|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 3 mins

AL ROUGIER on OCTOBER 15, 2016

As the crows fly above, the sun re-emerges after the light drizzle that moistened the bodies of the protesting crowd. Their bodies glistening with the mixture of sweat and raindrops, and pure adrenaline .

.

At this point, Maurice is surrounded by his comrades, in the Operations Room where major decisions are being made. There is a mixture of adults and youths, young and old alike, male and female, supporters and new supporters. With this deadly cocktail of people where values and ethics differ, comes the deadly decision made by his populace who hijacked his leadership, to fight the powerful and ideological military regime. His political chairmanship has been hijacked and has taken a course that is not of his own choosing—though, a few minutes later, he will pay for their choices.

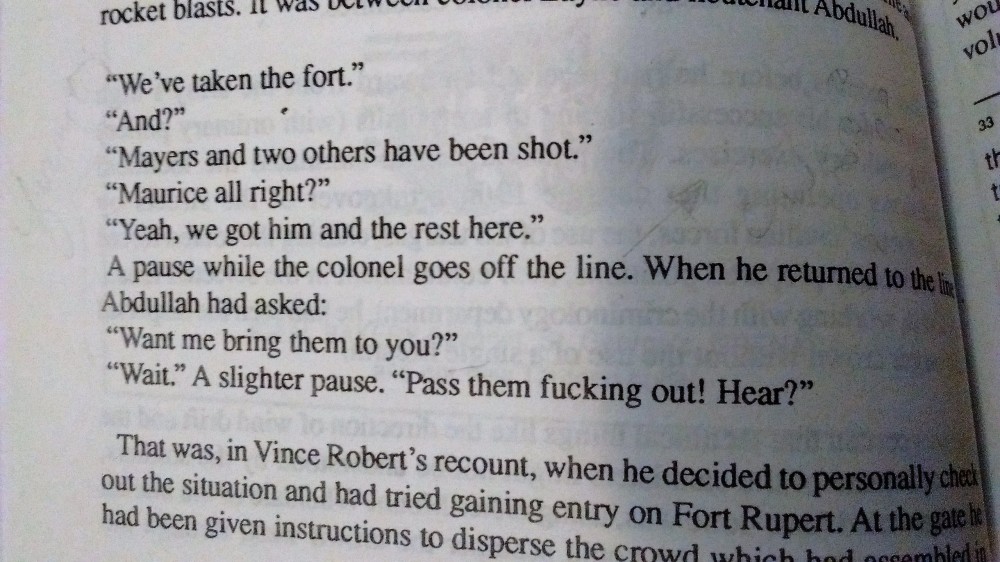

Before the volley of gunfire ruptures the chanting demonstrators on the fort, the correspondence between Fort Rupert and Fort Frederick is heating up. The desire for vengeance, power, and thirst for blood is manifesting. At this point, the intention is set and there is no turning back. He must die. It is now or never—and they chose now.

No one expected the events that followed—the lining up of Maurice and his cabinet ministers along the walls of Fort Rupert, this relic of a colonial past. Its stones hardened with blood and memory of years gone by, of lives deceased, and the effects of weather patterns and the salty air of the Caribbean Sea. It will soon be accessorized with the ricocheted bullets of highly powerful automatic rifles, blood, bone fragments, brain matter and, ruptured flesh. The volley of gunfire will now become the official soundtrack to the terror and fear of 19th October, 1983.

And just like that, the tiny tri-island state of Grenada, Carriacou and Petit Martinique has become world news. This moment will forever leave ripples and shrapnel in the lives of Grenadians near and far. To this day, the metal fragments from that day are logged in the minds, bodies, and the soul of a nation.

Long live these names: Andy Sebastian Alexander, Nelson Steele, Simon Alexander, Vince Noel and Avis Ferguson (two of the first to die), Alleyne Romain, Eric Dumont and Gemma Belmar–this list includes “students, laborers, union leaders, New Jewel Movement members” (Puri 2014: 90). The PRA members killed that day, including Dorset Peters, are: Raphael Mason, Conrad Mayers, Martin Simon, Franklyn James and Glen Nathan. The ministers lined up and killed: Jacqueline Creft, Evelyn Bullen, Fitzroy Bain, Norris Bain, Unison Whiteman, Keith Hayling, Evelyn Maitland and Maurice Bishop.

Long live these names: Andy Sebastian Alexander, Nelson Steele, Simon Alexander, Vince Noel and Avis Ferguson (two of the first to die), Alleyne Romain, Eric Dumont and Gemma Belmar–this list includes “students, laborers, union leaders, New Jewel Movement members” (Puri 2014: 90). The PRA members killed that day, including Dorset Peters, are: Raphael Mason, Conrad Mayers, Martin Simon, Franklyn James and Glen Nathan. The ministers lined up and killed: Jacqueline Creft, Evelyn Bullen, Fitzroy Bain, Norris Bain, Unison Whiteman, Keith Hayling, Evelyn Maitland and Maurice Bishop.

For the past nine years I have been carrying the memory of Fort Rupert with me. I did not live through it, I was born a month later. I actively started doing research on the events of 19th October, 1983 earlier this year with the simple hope of finding answers and closure for myself and hopefully for the grieving family members. It has been a challenge. It has been rewarding. It has been complicated. It has been frightening. It has been cathartic. As I pay homage to the lives loss on that fateful day, I bid them all farewell. I must leave them here.

InSongs of Blood and Sword, Fatima Bhutto, in describing the political climate of Pakistan and the violence that has persisted since its birth, hauntingly writes, “It has been a trial writing this book about my family. Through letters and notebooks, photographs and interviews, it has opened them up to me and made them, all my ghosts, whole. But by virtue of what I now know about them, I must close them off. I must take my leave and remove myself from their shadows, their glories, their mistakes and their violent, extraordinary lives. There is just one member I cannot leave behind, Papa. I started this book with the intention of making my peace with my father, of finally honouring my last promise to him—to tell his story—and then, to finally say goodbye. But I can’t. He especially became whole to me, flawed and ordinarily human, unlike the immortal being I revered as a child growing up. His choices, remarkable and dangerous, honourable and foolish, are not mine but I lived them. I have also lived, since his death, with an incomplete picture of my father as a murdered man—holding vigil for him daily in my thoughts, in my steps and travels, in my public moments and in my eyes blinking him in every morning and closing him off to sleep every night. I had forgotten, in these fourteen years, that he was once alive and, for a brief while, only mine. He seems very alive to me now. It is too sweet a thought to push aside, so I delay the thought of farewells, if only for a little while longer” (437). Unlike Fatima, I bid the dead farewell.