|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 4 mins

We Move Tonight:

The Making of the Grenada Revolution

A Review

Fadhilika Atiba-Weza

Brunswick, New York

We Move Tonight: The Making of the Grenada Revolution

by Joseph Ewart Layne

St. George’s, Grenada: Grenada Revolution Memorial Foundation, 2014, 203 pages.

During the colonial period, the British placed tremendous significance on Grenada and made it the administrative headquarters of the group of Caribbean islands which are collectively called the Windward Islands. Independence brought its benefits and challenges, and the Spice Isle, as Grenada is fondly called had its share — foremost among its challenges was the rule of Gairy, which was a blight on the island, and an embarrassment to Caribbean people.

During the colonial period, the British placed tremendous significance on Grenada and made it the administrative headquarters of the group of Caribbean islands which are collectively called the Windward Islands. Independence brought its benefits and challenges, and the Spice Isle, as Grenada is fondly called had its share — foremost among its challenges was the rule of Gairy, which was a blight on the island, and an embarrassment to Caribbean people.

Book cover of We Move Tonight by Joseph Ewart Layne

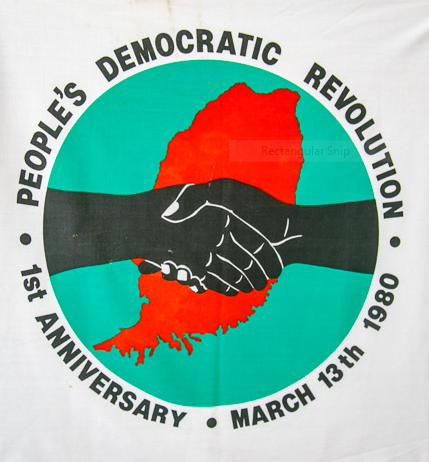

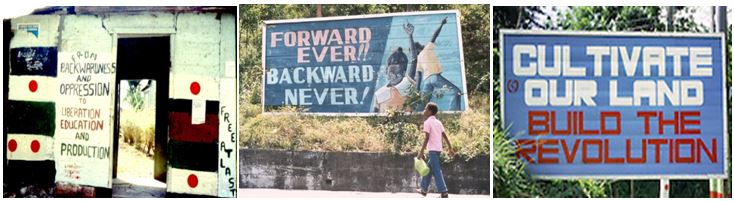

The early morning of March 13th, 1979, ushered a new dawn as the Caribbean welcomed a rebirth as the people of Grenada, led by the New Jewel Movement (NJM) removed Gairy from office and began the process of a revolutionary transformation of the country. “We Move Tonight” is the story of the developments which led to the events of March 13th. Joseph Ewart Layne, a member of the Political Bureau of the NJM, and a leader of the People’s Revolutionary Army of Grenada was a participant/observer of the process which removed Gairy and created the “Revo” as the process of social transformation was popularly called.

Layne, who was one of the Grenada 17, spent 26 years in prison following the 1983, United States-led invasion of Grenada. During that period of time, he “reflected” on the events which led to the revolution, and those which resulted in its demise. He took the opportunity to earn an LLB and an LLM, and engaged in the kind of introspection which led him to renounce the kinds of activities which resulted in some of the rash decisions that were made during the four and one half years of the Revo.

According to the author, the primary purpose of this book is to present the story of the making of the revolution so that readers can gain an insider’s perspective on the activities which led to the creation of the People’s Revolutionary Government.

Maurice Bishop on Revolution Morning

The book is organized in three sections. The first is a political autobiographical journey which begins with the author’s introduction to, and initiation into the National Liberation Army (NLA), and concludes with its triumph over Gairy’s police and paramilitary forces. Along the way we learn of the decisions which were made by the leadership of the NJM, the processes by which the decisions were made, the challenges and dangers which they faced. By identifying key players, the reader is treated to a narrative which contextualizes the decisions and activities of the NJM as the critical day arrives. We are provided with examples of the brilliance of the chief strategists of the revolution, along with some of the amateurish mistakes that could have been fatal.

It explodes the myth that the revolution was an act of desperation. We are provided with evidence of a deliberative and methodological planning process which at times frustrated the youthful and enthusiastic Layne and his peers.

The second section is a brief review of the political history of Grenada. After having read the first section, it appears that is section would have been better placed as a preceding section. Nevertheless, Layne places in a historical and political context the birth of the NJM and its predecessor organizations, the factors which influence some of the developments in the country, and the political climate in which the revolution triumphed.

The third section is most disappointing. The author briefly mentions that there was a problem in the party, but did not elaborate, nor did he address the issues which led to the problem. Given the detail with which he addresses the first section (activities leading to the attack on March 13th, 1979) one expected a similar treatment of the issues which led to the fatal day of October 19th 1983, but this a glaring omission. Given the delicate nature of this matter, and the emotions which it evokes, tremendous tact and diplomacy are required. One has to assume that there are political and legal reasons for the author’s decision to exclude this painful chapter in the history of Grenada.

In addressing the issues of October 1983, Layne states that, “When faced with a challenge to his absolute leadership of the party, PM Bishop did not go to the people with the genuine issue. Instead he issued a rumour that a plan to kill him was uncovered. The other side reacted by putting PM Bishop under house arrest. From there things catapulted out of hand.”

The above raises more questions than it has answered. What happened to the Bishop Coard Whiteman team that Layne proudly mentions in earlier part of the book? When did Bishop assume absolute leadership? How did it occur? What exactly, is absolute leadership? What kind of challenge was issued? How could the “genius of Coard” not have foreseen the consequences of such a reckless act of placing the popular PM under house arrest? There are many other issues that can be raised in light of the weakness of this section, but overall this publication is a welcome contribution to the literature on a very important development in the history of the Caribbean.

Previously published in In Motion Magazine August 26, 2014.