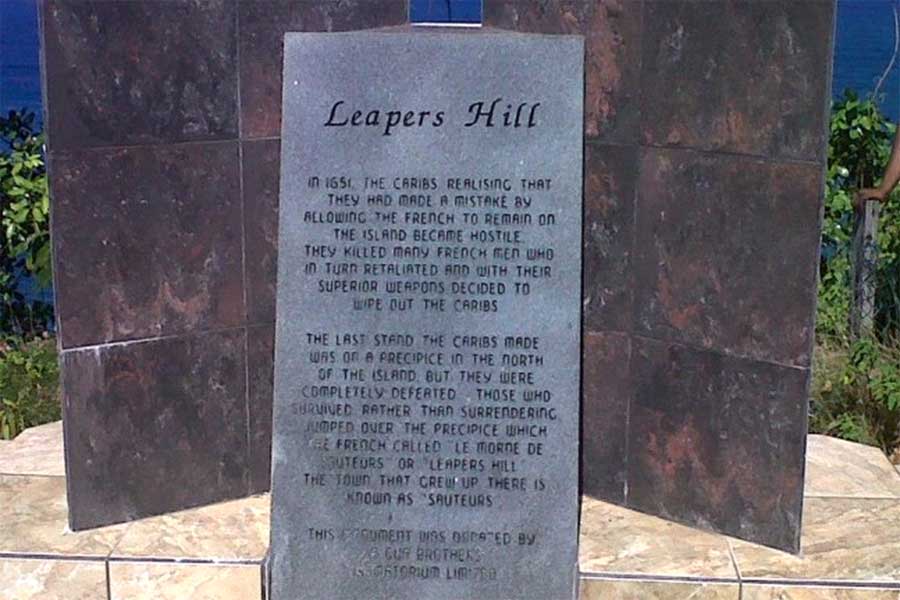

Yet, there’s a kinda harmonic dissonance in “After Work At Our Place, (St. Georges Grenada)” which begins as an ode to friends meeting after work to play music but the limerick transmutes to pay homage to the site…

…a bed of Carib bones, a sacrament

to Leaper’s Hill where the stubborn

jumped to martyrdom’s calypso,

down a path of dried nutmeg, shy egrets

festering on ticks…

And with deft notes, the poet signifies lore and arches back to end with,

…and the waves

at Grand Anse will sing

a chorus sweet as oildown,

dark as island history.

Here in quick sharp strokes, Philip reminds us how our landscape is littered with memorials-some yet to be realized—that shaped and continue to inform so much of our being. And, as if rewinding and remixing “After Work…” he upends history brilliantly in “The Conquistador’s Letter” by valorizing voices and the experiences that have been silenced for too long in the historical registers!

Part of the simple beauty of the collection is the reverence for elders and other influences on his life displayed in the benedictions. As in “Old Wrightson Road’ where we meet fellas

fresh on the scene

with talent and dream,

boys from the orphanage…

with their wands

wrote their names

boldly across the sky…[and]

made a way

in this world.

This poem, dedicated to master musician Errol Ince also acknowledges the band of pioneering musicians–and the fabled institution which nurtured them, such as Roy Cape who led the band at Philip’s D Big Apple Calypso Review–will sing thru time as a significant marker of our cultural genealogy.

Philip opens a window on many people—aunts and uncles, mas-makers, custodians of family and village lore, peddlers, panists, grassroots philosophers and, samplin’ Chalkie, ‘writes them down in history as with:

Everybody remembers Clemmy George

who kept the word and the world

in a cardboard folder under his arm.

Indeed, just as Clemmy George memorialized great titans such as Destroyer, Growler, and the Mighty Spoiler in his “Stories Of The Calypso,” presented at the 1986 UWI Seminar On The Calypso, so too Philip, in this collection, enshrines George and many other bearers of humanity’s flame. This act of remembrance bespeaks the poet’s humanistic impulse, and it’s that deep love and appreciation of people in their everyday settings-at the panyard, a wake, the marketplace, the barber and seamstress shop, etc.– which seeps thru and enriches this work and makes it stand out as a cherished possession for the ages.

Indeed, throughout this open text Philip, the masman, journalist, painter, calypso ten manager, organizer of Caribbean Theatre Week (NY), and yes, poet, manages to encase reflections of these multiple facets under one cover seamlessly and, despite the losses and the ups and downs of life, continues to resonate hope as in, “Caledonia”…

When dog-eared hymnals

render weary comfort

and Minshall’s Man Crab shifts slight

a dark curtain in the lair of the swamp,

all we could do is untangle

ourselves from the twisted

roots of despair and rave,

rave for Caledonia,

Caledonia AIA.

The poet’s bittersweet lyrics, reminiscent of an arranger’s deft chromatic run, demonstrate great sensitivity to our national pain yet do not condemn areas of darkness…

Where the mighty Desperadoes

have fled the majesty of High Cs

and the lording hills of Laventille

to an encampment

on the B flat of The Square

where the twisted roads

of Morvant must

each day give way

to flash flood of tears…

Instead, Philip reminds us that hope springs eternal through pan, sports, the lime, mas, kaiso, chutney, and so much else of our essence. Further, it’s as if in dedicating “Sando Proper” to Black Stalin, the poet also re-affirms The Black Man’s anthem, “We Could Make It If We Try”.

Winthrop R. Holder (troppy) writes when he’s “Feeling the Feeling” thru Pan, Literature, and Calypso.