|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 5 mins

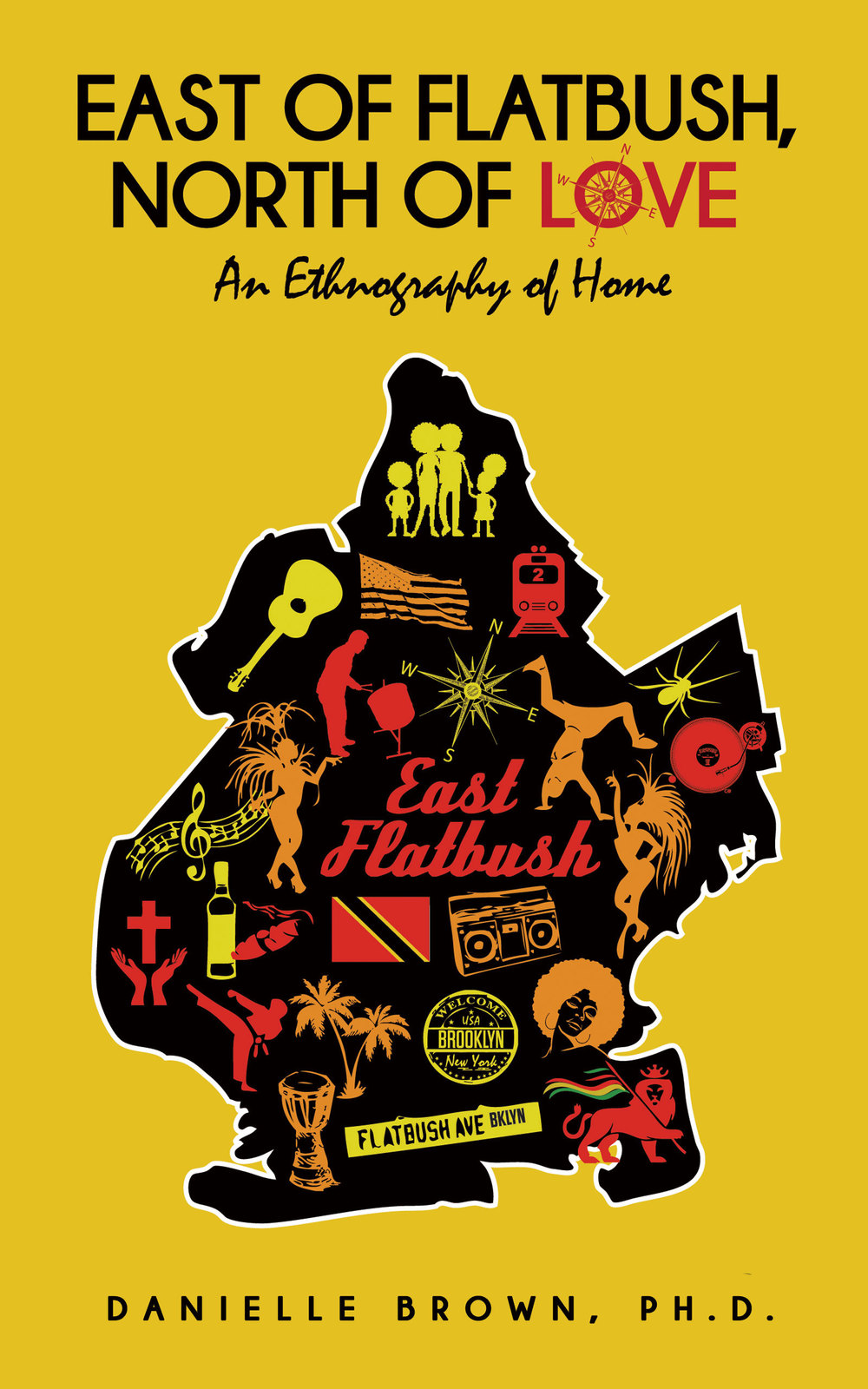

Altering the Soundscape of New York City

Author Danielle Brown reflects on Radio Station WLIB which provided the Soundtrack of her youth and more…. This extract was taken from her latest work, East of Flatbush, North of Love: An Ethnography of Home which will be featured in a Community Discussion in celebration of Caribbean American Heritage Month on Tuesday June 13, 6.00 pm @ Medgar Evers College with Roger Toussaint, former president of the Transport Workers Union Local 100, Dr. Lawrence Waldron, City College, CUNY and, the author, Dr. Danielle Brown.

Dr. Brown reflects on Radio Station WLIB which provided the Soundtrack of her youth and more. This extract was taken from her latest work, East of Flatbush, North of Love: An Ethnography of Home.

…..

“This is D. Brown rocking the mic for you. Caller, can I take your request? Hello?”

“Hello?”

“Hello. Yes. Caller, you’re on the air. Can I take your request?”

“Yes. Dis is Marcia. I want yuh tuh play ‘Ah Home’ by Iwer George, and I wanna send ah shout out to Mammy, Stacy, and Brian back home in Tunapuna. Big up TnT massive!”

“Ok. Thank you, Marcia, for calling in. Yes. Big up to all of Trinidad and Tobago and to the entire West Indian massive! Marcia, here is your request, and you know anywhere soca playin’, ‘Ah home!’”

* * *

Danielle Brown at May 14 book signing

A lot of the music that David and I listened to at home came from the radio, and Caribbean music was no different. Popular stations, like 98.7 Kiss FM, that mostly aired R&B and hip-hop dedicated some air time each week to playing Caribbean music. But perhaps the strongest radio presence for Caribbean music during my youth was WLIB 1190 AM, which specifically catered to the West Indian community. It was through this radio station that one could hear the voices of the West Indian diaspora in New York City.

Through WLIB we listened to much more than just music. In the early 2000s, I started studying the station and noting various aspects of its programming. The station aired talk shows and commercials for products and events catering to the needs of West Indians living in the city. WLIB advertised health-conscious events, such as walks for prostate cancer, as well as programs for budding entrepreneurs, like those offered by the Small Business and Development Center at Baruch College. There were frequent promotions for popular Caribbean nightclubs, like the Elite Ark, and advertisements for Travelspan, a travel agency specializing in trips to and from the West Indies. Major corporations such as Burger King, JC Penney, and First Republic Mortgage Bank sought to broaden their clientele base by advertising to a West Indian audience via the station and using (with the exception of JC Penney) persons with unequivocally West Indian accents as the speakers in their commercials.

In many ways, WLIB was crucial in crystallizing the West Indian community in New York. DJs would implicitly define the community by the music they played and the islands they would “big up” (or shout out) on the air. Musical programming played a vital role in creating bonds (or breaking them) within the West Indian community. There were times when, as a young girl, I felt that WLIB did not play enough calypso and soca, and that my heritage was being marginalized in favor of reggae and dance-hall, a sentiment that was echoed by others.

My friend Tiffany, whose father is Trinidadian and mother Honduran, once told me she used to feel slighted by WLIB’s programming:

When WLIB used to play more…specifically Jamaican music, you know…I used to be like sitting there just waiting to hear some…music from my country and it would be…one in between four reggae songs.

However, I should note that WLIB’s programming became more inclusive over the years and consisted of music not only from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados, but also St. Vincent, Grenada, and Haiti as well. WLIB even began including a program—“Indo-Caribbean Today” with Amit Parasnath—dedicated to the East Indian community, which aired every Sunday morning from eight to ten. In many ways, the station grew to reflect the changing dynamics of the West Indian community in New York City.

While the music disseminated via WLIB helped to create bonds between different members of the West Indian community in New York, there were other aspects of the station’s programming that helped to foster a sense of community. WLIB provided broadcasts to and from several West Indian countries, allowing listeners to hear live radio from their respective homelands and communicate with loved ones back “home.” Listeners who called in to the radio program were able to send greetings and messages to family members living in their country of origin. Being able to communicate with loved ones was extremely important for many listeners, as talking to loved ones via the radio offset the cost of calling home directly, which in those days had the potential to be extremely expensive.

Equally important to listeners was the ability to receive up-to-date news information from their respective home countries, as well as general news information from the West Indies. Tiffany said she liked WLIB in part because “as the day progresses, you actually get to hear international news, or news with a specifically West Indian perspective, which makes me feel a little closer to home. You know what I mean? It gives me a feeling of nostalgia.”

Together, the musical and non-musical aspects of WLIB, as well as those of several pirated stations that emerged over the years catering to the West Indian community, served to create a space where West Indians in New York could feel connected to their native lands from the privacy of their own homes. The music and information flowing from these stations contributed to altering the soundscape of New York City, bringing immigrants and first-generation Americans closer to “home.” These radio stations created an environment that allowed many West Indian immigrants to simultaneously inhabit multiple spaces. For example, West Indians who live “ah foreign” could metaphorically occupy the space of their homelands through music, despite the reality that many would never be able to return home again.

Fortunately for me, my parents had their “papers,” which meant they could leave the country freely without fear of being barred from re-entering. My father would only return to Trinidad once during my childhood, and I was almost thirty years old before we touched Trinidad soil at the same time. However, my mom made several trips to Trinidad during my youth, taking my brother and me on several of them. It was important that we learned about the land of her birth.

East of Flatbush, North of Love, is available for purchase at www.mypeopletellstories.com